This story, The Last Big Bass: Old Fighter,” appeared in the October 1973 issue of Outdoor Life.

The river was quiet. An owl had been calling earlier in the evening, but now it was close to midnight, and he had stopped. Occasionally a big bullfrog downstream broke the stillness with a series of bellows, then again there was only the constant rushing of water over a nearby shoal.

Wrapped in quilts, I lay beneath a makeshift lean-to made of a big brown tarpaulin that kept off the dew but not the chill of the early-summer night.

Next to me, Grandpa was snoring softly. Hollowed-out beds on gravelbars would never be as comfortable for me as they were for him. His 63 years of life on the river had accustomed him to that sort of thing. It was June 1961, and I was 13 years old — about to enter my first year of high school. I wasn’t much interested in English literature or math or history, but I was intent upon learning the important things in life, like how to build a johnboat, run a rough shoal, or set trotlines to catch big catfish.

I had good teachers. My dad and granddad spent most of their spare time on the Piney with me. We hunted the river in the fall and we always went fishing in the summer. Dad preferred to tempt smallmouths and goggle-eyes (rock bass) with artificial lures, but Grandpa was a trotline fisherman. We went after big flathead catfish at every opportunity. I lay there watching the sky light up occasionally from a distant thunderstorm and thinking about the other trips we had taken that summer. Finally I got up to gather some wood.

The campfire that had been burning so well only an hour before now lay in orange embers, with faint blue flames that licked up occasionally around the charred logs. Sparks leaped high as I rekindled the fire. There was no reason to go back to sleep now.

I sat down beside the fire and moved the coffee pot a little closer. The flames began to grow again, gradually illuminating a small area of the gravelbar.

I poured a cup of coffee as Grandpa continued to snore. Soon that built-in alarm clock of his would awaken him, and we would run the trotlines. I could picture a 20-pound flathead lashing with every ounce of his strength against one of our lines.

It was a good night for trotlining. Occasionally, distant lightning would silhouette the southern Missouri hills against the sky, and rumbles of thunder, muffled by distance, would follow.

Grandpa had said it would storm some before dawn, and he was usually right. To him, a storm pretty nearly guaranteed that he’d get a big catfish.

As the coffee chased away the chill, Grandpa stirred, then got up and joined me at the fire.

