This story, “Partners And Other Gifts,” appeared in the July 1991 issue of Outdoor Life.

A hunting partnership is a special thing. It often lies dormant due to time and distance, but these are fragile barriers. It always revives when diminishing sunlight prompts autumn’s chorus to promise yet another hunting season. This siren’s song arises from the murmur of doves on an Arizona stock tank and the rattle of Indiana cornstalks. Wherever hunters live, some version of it reaches them, setting in motion the planning, excitement and last-minute phone calls. Months, even years, evaporate as hunting partners reunite at a familiar duck blind or hay field.

Partnerships derive their vitality from the sharing. Cold days, looking for lost dogs, miles of brush-busting and campfires are certainly part of it. But the sharing is of kindred attitudes, too. It is the respect and appreciation for the game, and the courtesy to handle guns or bows safely.

Hunting partnerships are notoriously difficult for outsiders to join. The very things that work to bind also serve to bar; Men can work with, or live next to, nearly anyone, but they can be hunting partners only if their ideas about die sport, the game, and often about life, are compatible. Yet there is a soft spot in many partnerships. Every year, in every part of the country, an established hunting group will admit some hopeful kid; to give him a start, to do him a favor, to let him benefit from their expertise. This is exactly how my partner and I found ourselves with a sandy-haired 13-year-old named Ronnie in tow one long-ago September.

Mike probably knew before he called that I would agree to take the boy along, but the courtesy was extended anyway because there were pros and cons to discuss. We would have to attend to the young bowhunter’s safety in the comparatively remote area we usually hunted. Trying to educate the boy would surely be a distraction from our own hunting. We did not specifically mention that it was an opportunity to repay part of our debt to those who had fostered our first steps afield. We just decided that it wouldn’t hurt to do the kid a favor.

I was banging on Mike’s back door long before daylight that first Saturday morning. As I entered, he thrust a mug of bulletproof coffee at me and made the introduction. Ronnie waited for my reaction, his friendly face a mixture of awe, apprehension and silent apology for his youth. Remembering the feeling from long ago, I gave him a big smile, shook his hand and assured him that it would be up to us to get a deer because Mike couldn’t hit a phone booth if he were locked inside. A relieved grin swept all the way around his head. He knew he was going “real” deer hunting now, with “real” deer hunters, and the pact was made.

Blessed with a huge mast surplus that year-various acorns and other “nuts” were everywhere-we hunted every weekend in the beech and oak woods along Ohio.’s Mohican River. At first, we parked Ronnie on ridgetop stands and circled to quarter into the wind toward him from different directions. He always claimed to have seen deer, but he had never drawn his bow. We wondered if he was too fidgety until one day we arrived at his blind to hear his excited tale of watching a fox stalk and catch a ground squirrel. He showed us the scuffed area of the capture, and in some bare earth nearby were the dainty, unmistakable tracks. His escaping the notice of a fox at 30 yards for several minutes made it our turn to be awed, and pleased.

Time spent on the stands quickly gave Ronnie a general familiarity with the area. With some lessons about his compass and the aid of our marked-up topo maps, we could soon trust him to solo on stalk-and-stand ventures through the woods without getting lost. Given a chance to be a partner, instead of just a kid, Ronnie grew before our eyes. Watching this miracle of developing skill and confidence added a new dimension of reward to the season for Mike and me. The boy’s rapidly increasing abilities were as much a source of pride for us as they were for him. Outdoor lore fascinated Ronnie. He wanted to know about everything he saw. He hung on our words as though each was a precious gem. This innocent flattery was pleasant, but somewhat embarrassing for two men who were still hunting for a few answers themselves. Keeping up with his questions demanded that we spend more time investigating the area and the activities of its wildlife. Truth is, the attempt to live up to our image probably doubled our own knowledge and skill in a single season.

Ronnie’s greatest passion was learning to read deer sign. The lion’s share of this instruction fell to Mike. The tall West Virginian, though noted for an occasional dubious story, can trail a gnat through a ticker-tape parade at a dead lope. The youngster picked it up fast, and one of our grandest afternoons was the day Ronnie located a line of five scrapes strung through a large tract of second-growth. By December, the boy had made great progress. He listened well and could be relied upon to keep his bearings.

It would be fair to say that we teased Ronnie, frequently. Our threats to make him clean and carry our deer or “run on into town” (12 miles) to fetch us some hot sandwiches always amused the cheerful teen. Kindling his broad grin and clean laughter brightened even the most discouraging day.

Occasionally he would retaliate, as when we were riding home through the dark on the last day of the season. We were having a high time discussing the day’s hunting, when suddenly it occurred to Mike that it was all over, and none of us had taken a deer.

