It was more of an “I thought I saw it” than a real movement that drew my attention to some thick weeds and grass on the lip of a small terrace about 85 yards below. Through my 7X35 binoculars, I scrutinized the spot for several minutes before finally picking out the dark, fuzzy tine of an antler, then a second. At first, I thought there were two bucks bedded together; the portions of antler that I could make out were too far apart to belong to the same animal.

But that impression didn’t last long. An involuntary tremble ran through me all the way to my bootlaces when the antler pieces moved in unison. The longer I looked, the more obvious it became that one buck belonged to both antlers!

The gentle September breeze wandered uphill, softly rattling the aspen leaves overhead as I carefully studied§ the steep terrain leading to the bedded mule deer. The hillside was littered with old discarded aspen branches of various sizes and other assorted “crunchies.” It didn’t take any effort to imagine the noise a misguided footstep would make in that stuff. The disturbing lack of ”man-size” cover presented another problem — getting within good bow range was going to be a painfully slow process.

Scarcely 15 yards to the front and slightly downhill, the unsuspecting buck lazily flicked an ear and surveyed the slope below its bed.

A meager string of quakey saplings ran from the inside part of the terrace, angling toward the edge. If I could just get to that screen of small trees undetected, I might have a chance. Slipping the binoculars inside my shirt and drawing in a half dozen long, deep breaths, I began to descend the slope, inches at a time.

Read Next: Best Compound Bows of 2024, Tested, and Reviewed

An hour, maybe more, passed before I eased up next to a weathered old aspen rooted on the lip of the terrace. Scarcely 15 yards to the front and slightly downhill, the unsuspecting buck lazily flicked an ear and surveyed the slope below its bed.

My foot began an uncontrollable little dance as I coaxed it silently forward a few more inches. I had to force myself not to look at the buck’s awesome head gear, but to concentrate as hard as l could on a small crease in the hair, just in front of the deer’s hindquarter and below the spine. As the sight pin hovered on the aiming point, I was a bit startled to see the feathers of an arrow magically appear, then vanish in that exact spot. I had completed the shot without really knowing it.

During that moment of the 1979 Colorado bow season, I didn’t know-nor did I care-that I was about to put my tag on the best typical mule deer ever taken by a: bowhunter. l only knew that I had just shot my first buck deer with a bow. My only concern was to make sure that I recovered the animal. And the thought of records had nothing to do with it. I suppose that this attitude was more a result of my upbringing than anything else.

Thirty years ago, I had the good fortune to be born into a Louisville, Colorado, family with a genuine love of the outdoors. Although my parents weren’t big-game hunters. by the time l was old enough to go on my first deer hunt, I had been taught a pretty valuable lesson; the real motivation and satisfaction in hunting or fishing comes from doing it right within the law. Filling a license or a bag limit is a bonus to be enjoyed at the dinner table.

My first couple of big-game hunts with a rifle weren’t anything spectacular, but they were exciting and challenging experiences. By the time my second gun season had ended, I knew that I was hooked on deer hunting. l wanted to hunt as often as the law would allow and to explore as much new country as possible.

Perhaps it was the extra chance to hunt, or just the mystique and romance of bowhunting that lured me into the sport. I’m not really sure. For whatever reason, I made my first bowhunt when the ’72 Colorado bowhunting season opened. Looking back on it now, I know that’s when my hunting education really started. It took five sometimes-frustrating but always-educational seasons before I managed to arrow my first deer. It was not one of the many big bucks I’d been introduced to over the years, but a doe muley. Nevertheless, taking that deer was a most important ingredient in my confidence as a bowhunter.

By the time the ‘79 Colorado bowhunting season rolled around, I had bowhuntcd seven consecutive years with just that one deer to show for it; that’s if you don’t count the many “lessons” the velvety-crowned teachers had subjected me to over that period.

I had also found out a hunting area that was generously sprinkled with more big bucks than most bowhunters had seen or would ever see. Over the past three seasons, I had hunted the area extensively without so much as a glimpse of another human. This lack of other hunters, no doubt, accounted for the incredible number of bucks. It was not uncommon to see from 30 to 50 antlered animals a day. with many of them falling into the category of real wall-hangers. These circumstances provoked in me a mysterious case of amnesia whenever anyone asked about my hunting plans. It also meant that I would be making another solo deer safari in 1979.