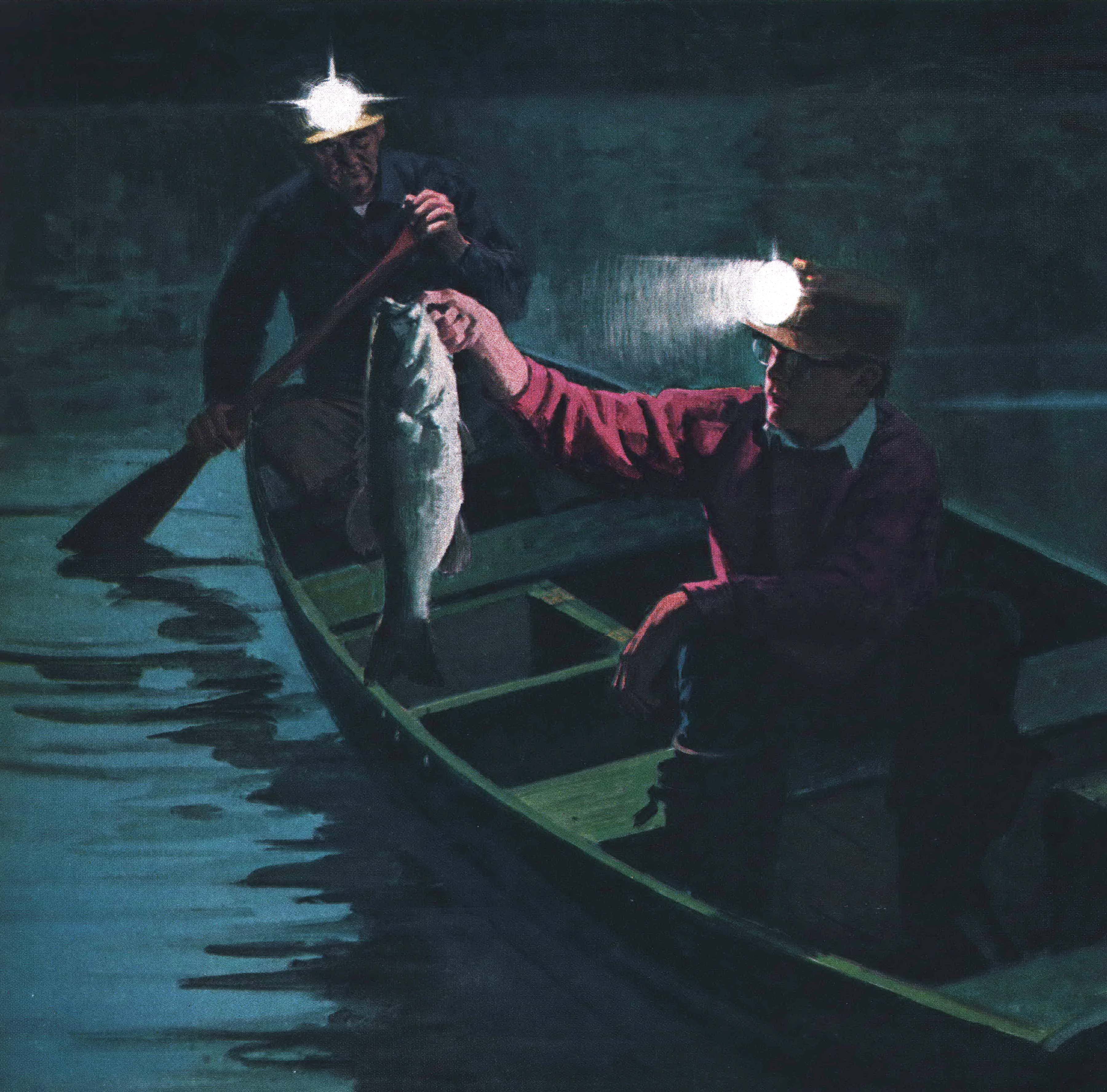

He filled and lighted the carbide lamps as he downed a cup of coffee. Such lamps were tools of the trade for the old-time trotline fisherman. The lamps are a simple means of providing light, and they leave the hands free. They are the same type as those that miners once wore mounted on their caps by a special frame. A lower cup is filled with carbide, and an upper compartment is filled with water. As the water drips slowly to the lower cup, an acetylene gas is formed. The gas is channeled to a tiny spout. The light from the flame that is fed by the gas is directed by a four-to-six-inch reflector, softly lighting a large area. The lamps were a part of trotlining as Grandpa knew it, and he refused to change.

The river looks somber in the light of a carbide lamp, like you might imagine it looked at the dawn of man, when mammoths walked the earth. The mist that rose from the water, the silence, and the chill set an eerie mood. We switched our bait from the boat’s built-in live-box to a bucket and then pushed off in the johnboat to check and rebait the lines.

I watched our campfire disappear around the bend behind us as I listened to the slurp of Grandpa’s paddle blade entering and leaving the water. Grandpa pushed our boat forward into the deep water of the Ginseng eddy. The Ginseng is a big, deep eddy on the upper Big Piney at the point where the river is closest to Houston, Missouri, only five or six miles away. It was one of a dozen or so eddies on the river that Grandpa favored.

As we prepared to run our lines, a whippoorwill began to call.

Trotlines are not easy to set, and it takes a lot of experience to learn how • and where to set them. The best places to set trotlines are in the deepest eddies — quiet water with big rocks, ledges, or bluffs beneath which big flatheads of 20 to 30 pounds find a place to hide.

The main line is tied from one bank to the other and is stretched fairly tight. Big catfish hooks are attached to the main line with nylon stagings or dropper lines about 15 inches long. Hooks must be three feet apart, and knots in the main line keep the dropper lines and hooks from sliding and becoming entangled. Rock weights of about fist-size are tied on after every fourth hook to carry the line to the bottom where the flatheads lurk. It’s a rugged sport — and a dangerous one. Heavy lines must be handled with care. Many anglers have become entangled in weighted trotlines and drowned.

Grandpa found the first line along the bank and lifted it with his paddle blade for me to take. As we moved along the line toward the deeper water, I felt the trotline surging in my hand, and I imagined a catfish just ahead.

It would have been easier for me to have lived a generation ago, not knowing that someday there would he an end to such streams. But perhaps future generations — never having known the quality of a living, natural environment — will not miss the Ozark streams.

Finally the fish surfaced only a short distance away, and I glimpsed a big brown body in the glow of the carbide lamp. Grandpa maneuvered the boat and gave advice as I excitedly hauled in the big fish.

