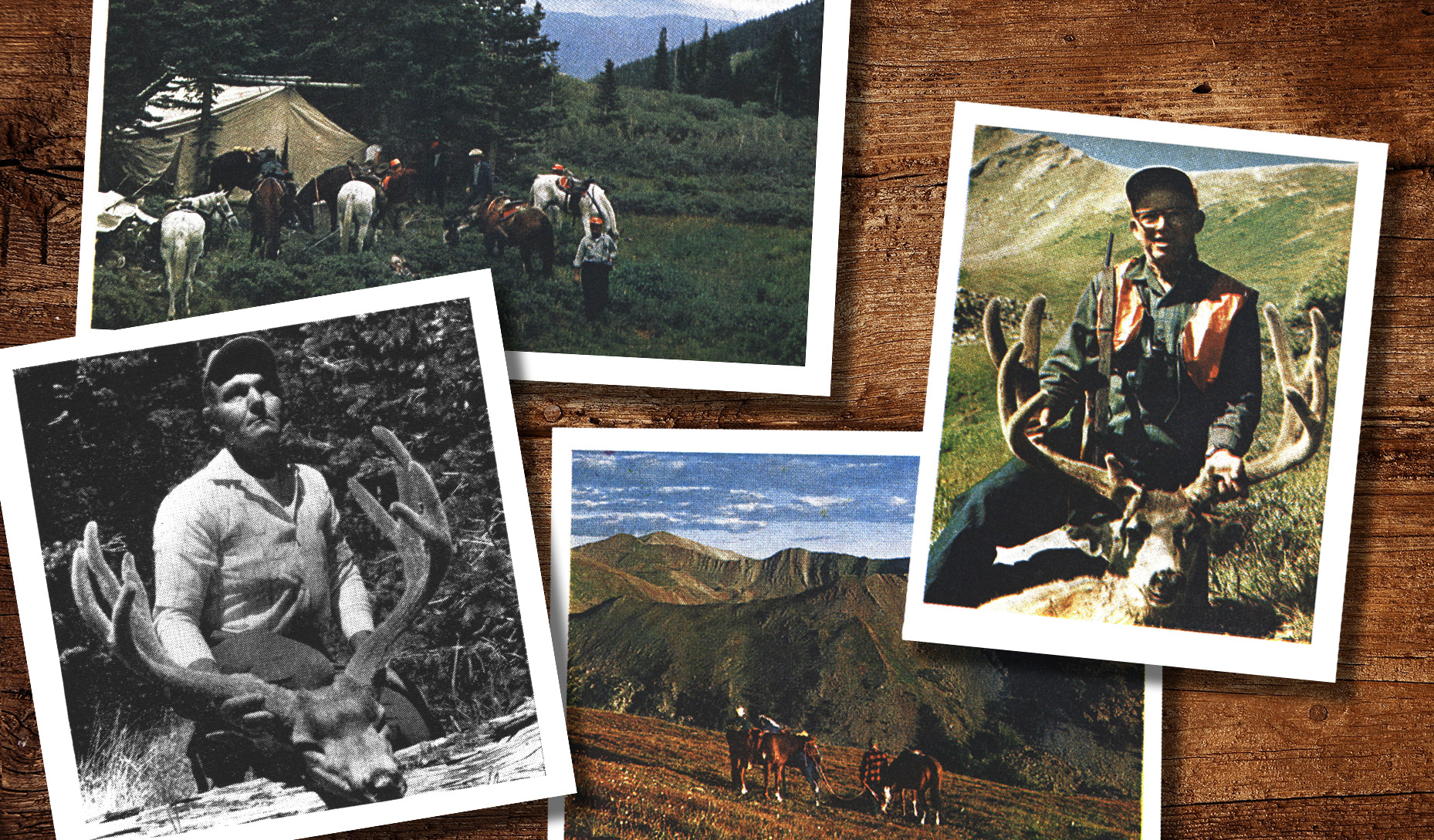

This story, “High in the Velvet,” appeared in the August 1970 issue of Outdoor Life.

I SELDOM PLAN a hunt without knowing just what I’m letting myself in for. With this trip, though, I almost bit off more than I could comfortably masticate. I backed into the safari almost before I knew it had happened. Jack Crock

ford was the culprit.

