This story, “Spark Plug Marlin,” appeared in the February 1983 issue of Outdoor Life.

For many years I was the owner and operator of several hunting preserves in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Now that I’m retired, my wife Rita and I spend our winters in Rincon de Guayabito, a small resort village in Nayarit, Mexico.

We come to this resort area every year to sportfish — mainly for yellowfin tuna, dolphin and sailfish. I bring my 15½-foot Star-craft boat and 35-horsepower Johnson outboard motor all the way from where I live the rest of the year in Tioga, Pennsylvania.

When I’m not out fishing, I stay in my 31-foot trailer that I also bring from home. I’ve seen some pretty big marlin taken from the waters out from our little village, but I had never fished specifically for them.

One day I asked the commercial fishermen in the area to bring back all the chub mackerel they caught so I could use it for bait on a trip to the marlin grounds. They brought back five of the foot-long mackerel, so I cut the whole bellies out, slit one end for a tail and put a hook in the front part.

The next morning I headed out to where I had seen marlin before and trolled for five hours without one strike. I headed back to camp. “Oh, well,” I said to myself. “There’s always tomorrow.” When I got back to camp late that afternoon, two more mackerel were lying on the ground by my truck, so I cut the belly strips for the next day.

That evening Rita and l were playing cards with Stan Sutton and his wife, Sally. The Suttons are from Glens Falls, New York, where they own Sutton’s Farm Market. The conversation got around to fishing, and soon to marlin.

“Need a fishing partner?” Stan asked when I said that I was going out for marlin again the next day.

“I’d be glad to take you along,” I replied, “because if I did hook on to one it would take a long time to boat it, perhaps all night.” Stan wasn’t deterred, so I had a fishing buddy.

Next morning at 5:30 I heard Stan tapping on my trailer. By 6:15 we were already out past the small island off Rincon, on our way to the marlin grounds 15 miles offshore. Soon our bait was skipping about 50 to 60 feet behind the Starcraft while we bounced along at about 4 or 5 mph.

A few hours later, a spark plug started missing in my outboard. (Gas in Mexico is of a lower octane than gas in the United States and often causes carbon problems.) The motor soon quit, so I got out some tools and began replacing the plug. The boat bobbed up and down with the ground swells of the ocean and the baits drifted downward with the same slow, swinging motion.

I put the new plug in and pulled the starter rope, but before we could get under way one of the reels made a couple of clicks. I slammed the gear forward and the gas to full throttle, and the No. 9 Penn reel began screaming. More than 100 yards of 100- pound monofilament flew off the reel.

