This story, “Calabogie Bass,” appeared in the August 1956 issue of Outdoor Life.

As we passed beneath the railroad bridge and into the bay that stretched before us, Bill Levan cut the motor and let the boat glide to within spin-casting range of the blooming hyacinths along the edge. His battle-scarred plug hit the quiet water, rested a moment, then quivered about a dozen times when suddenly a bass exploded from the water and cartwheeled over the surf ace.

Bill chewed his cigar nervously and hung on to the rod for dear life as the fish dashed headlong into a bed of weeds. I eased the boat toward the spot to untangle the bass and saw that it was a big moss-colored largemouth.

Within 30 minutes three more whoppers came to the net. But it hadn’t always been this easy. Before, other fishermen staying at the same lodge on Calabogie Lake were taking bass, but not us. We’d wasted two arm-aching days spinning plugs and spoons, catching only a two-pounder and a couple of rock bass. Then I found my son’s toy balloons in the tackle box, and after that it was like offering bananas to starved chimpanzees.

Bill worked long and hard to talk me into going along last August on this trip to Ontario, Canada. He operates a dry-cleaning delivery truck in Nescopeck, Pennsylvania, and one morning while delivering some cleaning to me, he said, “We got to make a trip to Calabogie. There’s plenty of bigmouth bass in the lake. If these aren’t hitting, we can try the Madawaska River for smallmouths or the 12 to 15 lakes close by that are teeming with bass, northerns, wall eyes, and some with lake trout.”

“But it’s August,” I said, “the poorest fishing month of the year.” On top of that the East was having one of its hottest dry spells ever. I’d lost all ambition and didn’t relish the thought of a 400-mile drive.

But when Bill told me that all the dry cleaners closed down the first of August and that it was then or not at all for him, I gave in. At midnight the next Saturday we were on our way.

We drove through Cortland, Syracuse, and Watertown, New York, then across the St. Lawrence River by way of the Thousand Islands Bridge. After customs, we went on to Perth, Ontario, and later, through the land of the balsam and blue spruce to Barryvale and Calabogie Lake.

It was noon when we got our first look at Calabogie. The lake stretched about three miles wide and five miles long. It was rolling and tossing from the wind — too rough for a small rowboat — so we slept until almost sundown.

Fred Clemens, the lodge owner, told us that a few big bass had been caught in Grassy Bay, also some husky channel cats running to 12 pounds. I was willing to fish for these heavyweights, but Bill wanted bass. The lake had simmered down, so we loaded the skiff and took off through Clemen’s inlet and into the open lake, heading north for Grassy Bay.

The bay, around the first bend from the lodge, is separated from the main lake by a railroad causeway built of ballast. Two openings in the causeway let water into the bay. These are each covered by low, narrow bridges over which two

small freight trains pass daily.

As we approached one of the small openings a dozen fishermen sitting on the railroad track hauled in lines to let us pass. We found later that the strong current rushing through the opening makes it ideal for smallmouths and walleyes. Once inside we found the bay chockful of weeds with wild rice, lilies, and hyacinths lining the shores.

“Let’s try casting to the shore with surface plugs,” Bill suggested. He cut the motor and we drifted to a slow stop. The sheltered bay mirrored the setting sun and the big golden moon as it slid up in the East.

“Hot weather and a full moon. We couldn’t have picked a worse time,” I said, between puffs on a pipe. The next two days proved I was almost right.

Neither Bill’s frog-colored surface lure nor my small popping plug did much of anything that first evening-with one exception. That was a whopping splash at my plug. I was ready and set the hooks hard. The fish flew out of the water, leaping, diving, and thumping the line. It turned out to be a 2½-pound smallmouth.

We hooked several rock bass and a 10-inch largemouth, then all was quiet, so we went back to the lodge. That night we learned from other fishermen that live frogs were about the only things you could pin your hopes on for getting bass.

Came morning and the air was cool and quiet, the sky flaked with small clouds. Surely today they’d hit. This time we went south past a pile of rocks known as Crab Island and into a beautiful cove called Cameron’s Bay. Dozens of log pilings were sticking a foot or so above the water, ideal for bass and northerns. But we should have stayed in bed. We didn’t catch a thing.

Next day we headed for the town of Calabogie where the water dropped off abruptly to 30 feet. As one plug failed we tried another, then turned to spinners and spoons. We scared up two small bass during the morning, so in the afternoon, we rigged spinners and trolled the river channel. Clemens told us the water there was 150 feet deep, with concentrations of big northerns, walleyes, and muskies. We couldn’t prove a thing.

After dinner we held a powwow and concluded that since Grassy Bay was the only spot which produced a good fish, we should concentrate there. So that evening we joined the parade of boats outboarding toward Grassy Bay, took our turn ducking under the railroad bridge, and headed toward the spot where I picked up the smallmouth. The wind was settling down to a whisper.

Bill snapped a battered plug to his line as I maneuvered the boat to within good spinning distance of the shore weeds. Reaching into the tackle box for the flashlight, I uncovered a package of colored balloons.