Jack is an old shooting partner of mine. Except for those too-few days a year when we are following the spoor of a deer, elk, mountain lion, or some such, he serves his fellow man as assistant director of the Georgia Game and Fish Commission. One blazing-hot July afternoon, Jack confided that his family orders called for a Labor Day visit with his son Bill, a cadet in the Air Force Academy near Colorado Springs.

“Where,” Jack asked me, “can I do some hunting out that way, at that time of year?”

“The July issue of OUTDOOR LIFE,” I said, “carried a story about the quality deer hunt that Colorado holds for a couple of weeks in late August and early September.”

“In that case, we could hunt either before the Air Force shindig, or afterward,” he told me.

“Where d’you get this ‘we’ stuff?” I asked.

“Well,” he admitted, “I’ve already made a few arrangements, and your name just happened to get into the plot. Our only problem is exactly when and where to go.”

“O.K., I’ll see if I can get some dope,” I finally said, thereby taking a hand in the game.

I picked up the phone and called Carl Welsh, a regional manager for the Colorado Division of Game, Fish and Parks. A few years before, I had been with Carl and his crew when we trapped a herd of antelope on the Colorado plains and trans ported them to Florida by air for stocking there (see “Antelope Play in Florida,” OUTDOOR LIFE, May 1966).

The facts Carl gave me ranged from interesting to disconcerting. The quality deer hunt was to be continued. This hunt originated in 1963 after wildlife census takers flying the high country had found out that many big bucks do not move to lower elevations but range in or near sheep terrain all winter. Dan Riggs, one of the game officers in the Sangre de Cristo area, then proposed a special early season so that some of the huge racks might be harvested be fore the high country became impassable except on snowshoes.

For the quality hunt, resident deer licenses at $10 and nonresident licenses at $50 are required, but permits to take deer in specific areas are free on a first-come, first-served basis. Only deer with four points or more on each side would be legal.

“There are some tremendous bucks around the top of the Sangre de Cristo,” Carl told me, “and I recommend that region, provided that your lungs, legs, and heart can take it. You’ll be hunting at twelve to fourteen-thousand feet.”

“Sounds like a cinch,” I lied. “How do we get up there?”

“We have a number of outstanding guides in the area,” Carl said. “KW Guides and Outfitters are good. They have a camping permit for Middle Brush Creek. That’s high, isolated territory. You get to it by packstring, and you’re not likely to have competition from other hunters there.”

Carl told me more about the KW. The outfit is owned and operated by Frank Kimmel and Terry Woodward, and 1969 was its second season of existence.

“However,” Carl added, “both boys are fine woodsmen and hunters. You should have no trouble filling out with quality racks.”

Hunting the high country by pack string was a fascinating prospect, but several things were causes for concern. One was altitude. I had done a bit of hunting between 10,000 and 11,000 feet, but I had never stalked game above 12,000 feet. Up there, the oxygen gets mighty thin, and the old pumper has a tough job. The heart is like any other muscle; without regular exercise, it gets out of shape. In that condition, over exertion can damage it or even put it out of commission entirely.

Then there was the length of the trip-seven days, but only five days of hunting. Jack and I would need some time to adjust to the altitude. Would that requirement still leave sufficient time to look over enough heads so that we would be sure of real trophies?

I have been in high country with fellows who fell by the wayside be cause they were not in good physical condition. At least, I could prepare myself in that respect, I decided. I started jogging. Every second morning at daylight, I drove to the football field of our local high school and trotted four times around the inside of the stadium. Four times around equals one mile. I made those first rounds very slowly, but gradually increased my pace until I could jog the four laps in a mite over nine minutes. If anyone had seen a bespeckled baldheaded old codger trotting around the football field between first light and sunup, he would surely have called the men in the white coats. I am also sure, however, that my mile every other day paid off on the hunt.

Over a two-week period before Jack and I arrived to hunt, Frank and Terry had made several scouting trips through the part of the Sangre de Cristo area open to the quality hunt. They had chosen Middle Brush Creek, where they’d found an abun dance of big-buck sign.

The campsite they selected was above 11,600 feet. It was far above the elevation where jeep trails run out and accessible only in the saddle or afoot.