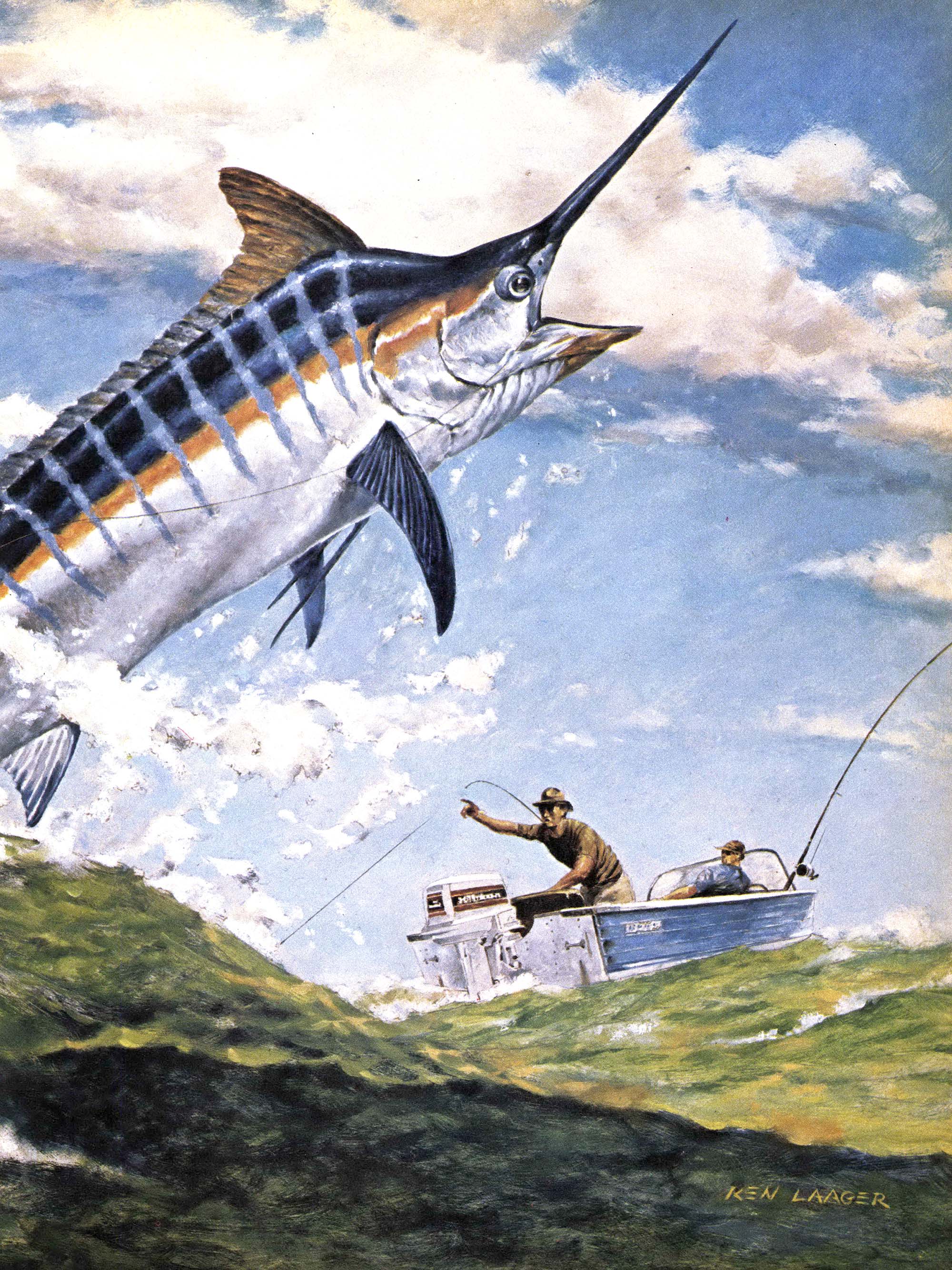

Our eyes were riveted on the foaming wake behind the boat. Suddenly a huge fish torpedoed out of the water, its steely blue sides glistening in the sun.

“My God, we got a blue marlin!” Stan yelled.

“That’s what we came out here for and we sure got a big one!” I shouted. I had stopped the boat by then because our hands were full of bucking rod, screaming reel and a leaping monstrosity attached to the other end of the line that looked to be nearly as long as my boat. Suddenly the fish made another 100-yard run.

Excitedly anticipating the marlin’s second jump, we were startled to see a huge dolphin leaping out of the water instead. Right on the dolphin’s tail was our marlin, trying to throw the hook with its acrobatics. It entered the water again and started submarining right at us. I reeled in as fast as I could but saw that there was still slack in the line. The line soon tightened up though, and the smiles on our faces were a yard wide, for we knew we had a good hook in the fish.

For the next three hours we just hung on to the rod and let the marlin tow the boat around at 4 mph. During this time we slowly recovered all of our line except for 200 feet. The marlin didn’t break water for those three hours, choosing instead to run and dive and bulldog beneath the surface. I looked at Stan gripping the rod as we were being pulled farther out to sea. He had recently won a camp-sponsored fishing derby bringing in two sailfish.

“How long can it keep this up, Stan?” I asked.

Stan raised his head and, looking a little tired from his half-hour turn of holding the rod, replied, “It’s slowing down quite a bit. How long have we had it?” I checked my watch. It was going on four hours.

As I took over the rod for my 30-minute stint, the marlin began sounding. 0l’ Blue was getting to the bottom as fast as it could and the amount of line on the reel was getting smaller and smaller. I set the drag tighter and tighter. The rod holder I was wearing started moving up past my belt. I couldn’t maintain the pressure any longer and so I held the rod right on the gunwale of the boat-and the marlin still went deeper.

I looked at the reel a little apprehensively and said to Stan, “There’s less than 150 yards left. We’d better get that other rod and reel fastened to this outfit and we’ll let it go over when all the line runs out.”

Stan hurriedly fastened the extra line to our reel. By now I was down to 80 feet of line, but the marlin was slowing down because I had the drag really screwed tight. When about 50 feet of line was left, the marlin stopped sounding, but we were still prepared to let rod and reel go over the side. But the line didn’t move! It stayed as tight as a string on a banjo.

The next turn I took with the rod was the most exhausting half-hour of my life. The tremendous strain on the rod forced us to shorten our turns to 20 minutes each. When Stan finally took over he just sat there with the pole bent in a full arc and with absolutely no action on the end. When it was my turn again, Stan tried prying the rod tip up in hopes of getting some line, but the rod would just spring right back down.

Stan wearily sat down with a thoughtful look on his face. Finally he said, “Something’s the matter. We haven’t felt the fish on the line for nearly two hours.”