“Holy catfish!” Mike howled at Ronnie. “Hunt all year with you and come home empty-handed? Mama’s gonna wonder if maybe I haven’t been out chasing the streets instead of hunting. Boy! She’s gonna run my hide up the flagpole!”

“That’s right!” I added. “How are we going to alibi a whole three-month season and not a deer between us? We’ll be sleeping out in the snow unless you come up with something real good to tell everybody back home, boy!”

“Why me?” stammered the boy.

“Because they’ll believe you, boy!” Mike exclaimed. “You gotta learn, boy, that sometimes wives don’t always listen to the truth, no matter how you arrange it. So you’d better think of something good.”

“I don’t know about you guys,” Ronnie began with a smirk. “But I’m gonna tell ’em that I didn’t get a deer because I’m just a kid, and you two have just been dropping me off at the woods in the morning and picking me up again at dark.”

Complete failure of the mast crop caused us to change hunting areas the following year. Scouting during the squirrel season revealed that the hardwoods were receiving only random attention from the deer. We quickly began asking around for permission to hunt on the small, open farms in the area. Our chief interest was land along the larger streams, and we gained access to two farms by opening day.

With numerous food plots available, the key factor became the relatively unmolested cover along the water courses. Daily farming activity, squirrel hunters, woodcutters and the ubiquitous farm dogs rousted deer from the fields and scattered woodlots, forcing them to shuttle up and down the creek bot toms. With deer lying tight in the thickets along the streams, stalking mistakes would be easy to make. Blunders would certainly send the deer across the boundary lines, where we could not follow. This would be feast-or-famine hunting at its toughest.

The first morning, Ronnie and I still hunted along opposite banks of a creek, with perhaps 60 yards between us. Mike was in a bottomland tree stand ahead of us, near the edge of the property. We eased cautiously into the breeze, one of us moving 10 yards or so, and then halting for several minutes, while the other advanced.

About an hour had passed when I spotted the youngster standing quietly, his attention riveted on a brushy draw that led up and away from the stream to a cornfield. Within a few moments, an antlerless deer emerged, loafing along toward Ronnie, completely unalarmed. Suddenly my palms were sweating and my heart stampeding. The distance between boy and deer shrank slowly.

“Wait!” I whispered involuntarily, as if my young partner could hear me, or even knew I was on the planet. “Relax! Don’t move. Wait until it goes by. Don’t blink. Don’t sweat! Just wait!” But everything was up to Ronnie.

The deer was within 25 yards and would go by even closer. If the boy could last a few more seconds without being discovered, he should get a close shot. Ronnie was as solid as a pointer, and the deer minced steadily nearer. A dozen paces past the boy, it stopped to snack on a maple sapling. Ronnie’s left arm straightened and rose as he drew the shaft smoothly to his cheek. The deer was still feeding unaware, but the youngster relaxed his draw and lowered the bow. He watched the deer for a moment, then kicked some leaves at it to send it bounding along the creek bottom.

When we met later at Mike’s stand, Ronnie’s exhilarated account of his experience with the deer, a button buck, added a lot of pleasure to our cold cuts and candy bar lunch. We were proud of his composure under the nerve-rattling tension of having a deer almost in his lap, but the finest reward was his explanation for not shooting.

“I had that buck cold, and I wasn’t afraid to shoot, even though I was shaking a little. If I had taken my deer, though, I’d have to wait all the way until next year to go hunting again!”