It’s a place of barren ridges, tremendous rockslides, and rugged peaks — the home of the eagle, the cony, and the bighorn sheep. That wild, high country has a fascination of its own, for it is a land of sunshine and sudden storms, cerulean skies one moment and fog so thick you can cut it with a knife the next. We joined three other hunters for the ride to camp. One was Howard

W. Wolfe, a noted custom gunsmith from Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania. The two others were Donald L. Reider, a plant manager for Yorktown Kitchens; and Donald Ruhl Jr., a superintendent for the same firm.

Although Terry and Frank were in only their second season of outfitting for deer, elk, antelope, and packtrain fishing trips, they were operating smoothly and obviously knew their business on top of the world. The camp was well equipped, even to a tank of oxygen for high-altitude emergencies and a collimator, an instrument used to check the alignment of a barrel and scope with reasonable accuracy without firing a shot.

With guiding, wrangling, and other duties, the two partners were busy from their first predawn cups of coffee until we went to bed at night. Helping them were Clancy Lansford, a top guide; Bruce Wilson, a colorful former Marine; and Bob Kordula. Bruce Wilson assisted with the horses, wood, and water and did other camp chores. He was in training for his guide’s license. Bob Kordula was vacationing from his job as mechanical-arts instructor at North Junior High School in Colorado Springs. He was our cook. Before our first day in camp came to an end, I knew we were in the hands of an all-star cast.

Even though the rules said that only bucks with four or more points on a side were legal, I am certain that the five hunters in our party could have filled out opening day of the early season. There were many big deer on that mountain, but we wanted exceptional trophies.

At about the same moment, they both spotted a pair of legal four-pointers browsing on the side of a shallow draw. One buck carried a wide rack, and the other had a narrow, high set.

As it happened, Jack was the only man who made a fast kill. Shortly after daylight, he and I rode up a steep trail with Terry. It angled through the edge of the timber to a wide basin 1,000 feet higher than the camp. There the timber ran out into gnarled, runty spruce and scattered thickets of dwarf willow and mountain mahogany, a favorite deer browse.

We tied our horses in the taller trees at timberline. With the cold wind in our faces, we pussyfooted through the thinning scrub, pausing frequently to glass the terrain ahead. Both Jack and Terry have fine game eyes. At about the same moment, they both spotted a pair of legal four-pointers browsing on the side of a shallow draw. One buck carried a wide rack, and the other had a narrow, high set.

“How do they look?” Terry asked.

“That wide rack appeals to me,” Jack allowed.

“Go after him,” I suggested.

“Both are pretty good,” Terry said.

We stalked from one low spruce clump to another and got to within a few hundred yards before the bucks stopped browsing and looked directly at us.

“Better take him,” Terry said.

Jack glanced at me. “You go ahead,” I said.

Jack braced his .30/06 in place and we heard the 180-grain bullet hit. When the larger buck went down, the other deer pranced off a few feet and then came back. I studied him through my glasses.

“You want him?” Terry asked.

“If you don’t mind, I’d like to look for a better head.”

Terry grinned and said, “That’s all right with me.”

We dressed out the buck, and while Jack returned to camp for Bruce and a packhorse, Terry and I continued our hunt across the rough mountain side. After less than half a mile, we spotted a buck that looked about the same size as the one I had passed up earlier. We got within 50 yards of him, and I took a picture or two before the animal caught our scent and paced casually downhill into the protection of the timber a quarter-mile from us.

Since the weather was a bit on the warm side, Terry thought it wise to pack Jack’s meat out to the locker plant. So Howard Wolfe and I were assigned to Clancy Lansford.

I caught a rather forlorn look on Jack’s face.

“I sure got my season over in a hurry,” he said.

“Why don’t you come with us any way?” I asked.

He didn’t need much elbow wrenching to accept the invitation. The two Dons and Frank had planned to work a big basin at the head of the next water shed, so we started to hunt about where Jack had killed his buck the morning before.

The sun was peeping over the rim of a distant mountain range when Clancy spotted three bucks at least half a mile away. Through my 7X glasses, the largest rack seemed to be about as wide as the one Jack had taken, but it was a bit higher.