One evening ay dinner, a few days before the season opener, I was grousing a little about another solitary expedition.

“Why don’t you ask one of the guys from the archery shop to go with you?” my father, Warren suggested.

“I thought about it, Dad, but good hunting spots only stay that way by being unknown. Besides, everybody has already made their plans for this season.”

“Since you don’t want to give away your secret spot and you don’t want to camp alone, how about dad and me going along?” asked my mother, Edie. “We can drive the camper over and do some fishing and hiking while you’re chasing those fuzzy-horned deer. I might even cook for you,” she offered.

“Well, how about it son?”, Dad said. “Your mom and I can get away for the first couple of weeks in September, and we haven’t been camping together for a long time.”

My widening grin served as an answer, and it was settled. The season opened during the last week of August, but I could wait to start my serious hunting.

The season was six days old as I loaded my vehicle for a two-week stay in that prized hunting spot. My parents would join me in a few days, after checking out the fishing in some of the nearby lakes. Although I hadn’t been to the area since the previous year, it was easy to envision the steep, rugged slopes reaching above 9,000 feet and the giant aspens with just a hint of gold ringing their leaves. Heavy-beamed antlers. cloaked in velvet. were also part of my mind’s picture as I made the five-hour trip to that special piece of the White River National Forest in western Colorado.

Any one of them would make a great “first buck,” but two of the bucks carried awesome antlers — as big as anything I had ever seen.

Just before dark, I turned the rig onto a little-used four-wheel-drive trail. The road snaked its way through several miles of gambel oak, terminating at the base of an imposing ridge. Stretching up nearly 1,000 vertical feet in less than a mile, the ridge presented just the right amount of discouragement to keep most hunters from getting to the mountain that lay beyond. Vast tangles of oak brush dotted with small pockets of aspen choked off any easy routes up the slope. Several naked, rocky cliffs were the only interruptions in the leafy canopy. There was good deer hunting on the road side of the ridge, but the real Mother Lode lay protected in the stands of giant aspens that spread from the ridgetop up the flanks of the mountain.

On the way in, I passed two other hunting camps and wondered if anybody had tried the ridge. The untracked dust on the road indicated that the other hunters had probably stayed in the lower, more hospitable terrain. Reaching the end of the road, I quickly set up camp and readied my gear for the next morning. Since the area appeared undisturbed, I decided to hunt the front side of the ridge for the next couple of days. Besides, I had two weeks — plenty of time to make several climbs to the top if I had to.

A searing, month-old heatwave still gripped the area as daylight found me stillhunting the oak brush and small aspen patches on the lower reaches of the ridge. Cloudless days, coupled with temperatures in the high 90s, had reduced the hunting conditions to a noisy, uncomfortable sneak through the woods. And the bugs! Swarms of little black flies, Mosquitoes, and yellow jackets made stand hunting even more unbearable.

By noon of the fourth day, frustration escorted me back to camp. I was seeing plenty of deer, but most of them were does and fawns. I wanted to fill my tag with a buck. That wasn’t the pledge of a trophy hunter, just a desire to take my first buck with a bow — in fact, my first buck ever. My spirits brightened considerably when I saw the camper coming up the road. At least I wouldn’t have to suffer through anymore of my own-cooked meals on this trip.

That evening’s supper featured freshly caught trout, compliments of dad, and mom’s great sourdough biscuits. While we ate, we swapped accounts of the past four days. It was good to have people to talk to and the food couldn’t be beat. Refreshed by the great meal and the conversation, I shot a few practice arrows and got ready to turn in. I’d have to get an early start in the morning if I was going to tackle the ridge and hunt the big aspen patches on top. That had to be where the bucks were and I was bound and determined to find them.

Dawn was still more than an hour away as I started the grueling accent up the ridge. It would take at least that much hard hiking to reach a small clearing on the crest where I wanted to begin hunting. The darkness and tangled oak brush forced me to make several detours before I finally crept to the edge of the opening shortly after sunup.