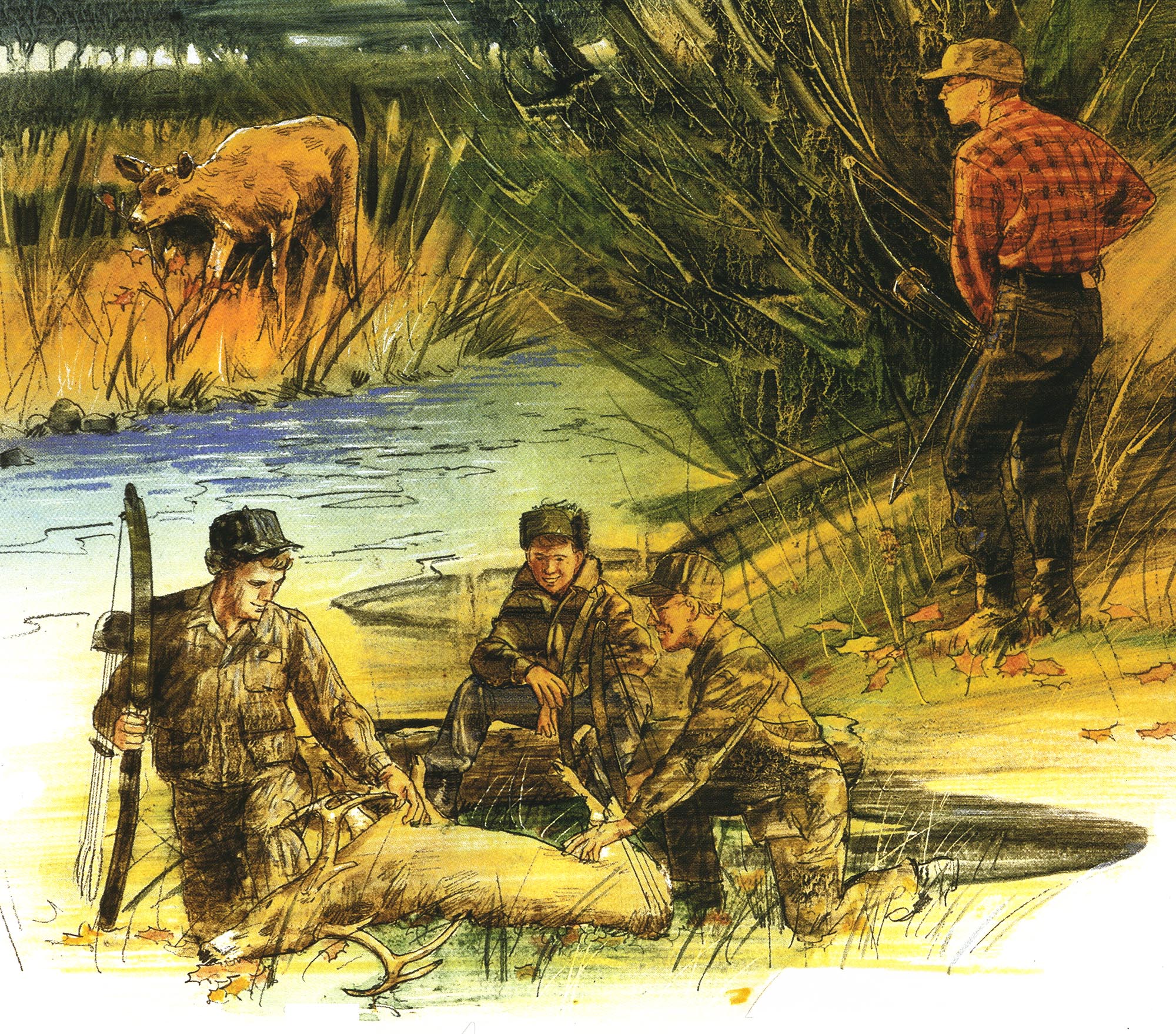

The following weekends were exercises in disappointment and frustration. There were many days when it was mostly Ronnie’s enthusiasm for the hunt that dragged us into our camo. Then, on a bright December day, Mike took a strapping eight-pointer.

There were the usual congratulations and good-natured jibes as we each found a spot to sit on our heels and admire the buck. Inevitably, the banter gave way to reverence, and the silent awe of mortality.

“He sure is beautiful,” Ronnie said in his quiet way. “I’m sure glad he didn’t get pulled down by dogs. Are you going to have him mounted, Mike?”

“You bet!” replied Mike. “This old buck is going to be with us for years to come!”

Not long after the season closed, Ronnie’s family moved to another state. We immediately campaigned to have him returned for some hunting the following season, and his parents agreed to let him come back at Thanksgiving. Regretting his location, but taking solace in the promise of a November reunion, we bid our young partner a temporary farewell.

But in one inexplicable moment an auto accident made this already indifferent world a little colder, and a lot poorer. It happens every day, in every part of the country. Only a few days before the season began, Ronnie returned to Ohio. But our partner’s longed for smile was unseen behind the marble chill of death. There were no words to say. There was nothing to be done. Just a glacier of pain, and the funeral, and going on.

Read Next: The Hunt for the Jameson Buck, a 250-Inch Legend That Lived in an Old Strip Mine

Hot chocolate at dawn and staghorn sumac on the Clear Fork Hills bring Ronnie to mind. I usually smile, a little embarrassed, to remember that we thought we were doing him the favor, that first season years ago. Many days of haunting the hardwood ridges have made it very clear. Ronnie’s youthful cheer and enthusiasm and the days we shared were far greater gifts than we can ever repay and can only hope we deserved.

Read the full article here