“We can get to him without much trouble,” Clancy said. “Who wants to make the try?”

“Howard hasn’t had a chance to shoot yet,” I said.

“That makes no difference,” Howard replied. “If you want him, he’s yours.”

The guide and I outvoted Howard against his wishes, so Jack and I remained where we were while Howard and Clancy made the stalk. They disappeared into the brush, and Jack kept his spotting scope on the bucks. When they stopped feeding and stared in our direction, we believed they had seen the hunters until a doe came past us not more than 30 feet away. She paused to look us over, and I held my rifle ready in case a trophy buck was following at her heels. She moved on, but no buck mule deer appeared.

A few minutes later we saw Howard’s buck go down. The shot was a long one. We later paced off the distance as best we could. With this information and the knowledge that the three-minute dot in Howard’s scope had covered the chest of the deer, we estimated the distance at about 600 yards. Howard’s custom built .300 Magnum had performed handsomely.

Melvin and Grandma, two packstring mules, had followed us up the trail from camp and were now on the hill side above Howard’s buck. We watched the mules work their way slowly around the upper rim of the basin. While Clancy was dressing out How ard’s deer, I suggested to Jack that we follow the contour on which we stood and stay below the mules in hopes they would flush a buck out of the scrub willows.

Walking slowly — you can’t do much more than that at those altitudes — Jack and I worked along among stunted trees, paralleling Melvin and Grandma. At one spot we had to cross a small opening to the next clump of trees. I was a step ahead of Jack when he hissed. At almost the same instant I spotted the round, velvet-covered tines of a rack sticking up above the brush. The deer was apparently lying down, and only the tops of his antlers were visible, but the rack looked good slightly better than the others that had been taken.

“You want him?” Jack asked in a whisper.

“I’d like to see the whole rack before I make up my mind,” I replied.

While we were trying to decide on a retreat to the trees behind us or a crawl to the next clump, Melvin and Grand ma took charge of the affair. They crashed through the brush directly above the deer, and the buck stood up. He was facing the mules and his rump was toward us.

“It’s a good rack,” Jack whispered.

“It’s a good rear end, too,” I replied, “and I can’t be sure of a quick kill if I shoot him there.”

The two mules blundered on toward the deer, and he suddenly whirled and fled at right angles to their approach. The rack looked enormous at that angle, and I got in a shot as he crossed an opening in the brush. I missed clean. The buck, with Melvin and Grandma at his heels, raced along with a small forkhorn that had appeared from somewhere. The deer went out of sight in the timber below us. Jack let out a laugh.

“If that wasn’t a three-ring circus,” he said, “I’ve never seen one.”

We returned to camp around noon and later hiked to Banjo Lake, up the creek a couple of miles and 1,000 feet higher in elevation, to sample some of the cutthroat fishing and watch for deer on the slopes above us.

That afternoon Don Ruhl brought in the widest, tallest trophy to date. Frank, his guide, reported seeing several high-racked bucks at the head of the next canyon.

“On the South Branch of the North Fork of Brush Creek,” he reported with precision.

Only a dim trail led across the rock slides and precipitous slopes into the hole, but Terry, Jack, and I decided to climb the tremendous ridge between our canyon and the South Branch so that we could look over into the big country beyond for outsize bucks.

We were out of camp by daylight. Each early-morning ride was an experience in itself. Late in August at those altitudes before the sun comes up, it is cold enough for a heavy coat. The peaks are bathed in heatless orange light, and you look down and see night in the canyons and valleys many thousands of feet below our mountain perch. We stopped occasionally to scan the patches of brush until we climbed the big ridge beyond them to a high point overlooking the tremendous canyon of the South Branch. There we ground hitched our horses and sat down to glass every cranny of the basin in which a buck could hide.

Jack was the first to locate two deer. They were feeding on an open hillside almost directly across from us. Then Terry spotted another pair of bucks browsing a hillside covered with willow and mahogany brush. Through our binoculars we could make out what seemed to be sizable trophies, so the guide set up his spotting scope for a close check.

“One buck carries an outstanding set of horns,” Terry said.

I studied him through the spotting scope. The head looked like Boone and Crockett caliber, but from long experience I knew that the farther away a buck stands, the bigger its rack seems.