Almost instantly, I saw the bobbing, velvet-covered racks of four bucks as they fed along the fringe of aspens on the other side of the clearing, about 80 yards away. Trying to get any closer through the knee-high brush that dotted the clearing would undoubtedly lead to being spotted by one of the deer, so I patiently watched as the bucks slowly faded into the aspen grove. Any one of them would make a great “first buck,” but two of the bucks carried awesome antlers — as big as anything I had ever seen.

The minutes dragged unmercifully as I waited to cross the clearing. I wanted to give the deer plenty of time to move far enough back into the aspens so they wouldn’t detect me. Twenty minutes later, I eased into the edge of the trees where the bucks had disappeared and began the tedious, gut-tightening process of trying to locate them: Move a few feet, pick apart the vegetation through the binoculars, and move a few feet more.

It took about an hour to thread my way 100 yards into the aspen grove. I was moving ever so slowly to the right, around a downed tree, when the morning stillness erupted in a brush-splintering, stick-cracking explosion of buck mule deer going in every direction. There wasn’t a chance for a shot and, even if there had been, I doubt if I could have pulled my bow. Several minutes passed before the jelly left my legs and I could move again.

The rest of the morning passed uneventfully. At about 11:30 a.m., I’d reached a small spring and had decided to eat lunch and take a short nap. A couple of hours later, I awoke to the droning of a yellow jacket squadron that was inspecting the remnants of my lunch. Gingerly picking up my gear, I moved off a few yards to plan my afternoon strategy.

I had been moving easterly most of the morning, so I decided to cut over a small saddle north of the spring and hunt my way back to the clearing. The long stand of big aspens blanketing the steep backside of the ridge had proven to be a hotspot for bucks in the past. A good game trail angled across the saddle and ran to the west along the high side of the ridge. Using the trail for quieter footing. I began my usual still hunting method.

Two hours had slipped by when I spotted an antler tip and part of an ear of a bedded buck. Carefully picking my steps, I managed to move within 45 yards before snapping a small twig that brought the big 5×5 to its feet; an arrow was on its way, but so was the buck and the two never quite got together.

After finding my arrow and confirming that I hadn’t connected, I began moving downhill in the general direction that the buck had taken. The deer wasn’t that badly spooked and I thought there might be a chance to hook up with the animal again. On a particularly steep pan of the hill, I came to another game trail that paralleled the ridgetop. Below the trail, a series of small terraces interrupted the slope ·s plunge to an oak-covered plateau some 1,200 feet below. Following the trail would allow me to glass many of the terraces from above, and I’d have the wind in my favor. The few deer tracks on the trail were definitely those of hefty animals, too.

Turning west along the trail, I renewed the slow process of visually probing every bush and shadow in the undergrowth of the aspen stand.

Occasionally, my progress was halted by the flitting of a bird or the rustling of some small animal in the vegetation. l had managed to cover more than 70 or 80 yards on the trail when my binoculars revealed the antler tips that I described at the beginning of this story.

As the feathers of my arrow were swallowed by the aiming point, the great buck shuddered and then just stretched out where he lay. I fumbled another arrow into place for a second shot. but it didn’t seem necessary. Snapping the shaft back in the bow quiver, I somehow forced my rubberlike legs to get me within 10 feet of the still deer.

Removing my camo head net, I noticed that the buck’s eyes were closed — definitely not the sign of a deceased deer! Before I could draw another arrow, the monstrous antlers jerked and the deer rocketed out of his bed, racing straight down the hill. Almost instantly, the buck fell and slid several yards on his back, only to regain his footing and disappear over the next little terrace below.

I know that it is normal to wait before following up an arrowed animal, but the thought of losing that deer immediately spurred me down to the place where the buck had gone out of sight. As I reached the lip of the terrace, I saw the giant — down for the count — 30yards lower on the slope.

I noticed that the buck’s eyes were closed — definitely not the sign of a deceased deer! Before I could draw another arrow, the monstrous antlers jerked and the deer rocketed out of his bed, racing straight down the hill.