“Balloons,” I said loudly. “They must belong to my little boy, but how’d they get in here?” Come to think of it, I’d read a piece in OUTDOOR LIFE about how a guy used inflated balloons to catch bass (Ken Smith’s “The Balloon Trick” May, 1955). I’d put some in the box with the idea of trying the stunt and then forgot all about them.

Fingering the balloons for a moment, I also remembered hearing someone say he had luck using a slice of balloon fastened to a plug. I hesitated, then decided to try it.

Picking a yellow one from the envelope, I sliced it into four long strips and slit each of these part way to form wobbly legs. I pushed one strip on the rear hook of my injured minnow-type plug, then handed one to Bill.

Mumbling some skeptical words, he fastened the strip to his plug and cast it toward the hyacinths. I swear he hadn’t made much more than two turns of the reel handle when the surface boiled, causing the hyacinths to heave and toss. Although taken by surprise, Bill managed to set the hook as the bass wheeled over the surface.

“Grab the net,” Bill shouted, chewing harder on his half burned cigar. I maneuvered the boat to keep the bass from diving under the craft, and after about a 10-minute battle, the bass succumbed to the net. Grinning broadly, Bill un hooked the six-pounder.

Meanwhile I made a cast toward a rotted stump standing near a bed of wild rice. The minnow’s churning spinners made a slight purring sound as I retrieved. Halfway to the boat the plug was sucked under. I jerked the rod hard, and as the fish felt the biting steel, it broke water, then stood on its tail, shaking its head violently. It made two more leaps and practically jumped into the outstretched landing net. But, far from spent, it flopped on the boat floor and walked over my open tackle box, sending plugs flying every which way.

We caught these two bass and hooked six more — two of them keepers — in the next 20 minutes. Then the moon moved from behind a bank of dark clouds and all was quiet.

“Don’t suppose those balloons had any thing to do with it,” Bill said, “but this was the best fishing we’d had in two days. The bass would have probably hit anything tonight because they were in the mood, probably hungry from fasting.”

“Maybe,” I commented, “but I’m keeping on my balloon strips in the morning.”

That night we were the toast of the lodge. Four big bass ranging from 3½ to six pounds were the best taken out of the lake for days. We told of fastening a piece of balloon behind our plugs. I suspected the others were laughing at our stunt, but their smiles weren’t too big as they gazed at our string of husky bass.

For the next few days we enjoyed Calabogie bass fishing at its best. Early mornings and evenings we motored to Grassy Bay and spun plugs and spoons adorned with balloon strips into the wild rice and blooming hyacinths. We didn’t take bass on every cast, but we took three or four whoppers each trip, plus an assortment of youngsters and skinny northerns. We forgot the Madawaska River and the myriad lakes in the region. Grassy Bay gave us plenty of action.

When we removed the balloons or cut the tails short, we failed to get strikes. We missed two strikes in four, but still we connected and landed far more bass than the other fishermen caught on live minnows and frogs.

And we had real fun with spinning tackle, particularly when landing a scrappy five or six-pounder in dense weeds and stumps. Normally, heavy tackle is preferred, including a stout casting rod and 15 to 18-pound-test line, so heavy fish can be kept from diving into weeds or under logs. Our spinning rods had pretty stiff action and we used 10-pound test monofilament lines. Eight-pound-test probably would have been better, for our casting distance was cut substantially with the heavier line. But we were able to pull bass, weeds, and rotted limbs from the bottom when the fish dived. In fact, the spinning outfits handled plugs up to 5/8-ounce without any noticeable strain.