“Let’s go down for a closer look,” I suggested.

“You’ll have more than one or two to examine,” Jack put in. “Look at what’s coming through that gap.”

Nine deer, all bucks, filed through the low saddle between the two prongs of North Brush Creek. Three of them carried racks that showed wide and tall in the glasses.

“I would guess that there’s no B. and C. in that bunch,” I said, “but at least they give us more of a choice.”

“You ready?” Terry asked.

“Why don’t you fellows leave me in my grandstand seat?” Jack asked. “I can’t help with the stalk, and I’d sure like to watch the show from here.”

When we rode off the ridgetop, 14 bucks were in sight. At its best, the trail we followed was dim, but Terry’s sharp eye worked out the way across angled slopes and rockslides to a small creek flanked by a low ridge. There we could remain out of sight and take an other look at the bucks. Several were lying down in the willows, among them two with the largest racks. We sprawled on our bellies on the slope, studying out the best approach.

From the crest of this ridge, we finally made a long detour down the creek.

“We’d best go afoot from here,” Terry advised us. “It’s a tough climb, but it might save us from spooking those deer with the horses.”

From Jack’s grandstand seat, the bottom of the basin looked flat. On the site, we found out that there were ridges, heaps of granite boulders, and sharp slopes. A dozen or more lusty creeks poured out of the basin.

Before we began the last phase of our stalk, Terry had selected the top of a high, steep hill that paralleled the brushy sidehill where we had last seen the deer. From that hill I would shoot. Jack continued to watch the show from his vantage point and told us later that he almost came down with buck fever when the deer got to their feet

Six of the bucks stood up in single file. They looked back as though they intended at any second to bound for the protection of the saddle on the skyline.

and began to group as though they in tended to take off through the saddle toward the next creek. Having no idea of the ruggedness of the country we were navigating, he wondered why we were so slow in our stalk.

Terry and I finally reached the top of the hill and crawled through the brush on our bellies to a sharp drop-off across from the spruce-and-willow patch. Whether a vagrant wisp of breeze carried our scent to the deer or they had seen us in spite of all our precautions I have no idea, but six of the bucks stood up in single file. They looked back as though they intended at any second to bound for the protection of the saddle on the skyline.

“Two big heads there,” Terry whispered. “You’ve got to choose between the one with the gray coat and the one in brown.”

There really wasn’t much time. The bucks were nervous. I did not have an opportunity to use my binoculars, so I tried to compare the bucks through my riflescope, which was set at 4X. Both racks seemed to be equally wide, but the one the brown buck was wearing looked higher.

“What range?” I asked in a whisper. “About three-hundred,” Terry answered. “Hold at the top of his back.”

I put the crosshairs on the buck’s spine and squeezed off a shot. The bullet must have hit slightly over and beyond him. The herd jumped nervously, and half the deer turned at an angle that would have taken them away along the sidehill if they had bolted.

“Try again,” Terry barked.

I held crosshairs lower. When I pulled the trigger of my custom .300 Kennon Magnum, the 180-grain Nosler bullet went home. The buck made two bounds and went down. He spilled end over-end down the steep slope until he disappeared in the brush.

“Stay right here, and keep your eye on the spot,” Terry told me. “That way we won’t lose him.”

After he found the buck in the thick brush, I joined him.

Howard measured the spread of the antlers at 31 inches. As it turned out, all four bucks we collected had similar antlers.

Don Reider was the only member of our party who did not take a deer. He could have shot a number of legal animals, but he had his heart set on a massive rack. The only huge one he saw appeared just at dusk far down one of the big slopes. The light was going fast. He and Frank did not have time for the kind of stalk that would have resulted in a sure kill.

“Well, sir, there’ll be another year,” was Don’s philosophical comment after it was all over.

Read Next: I Finally Drew a Bighorn Sheep Tag. I Was Too Out of Shape to Fill It

A caribou in the remote Yukon and that Colorado buck are the only two heads I have taken in velvet. Each time I look up at the well-scraped, well-mounted trophy on my den wall, I remember the beauty of that high, rugged Colorado country and one of the longest and most unusual stalks I have ever made.

Read the full article here