This story, “Better Pheasant Hunting Alone,” was originally published in the October 1984 issue of Outdoor Life.

Over the past several years, I’ve kept records on more than 100 pheasant hunts. During that time, I’ve hunted both alone and with as many as nine other gunners. All in all, I’ve come up with some pretty interesting figures. For instance, my take on solo hunts has averaged more than twice that of when I was with two or more other people.

The reason for the increased bag, in my opinion, is that it’s a lot better to try to outsmart pheasants than to outnumber them. This is especially true late in the season when the birds you’re hunting have earned their educations by avoiding hunters.

Roosters aren’t exactly Einsteins, but they usually don’t stick around if they know they’re being hunted. Two people probably make three times as much noise as does the solo hunter. Three or four hunters can sometimes sound like an army marching through a field. Not only do extra hunters add extra pairs of feet, but there’s always the temptation to start talking or joking back and forth. When hunting alone, I like to take advantage of the quietness to beat pheasants at their own game-being sneaky.

I especially remember one morning when my young Golden Retriever, Mysti, and I were out battling kneedeep snow drifts and zero-degree cold in hopes of outsmarting a few cock birds. After drawing a blank at one spot, I headed for some favored late-season cover.

This 200-yard strip of thick cedars and underbrush bordering a milo field was a haven for pheasants. Unfortunately, it was also popular with pheasant hunters. While driving past the area, I noticed numerous tire marks and footprints. It had obviously been hunted at least twice since the last fresh snow a week earlier. Unlike my predecessors, though, I didn’t park in an old homestead near the trees.

Instead, I continued until I dropped down in a small dip in the road that put me out of sight of the cover. Quietly leaving the car, I put the dog at heel and slipped into a deep waterway that angled to within 30 yards of the far end of the cedars. My plan was to not only use the waterway to enter the trees unseen, but to surprise the birds even more by coming in from a different direction than they were accustomed to.

Slinking through the last 100 yards of the waterway in a crouch, Mysti and I quietly entered the cover. I’d no sooner given the dog the hand signal to hunt when she pushed up a pair of hens. A few seconds later, another bird flushed behind a cedar, never revealing itself for identification.