From the first moment that I had seen the buck, I had successfully kept a magnum case of the shakes at bay. Now, they overtook me, and l had to sit down for a few minutes. Dozens of thoughts and feelings bombard a hunter at moments such as these, and I guess I experienced many of them. The realization that the “hunt” part of the season was over and the “work” part was about to begin slowly crept into my consciousness; and work it was going to be!

Approaching the fallen buck, I immediately knew that I had a major problem on my hands. The animal was an absolute monster. Any thoughts of getting the buck off that mountain single-handedly quickly vanished as I struggled with the field dressing chores. I mentally kicked myself for leaving the saw and the game hoist back in camp just so I could lighten my daypack for the climb up the ridge. I really could have used them both right now. Taking care of the deer as best l could, I gathered up my gear and headed for camp, three miles away. The heat and the insects hounded me all the way off the mountain, and I was concerned about the effect that they might have on the meat before morning.

Breaking away from the last oak-brush tangle, I met the aroma of freshly baked biscuits and the noises of someone setting the table for supper. I hollered a greeting and put my gear on the tailgate of the truck. As I got to the camper, Dad offered a tall glass of ice-cold tea through the doorway and then just stood there with a questioning look on his face. I took a couple of long pulls on the tea and then announced that I had killed “a buck.”

After the usual congratulatory handshakes and backslapping, we sat down to dinner and I went over all the details of the day. Even as we talked, the size of the antlers never really came up. I knew that the rack was way above average; one of the largest I had seen. But I also felt that I had encountered bigger bucks in this area before, including two of the foursome that I had seen that morning. I guess the satisfaction of taking my first buck kind of overshadowed everything else. Besides, there was still the little matter of getting the meat off the mountain. With supper over and the dishes done, I suggested to my parents that they might want to get a good night’s rest. Tomorrow, we had some work to do.

Getting the deer back to camp was all of the ordeal that I suspected it would be. The Barcus Team — mother, father, and son — labored until dark the next day, shuttling the quarters off the mountain. As incredible as it may sound, dad and I actually talked about leaving the cumbersome antlers behind. After all, the evidence of sex required by law could be met by much smaller, easier-to-haul parts of the buck, and we couldn’t eat the “horns” anyway.