I tried to remember everything I had learned about marlin fishing. Marlin that sound after a lengthy battle, I knew, sometimes died. Could our marlin be dead 900 feet below? The only way to find out would be to start the motor and see if we could move the fish.

With the guides on the rod at a 90° angle, Stan held the midsection of the rod while I grasped the butt end and put the motor in gear. For several minutes we didn’t move at all, knowing that at any moment the line might break. Just as we were beginning to think the situation was hopeless, we began to crawl ahead inch by inch. The line eventually angled in the water. Cautiously I pushed the throttle ahead a little more, but 15 minutes later we had hardly moved.

Stan suggested that we try it in reverse, but the water was too rough and we took some water in over the transom. After trying forward again for about 10 minutes, we realized that we would never get any line back at that snail’s pace. The only other alternative was to turn the boat and again head back toward the angle of the line.

Coming out of the turn, I gave the motor more throttle. Suddenly we picked up 30 feet of line. We continued this system of taking in line and within an hour we had the reel nearly full.

We’ve got it made, I thought. But then Stan hollered, “The reel won’t turn!” It had frozen up.

“We can’t lose this fish after getting this close,” I said. Grasping the line with my bare hands, I strained against the weight until I thought my fingers would be cut off from the line buried in my palms. But ever so slowly I piled up yard after yard of line in the boat. Soon we looked down in the water and saw a white shape coming closer. It was the belly of our marlin rising to the surface! We had outdone it, and it was ours —after seven hours and 15 minutes.

By now the sun was beginning to set and we were 30 long miles away from our camp. In celebration, we decided to split our only beer before returning to camp. It wasn’t champagne, but it tasted just as good.

We turned our attention to towing a 500 to 600-pound fish to shore through rough seas. Stan suggested that we tow it by the tail but when we did, the fish swung back and forth in a five-foot arc behind the boat, impeding our progress. I suggested that we put some half-hitches through its gill and around its bill, but Stan thought we should boat it to make better time. I didn’t see how we could ever get the fish in the boat, but we gave it a try.

With both of us standing close to the edge of the boat and pulling, the port side became dangerously level with the water. So we moved back and heaved again, and slowly the fish’s head and part of its body came on board — but no more. We couldn’t budge it an inch farther. Grabbing the rope that was still tied to its tail, I heaved again and the huge fish slipped right in on me. I was standing with my foot braced in front of the back seat when the tremendous hulk came to rest against my knee, wedging it painfully against the back seat. There was no way to move the fish, so I tried to move my leg. I turned my leg with a wrenching twist and with some more struggling, I was finally able to wiggle free. My leg hurt but seemed in one piece, and I was thankful that I didn’t have a serious injury.

We started the motor and slowly moved ahead, the boat riding dangerously low in the water. All that weight in a 15 1/2 foot boat, though, combined with improper balance, caused water to spray in the stern. With the great fish’s bulk filling the boat, there was no way to bail. How much water could we take on? With dusk creeping in, we knew we were in a tight spot with no one out in that lonely ocean to help us.

The only alternative was to head toward shore very slowly. The first wave broke in the boat and my eyes met Stan’s for a brief moment. We looked away quickly, each with our own thoughts. It was dark by now and the ocean was beginning to get even rougher.

For an hour we continued this hair-raising procedure, but then suddenly the wind died and the ocean smoothed out. I cautiously inched the throttle ahead. We had two packs of matches, and every once in a while we would strike one to read the compass heading. With the weight we were carrying it was difficult to keep a straight course.

Finally we saw a most welcome sight — lights on the horizon. With luck, we would be at our park within an hour or so. We passed the small island off Rincon and entered the bay, and our spirits rose higher.

Eventually we distinguished the outline of the beach and thanked God we had made it. In the dim light I could make out figures on shore, and I yelled that we were back. Soon the camp horn was blowing. Eager hands helped us to the beach and our craft was soon nestled on dry sand.

After looking at the size of that marlin again, we knew that a fish that big didn’t belong in our little skiff. By now people were coming from every direction. Flashbulbs were firing as, with the help of five men, we dragged the huge fish out of the boat. We wrestled it over to the weighing rack and hoisted it up, the poles creaking and waving.

From tip of bill to fork of tail, our marlin was 11 feet 5 inches. It weighed 504 pounds. After much picture-taking we removed the entrails, salted the interior and left the fish to hang overnight.

With the help of many hands and sharp knives the next morning, we set about the task of reducing the fish to pan size. That evening we had a fish fry for 67 people. Our marlin was good eating and we had a memorable feast.

Next year we will be heading back to Rincon de Guayabito with our Starcraft boat for another fishing experience. If we have any luck at all, the spark plug will foul up again at just that spot in the ocean where a prize fish is waiting for the bait to drift down.

Read the full article here