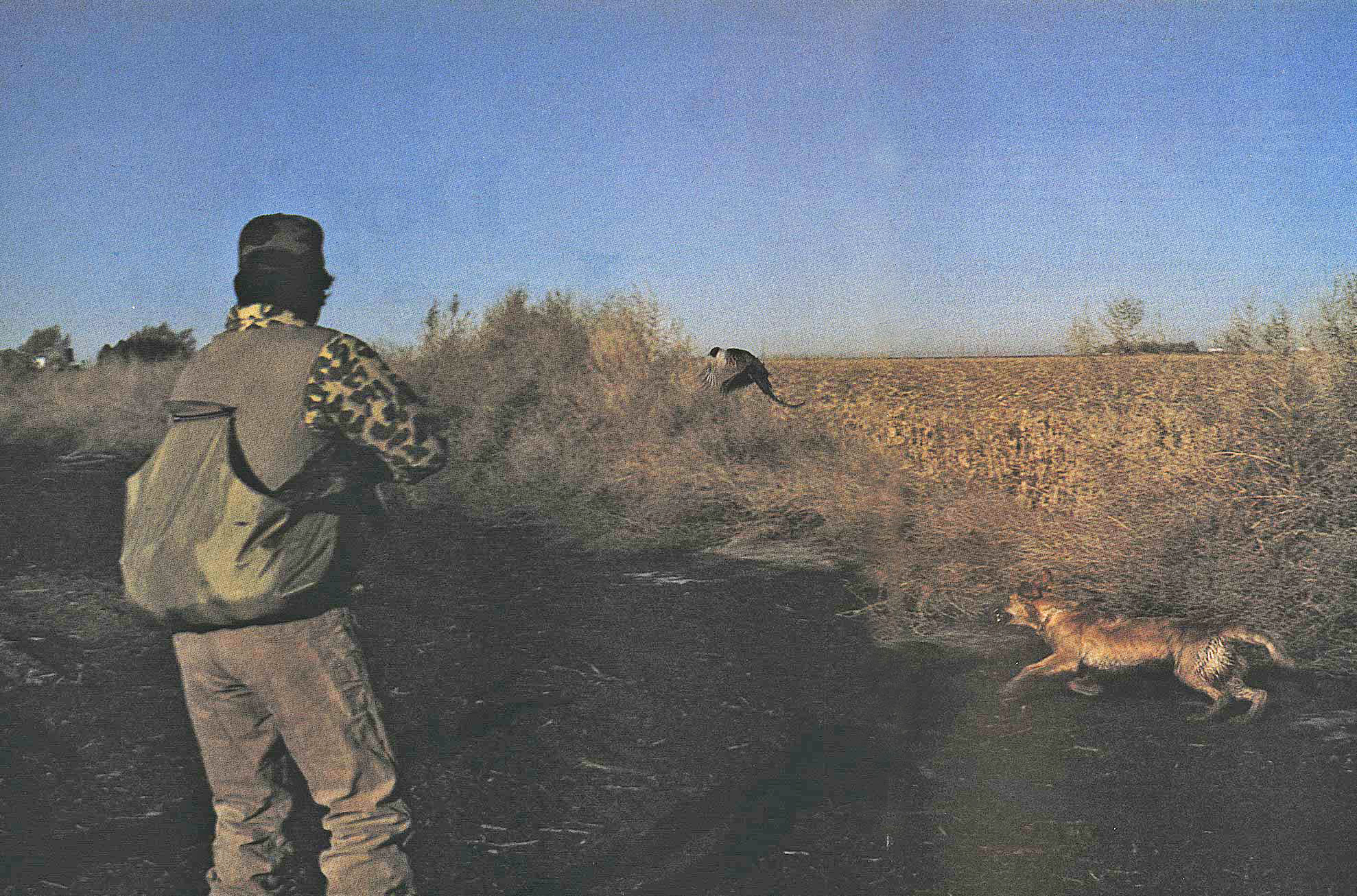

Moving quietly in the soft snow, Mysti began working a trail. Doing my best to keep up with her, I was forced to duck through thick stands of cedars that often sent an avalanche of cedar twigs and snow down the back of my neck. Halfway down the cover, I could see my dog’s pace quicken as the scent got stronger to her right. Anticipating the flush, I headed for the edge. I’d no sooner made it than a cackling rooster came streaking by. At the shot, the bird folded and plowed full speed into a snowdrift.

Admiring the retrieved pheasant, I was proud to see that it carried three-quarter-inch spurs-the equivalent of a big 10-point whitetail to a dedicated pheasant hunter. Thinking back, I realized that three of the five longest-spurred birds I’d ever taken had come on solo hunts.

When you’re out hunting alone, remember that the kind of cover you select can make a big difference between success and failure. Trying to hunt a big, wide patch of weeds or grass can make the hunting difficult even if there are a lot of birds in it. Roosters have a nasty habit of running circles around you if they’ve got enough room.

Instead, I like to stick to smaller, thicker areas that I can easily work thoroughly. Some of my favorite areas are deep and narrow draws, waterways, thick creek bottoms, overgrown ditches, patches of cattails, and the like. Remember to try to come in unseen. Hunt as quietly as possible and work the cover thoroughly.

There’s no doubt that a good dog is a big advantage to a pheasant hunter. But remember that a bad dog is even more of a handicap than no dog at all. It’s important that the dog works close and stays under control. A dog that ranges wildly or has to be shouted at to be kept under control might as well be forced to heel and be used only on downed birds.

The dogless hunter, however, can still kill his share of roosters with a little extra work. Without any four-legged help, it’s up to the gunner to squirm and pull his way through thick tangles. Zigzagging back and forth often helps, as does the old trick of pausing every so often in hopes of unnerving any tight-sitting birds.

No matter how quiet you try to be, sooner or later you ‘re going to find yourself behind a bunch of feathered track stars that would rather run than fly. Watching the dog, following tracks in the snow, or actually seeing the birds up ahead of you are sure tip-offs.

At times, you can drive the birds to places where they’ll hold better. Working an area toward an open piece of ground or a field of green wheat will sometimes get the birds to hold long enough for you to get within gun range. On the other hand, if you push a rooster toward a section of knee-high grassland or stubble, you’re just about out of luck as the bird will probably keep right on running.

You may do well to drive running birds into thicker cover where they may feel more secure in sitting. This tactic has worked for me many times in one of my favored lateseason hotspots. At the end of a good waterway lies a patch of some of the densest cattails and plum thickets imaginable. More than once I’ve tracked birds the entire length of the waterway without getting one to flush. At other times, I’ve had as many as 50 get up out of a stretch of cattails that probably covers less ground than an average house.

Another solo hunting tactic that I use if I think there are a bunch of runners in the group of pheasants is to fake the birds into thinking that there’s someone at the other end of the cover waiting for them. Where possible, I’ll drive to where I expect to exit a draw or creek bottom, get out of my car, and maybe shut a car door or even hunt a ways before quietly slipping around to come in from the other end. It’s a lot of extra work but it has paid off in the past.