Grandpa whistled softly as I laid the big fish in the bottom of the boat. It wasn’t a catfish; it was a giant smallmouth bass, somewhere between six and seven pounds.

Everyone around knew of this particular fish — Old Fighter, the smallmouth that had earned a reputation as King of the Ginseng eddy. But until now he’d never been boated. I looked at him for a while. He was by far the biggest smallmouth I’d ever seen.

My father was one of the many fishermen who had hooked and lost this big bass. Dad and I floated the river often, trying to catch big smallmouths on lures. I had seen Dad catch big bronzebacks on artificial lures, andfishing the Big Piney by myself — I had caught several two-to-three-pounders on minnows and nightcrawlers. But never had I dreamed of catching a fish like Old Fighter.

Bass aren’t usually caught on a trotline, especially with bait as large as Grandpa liked to use. Grandpa baited his lines with big chubs and suckers six to 10 inches long, and with doughgut minnows, otherwise known as stone-rollers. These aren’t as attractive to bass as they are to catfish, but we had used a few longear sunfish, and the enormous smallmouth had taken a liking to one of them.

Old Fighter’s dark brown body, broad and deep, glistened in the lamplight as he lay in the bottom of the boat. Even in defeat, the bright red eye that faced up blazed defiantly. “Old Fighter himself,” Grandpa said. “Thought I’d never see the day he’d leave this river. Maybe we oughta turn him loose, seein’ as how we was after catfish anyway.”

Immediately I protested. “It’s not against the law; so why shouldn’t I keep him?”

“No reason a’tall,” Grandpa answered as he began to rebait the trotline. “He’s yours, an’ a fine trophy.”

Reassured, I laid the bronzeback in the live-box. The fish was nearly too big for the well; when he felt water again, he furiously sought freedom. But finally he lay there on his side in resignation, his tail bent upward out of the water.

As Grandpa hooked minnows to the hooks along the trotline, I watched the fish, slowly moving his gills from time to time but otherwise motionless.

“I’ll see if Dad will have him mounted,” I said. “Then I’ll have him forever.”

The old man across the boat from me reached for another minnow as the faint rumble of thunder drowned out the whippoorwill’s call.

“They was a time,” he said, “when I thought big smallmouth would live forever in these Ozark rivers. That was years ago, before they began to cut the trees along the Big Piney and water cattle on the shoals. An’ it was before they hauled gravel out for cement, an’ let the silt an’ mud yellow the water an’ fill the eddies.”

He paused to bend a straightened hook, then peered into the minnow bucket, looking for a big doughgut.

“There was lots of Old Fighters when I was a boy.” In the light of the headlamp Grandpa hooked another big minnow through the lips. “We oughta have a big flathead on this’n come mornin’. Specially if that thunderhead moves on over this way.”

“Grandpa,” I said, still thinking about the big smallmouth, “do you think there’s any more like him in the Piney?”

“I don’t reckon,” he replied. “Fact is, they prob’ly ain’t many left half his size. But I guess they’d not get much bigger anyway if folks get the dam in they been wantin’.

“I hear tell the dam would mean lots more money for everybody,” he continued. “I can’t figger why the brown bass an’ the mink an’ kingfishers and such things ain’t worth nothin’ to nobody.”

Grandpa baited the last hook, then lifted the line to see that it wasn’t hung up on anything. Finally he dropped the trotline, and we watched it sink from sight into the depths of the Ginseng. Then he picked up the paddle and headed slowly back upstream toward camp.

“You know, boy,” he said quietly, “I guess me an’ that old bass got a lot in common. He’s probly layin’ in the live-box thinkin’ over his life, bein’ thankful he lived when the rivers ran clear and free, ‘fore folks knowed about dams an’ lakes and such. I ‘spect he’s obliged he lived when he did, ’cause he knows the world is achangin’ an’ there ain’t gonna be a place for him much longer. An’ when I look back an’ remember all the happy days an’ nights I’ve spent along these ol’ river bluffs, I kinda understand how he feels. Maybe a little sad, but mostly mighty thankful for gettin’ to be what he was.”

We moved closer to camp against the current, and I noticed that with the coming of the storm things were getting quiet. Lightning suddenly silhouetted the riverbanks again, and close behind the flash thunder rolled-louder now. I knew we’d be moving our beds and equipment to the big cave along the bluff behind the gravelbar for the rest of the night. Despite the approaching storm, I felt secure just knowing the cave was there.