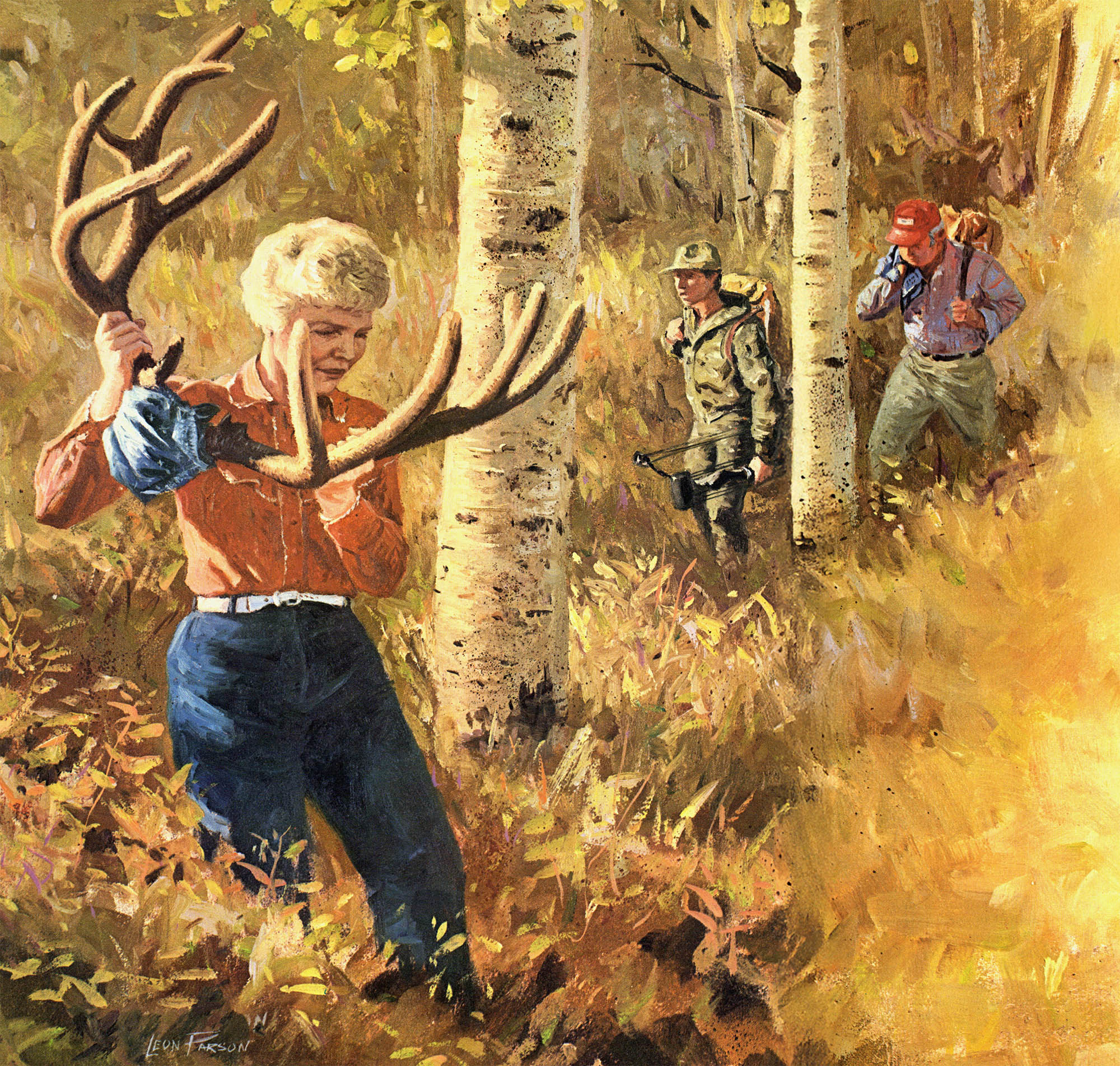

“That’s nonsense! I’ll carry them,” Mom insisted.

Taking the saw, she removed the antlers from the skull and patiently steered them through the brush, trees, and downfall all the way back to camp.

When I got home the next day, I took the antlers out to the garage and wired them to the rafter. That’s where they stayed until a friend of my sister’s stopped by for a short visit in February of 1984. A wildlife biologist for the U.S. Forest Service and a bowhunter himself, Bill Shuster immediately recognized the antlers as a potential record and suggested that I have them measured.

As incredible as it may sound, dad and I actually talked about leaving the cumbersome antlers behind.

Several weeks later, a measurer for the Pope and Young Club removed the velvet and officially scored my buck. Quite to my surprise. he informed me that the antlers were dimensionally equal to the largest typical mule deer known to exist — the Boone and Crockett record, belonging to Doug Burris, Jr. The main beams taped 28 6/8 inches, inside spread is 30 3/8 inches, and the greatest outside measurement is an astounding 38 inches! However, the length of four abnormal points substantially reduced the final score.

At 203 5/8 points, the buck exceeds the current record of 197 points, which belongs to another Colorado deer that was taken by Ronald E. Sniff in 1969. Official certification as the Pope and Young Club’s World Record for typical mule deer is likely to come at the Club’s biennial meeting in Bismarck, North Dakota, in late April.

Read Next: How to Insult Your Western Hunting Guide

A panel of Pope and Young Club judges will meet in the first week of March. My buck will then be measured and scored by two groups, consisting of three judges each. If the two groups’ scores for the rack do not agree, the judges must review their scoring process and resolve the discrepancy. This final score will be the official Pope and Young tally for my rack. If it breaks the current 197-point mark set in 1969, it will be announced as the new world-record typical mule deer at the Club’s meeting in April.

To think, if it hadn’t been for my mother, the 7×7 antlers might have dissolved due to exposure to the elements, instead of being here today. How do mothers always seem to know the right thing to do?

This story, “Bowhunting’s No.1 Mule Deer?” appeared in the March 1985 issue of Outdoor Life. The Barcus buck held the No. 1 spot in the P&Y record books for three decades, when it was replaced by a New Mexico buck in 2009. Today, the Barcus’ buck is the fifth largest typical mule deer taken with a bow on record.

Read the full article here