Sometimes I’ll hunt halfway through cover using a break in a hill, ditch, or creek, slip unseen into the other end, then start hunting back in the direction from which I came. Thinking he’s boxed in, an old cock bird will sometimes just decide to sit tight. I’ve followed tracks in the snow where this has happened.

One of my favorite ways of taking late-season roosters is to make what I call “rooster raids.” I’ll spend most of the day hunting very small, often isolated clumps of cover that are at times no bigger than my living room. The whole key to the commando like maneuver is total surprise.

After drinking a cup of coffee and eating a roll in celebration of taking that longspurred rooster in the cedars, I decided to do a little raiding. Less than one-quarter mile from a friend’s house is a wide creek bottom that bisects a grainfield. Early in the season, you can find birds scattered about anywhere along the bottom. But when there’s snow on the ground, they usually head for a particular plum thicket. Located on a small bluff on the north side of the creek, it’s perfect for the birds. Most of the thicket is down out of the cold north wind and they can sun themselves for much of the day while being up high enough to see several hundred yards in almost every direction. The key word here is almost.

Swinging way around and keeping the dog at heel, I came in from the west using some small cedars and a slight rise in the hill to keep out of sight. Easing up to within 10 yards of the upper edge of the thicket, I decided to get dramatic. Yelling, “Charge,” I sent Mysti in while I went up to watch the action. Caught totally off guard, the dozen or so birds in the thicket panicked. Hens ran frantically to the edges and flushed. The lone rooster in the mob kept trying to rise straight up out of the jungle, cackling every time he hit a branch. On his third try, he finally made it airborne but was cut off by a load of Premium No. 7½.

A little common sense can help you determine good places for raids. The plum thicket described above is a good example. Keep in mind that the birds usually aren’t too far away from feed. Not only does that mean grainfields but also weed patches and big feed bales that are normally stored by farmers. Should you happen to stumble onto a bunch of birds in a particular cover, keep the place in mind. If the birds spooked wildly and you didn’t get a shot, plan a strategy that will work out better next time. Pheasants are often forced to be creatures of habit late in the season when life gets hard for them. Where you find them one day, you just might find them the next.

Late one Saturday afternoon last season, five of us stumbled onto a creek bottom that was literally full of pheasants. As it was, things got a little unorganized and we only managed to bag one rooster each. Believe me, there were enough birds for us to have taken at least twice as many.

A steady drizzle was falling when Mysti and I sneaked back down into that same creek bottom a few days later. We had just a half-hour of daylight remaining and, thus far, it had been one of those days. I had missed my only shot of the day and was coming down with the flu. I was a little discouraged, to say the least.

Slipping along quietly, we’d only gone a short distance when Mysti pounced into some thick tangles. Two roosters flushed, heading to my left. I fired quickly and both roosters went down. Suddenly, ·things were looking better. Continuing on down the bottom, I picked up another two birds for my limit, and made it back to the car with five minutes of legal shooting time to spare.

The lone gunner is often out of luck when it comes to hunting big grainfields where the birds are feeding. Those who have a dog, though, can often get some shooting by forgetting about following a set pattern and simply sticking with the dog and hoping for the best. One morning last season, I was able to bag a pair of roosters from an 80-acre wheat stubble field by letting my dog hunt at will.

Read Next: The Best Upland Hunting Vests of 2025

To some hunters, the most frustrating thing in the world is to see pheasants sitting on the snow, feeding out in the open. Trying to walk up on birds you can see will almost always result in failure. Instead, I like to try to gently spook the pheasants into some nearby cover that’s thick enough to either be hunted or raided.

After trying a few more unsuccessful raids following the plum thicket affair, I took a short lunch break and headed for a draw that had yielded a few roosters in the past. While pulling into the barnyard to ask for permission to hunt, I nearly wrecked my car as I looked out over the wheatfield that butted up against the draw. I counted an even 50 pheasants feeding within plain sight of the house, and 13 of them were longtailed roosters that glimmered in the afternoon sun.

The farmer gave me the OK to hunt, provided I hunt away from the house. Leaving my gun and the dog.in the car, I stepped into the open where the birds could see me. Then, I just stood there. After a few minutes of nervous pacing back and forth, the entire flock either strolled or flew down into a clump of cedars in the draw.

After giving the birds time to settle in, I began a stalk using an old shelterbelt and a fenceline for cover. Popping over the edge of the draw, I could see pheasant heads sticking up everywhere. The first bird up was a rooster that gave me an easy shot-I connected. I spent the next few seconds trying to distinguish roosters from hens as the birds filtered through the tops of the cedars. After a miss, I managed to down a bird. It took a little dog work, but it wasn’t long before Mysti caught up with the fourth and final rooster of the day. My solo tactics had worked again.

Read the full article here