Then I reached inside the live-well and grasped the big bass by the lower jaw, lifting him high so I could see him close up.

“We’re after catfish,” I said finally, lowering the bass into the water beside the boat. “Not bass.”

Together Grandpa and I watched the big bass. He lay motionless in the quiet water for a moment, as though uncertain of his freedom. Suddenly, with a powerful sweep of his tail, he shot away in the direction of the Ginseng eddy, where he would continue for a while to rule the dark, quiet water beneath the great white bluff.

To taste the quality, to hear the sounds, see the sights, and smell the aroma of a living, free-flowing stream makes a man feel close to the perfection of God’s creation.

The Ginseng eddy has been more fortunate than others. It still looks much the way it did then, though big hunks of algae float along the surface during the summer. Other eddies that I once trotlined can be waded now. There are stumps where century-old sycamores shaded the Big Piney of the past, and just below the Ginseng eddy a landowner recently bulldozed the trees from a long stretch along the stream. The rumored dam didn’t materialize, though the possibility of one is still mentioned.

Read Next: The Master Catfish Trotliners of the White River

Each year the Big Piney continues to be cleared; often miles of riverbank are bulldozed, exposed to the erosion of spring floods.

In my memory lingers that streak of brown moving away in the dim light of my carbide lamp. They are gone now — my grandfather and the big smallmouth. The Big Piney that they knew is gone too. In its place is a polluted stream, the product of an Ozark so bound for quantity in jobs and economy that the quality of the land has been sacrificed.

Other Ozark Streams

A handful of Ozark streams remain natural and free. Most of these streams — eight of them including the Piney — are in Arkansas, where the Corps of Engineers continues with its program of damming.

The Buffalo has been saved by federal legislation, though real-estate developers are organizing opposition, hut the other navigable streams appear to be either threatened or doomed. In Arkansas’ Ouachita mountains the Cossatot is now being dammed. It is the last remaining of seven free-flowing navigable streams in the Ouachitas. Now they are all gone, buried beneath reservoirs, living only in the memories of those who once knew the quality of a free-flowing Ouachita stream.

Now the Corps has made plans to dam one of the wildest, most valuable free-flowing streams in the Arkansas Ozarks: the Strawberry River. It is a stream of beauty, with bluffs, springs, and wildlife in abundance. Along its course are caves that were once used as homes by the Ozark bluff-dweller Indians.

They are gone now — my grandfather and the big smallmouth. The Big Piney that they knew is gone too. In its place is a polluted stream, the product of an Ozark so bound for quantity in jobs and economy that the quality of the land has been sacrificed.

A two-month study that was done for the Corps by Arkansas State University at Jonesboro in 1972 will determine that the Strawberry is not really of any value in its natural state. Instead, according to a preliminary draft of the study, a lake is needed for more waterskiing and more resorts, cottages, real-estate developments, and retirement homes.

A Corps representative told me last year that such environmental impact statements as the one being prepared for the Strawberry are a waste of the taxpayers’ money. He claimed that the project would be completed with or without such a study — and I don’t know of any impact statement the Corps has ever made that suggested such a project should not be undertaken.

Projects like the one planned for the Strawberry are pushed by powerful real-estate interests and out-of-state investors. As the Strawberry River study was being made, a large real-estate and land-developing company was buying surrounding land.

There is not another free-flowing stream like the Strawberry River in the eastern Arkansas Ozarks, yet within 40 miles of the Strawberry are two major reservoirs — Bull Shoals and Norfork — and within 60 miles lies Greer’s Ferry Reservoir.

Such massive, developed reservoirs seem to be the destiny of Ozark streams. Other floatable Arkansas streams th.at have been subjects of controversy or named as candidates for flood-control dams include the Mulberry, Eleven Point, and Crooked Creek. The remaining two, Kings and War Eagle, seem safe for the present (they flow directly into Table Rock and Beaver reservoirs).

I have stood on a bluff overlooking the Strawberry. I know that somewhere in those depths another last Old Fighter watches an unsuspecting minnow. It would have been easier for me to have lived a generation ago, not knowing that someday there would be an end to such streams. But perhaps future generations — never having known the quality of a living, natural environment — will not miss the Ozark streams.

To we who live during the present transition, however, watching the Corps (which is too powerful to be questioned, too strong to be stopped) methodically destroy the streams for the sake of another.

Read the full article here