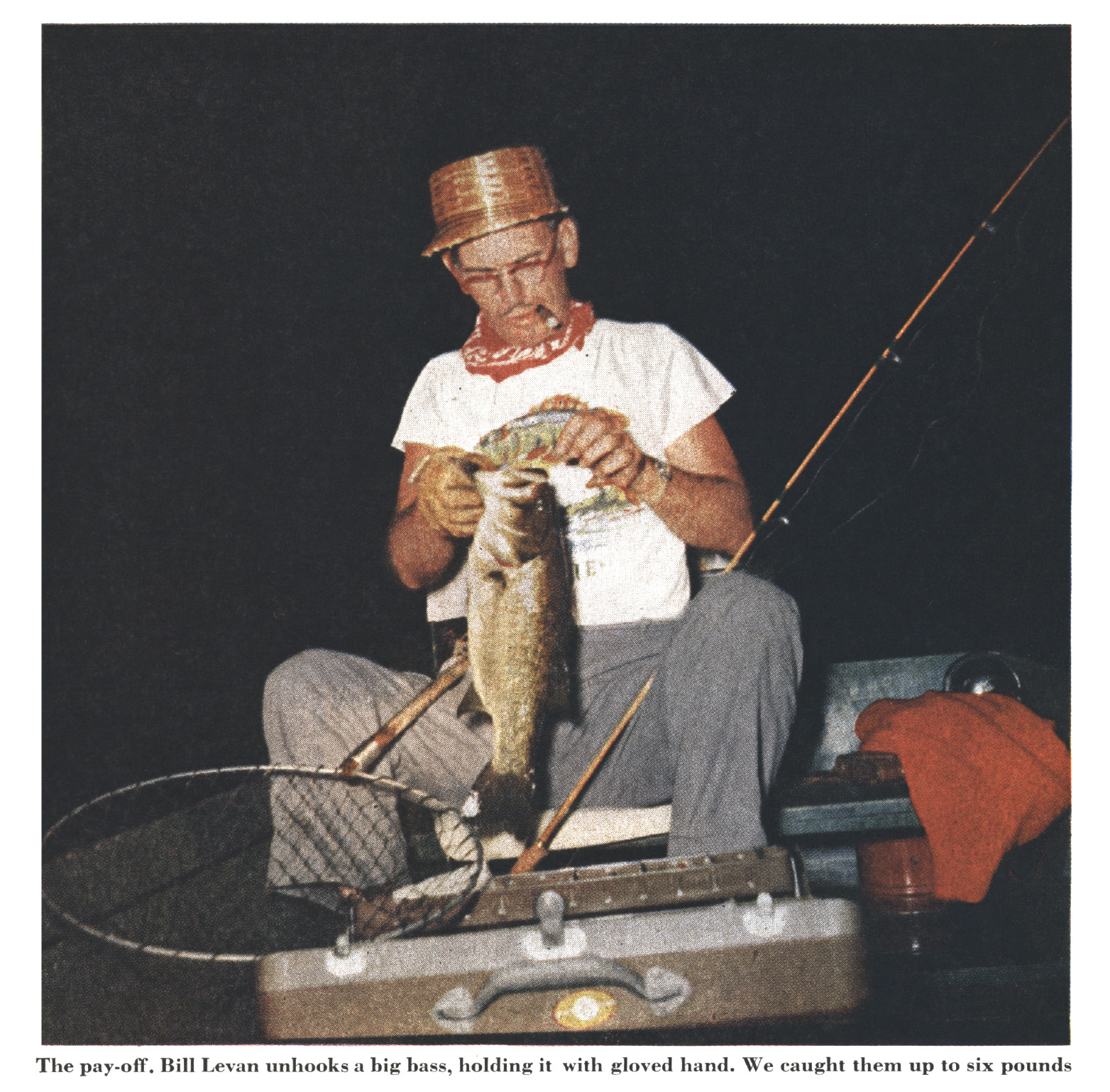

A pair of leather gloves proved to be a handy item for us. Bill once suffered two badly lacerated fingers when he tried removing a plug swallowed by a northern. This time he took a pair of lightweight work gloves along in his tackle box. After landing his first bass, he pulled on the gloves and went to work unhooking the lure. The bass harmlessly dug the hooks into the glove, but Bill’s hands were fully protected and didn’t get a scratch.

The morning following our balloon debut was spent in Grassy Bay. The wind blew quite hard, pushing us across the lake. While drifting we cast our plugs and half-reeled and half-trolled shallow-diving lures equipped with balloon ribbons. We found that the bass moved into the thickest weed beds during the day, into the shallows at sundown, and back to the depths at sunrise. Deepest water in the bay was around 15 feet, with weeds growing to within four or five feet of the surface. Whenever our plugs wiggled over an opening, a bass usually zoomed for it. About every fourth cast brought weeds to the boat. Weedless spoons picked up grass too, but we’d occasionally get a partial retrieve free of weeds and have an old socker pound it hard.

We caught a dozen bass that morning, including three more keepers. About noon, as we headed back toward the railroad tracks, we noticed water surging from the lake into the bay, boiling the surface for 20 yards. We remembered what Clemens had told us about the lake water bring ing in food and the concentrations of fish that hang out there at that time, so we anchored slightly left of the current and began spinning.

My second or third cast was grabbed by a scrappy small mouth that measured a foot. Then Bill caught one about the same size. Using small plugs with balloon streamers, we hooked better than two dozen bass within 10 minutes, none worth keeping. That afternoon we trolled in the deep channel and I snagged a fat walleye on a deep-running plug equipped with a piece of red balloon. We went back that evening to Grassy Bay and picked up four more big largemouths.

Saturday arrived far too soon, but we weren’t reluctant to return to Pennsylvania. Calabogie had given us unforgettable bass-fishing thrills. Once we added balloon skirts to the plugs we had plenty of action. I suspect this was the first time the bass there had seen a plug waving a flag. It proved to be the downfall of more than 50 of them.

Back on the road again, we retraced our tracks over the twisted, hilly road to Perth, then south to the St. Lawrence River and back into New York. As we glided through Watertown, I spied a familiar 5-10-25c sign hung across the top of a building, so I jammed on the brakes.

“Why are you stopping?” Bill asked.

“I got to get my little boy some balloons. I’m going to buy him the biggest bagful I can find.”

Read the full article here