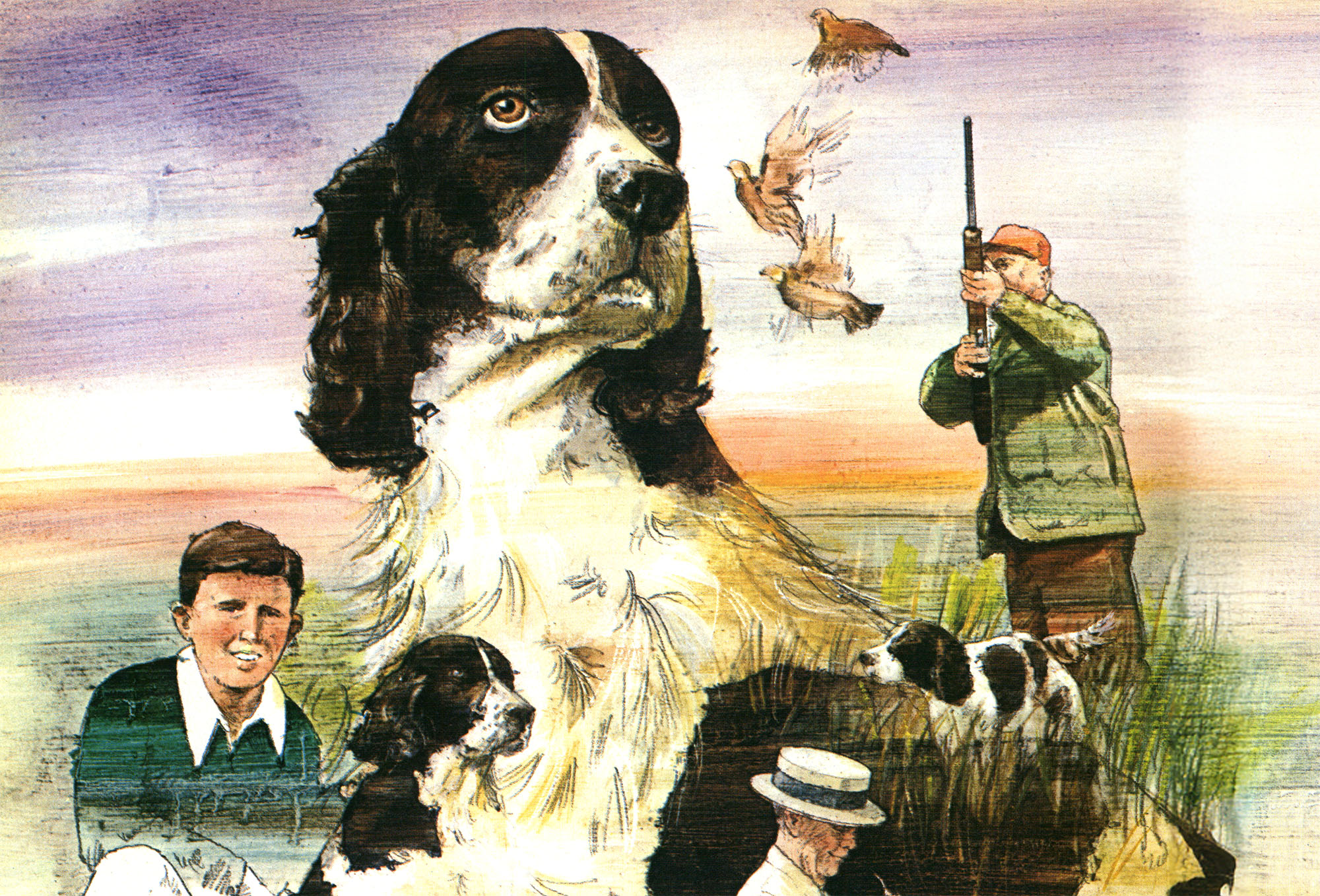

This story, “Jim the Wonder Dog,” appeared in the August 1985 issue of Outdoor Life. We are republishing it today, March 10, 1925, on what would be Jim’s 100th birthday. You can visit the Jim the Wonder Dog Museum in Marshall, Missouri.

Sam Van Arsdale wasn’t overly upset when his young Setter seemed untrainable. He had gotten it free as a pup. A traveling salesman named Taylor had stayed at Sam’s hotel in West Plains, Missouri, and they had talked of bird dogs. As a sort of joke, Taylor sent Sam a pup that he couldn’t sell for $5 out of a litter going for $25 apiece.

By late summer, trainer Ira Irvine was finding the March-born youngster impossible to coerce into doing anything. The dog walked from shade tree to shade tree and watched while three other youngsters learned to quarter and search for birds. Despite Irvine’s failure to even yard train the Setter, when Van Arsdale talked of giving the dog away, Irvine said, “If you do, let me have him. His eyes look almost humanly intelligent. I’d like to see what I can do with him.”

Irvine wasn’t the first to notice the dog’s intelligence. Back when Railway Express made the surprise delivery of the just weaned pup, Sam Yan Arsdale had to leave him with a young niece, Dorothy Martin. Sam was going on a month-long fishing trip. By the time Sam returned, the child was claiming that the pup “has sense. He understands what I say.”

Dorothy had played games with the pup. She’d hide, then call, and he’d find her. Finding her was simple for a dog with a decent nose, but staying put until called seemed highly unusual for a pup so small. He’d also lie patiently under a cardboard box while Dorothy hid her doll. When the child said “Find Dolly,” the little Setter would go straight to it without searching.

An experienced hunter, Sam attributed all this to superior nose and good retrieving instincts. Those excellent qualities were useless, though, if the dog couldn’t be trained to hunt. Finally, in November, quail season had opened, and Sam decided to waste no more time. He and Irvine would try the youngster in the field on birds. If the dog showed no interest, that would end the matter.

Irvine opened the gate to an old apple orchard and freed the 8-month-old Setter. Again, just as he had done as a pup with the doll, the young dog showed no signs of searching, but went straight to a covey of quail. He locked on point 20 feet from the birds. The quail flushed as Sam and Ira approached, but neither man shot. Incredibly, the youngster remained steady to flush like a finished dog.

The quail spread across the far end of the orchard as they lit. Again, without searching, the Setter went directly to a “single” and pointed. Either the youngster marked the birds amazingly well for an inexperienced dog, or he just “knew” where they were. Yan Arsdale shot the bird, and the untrained Setter stood steady to shot!

“Dead bird,” Sam said to the dog that had never heard those words before, and the Setter fetched the quail to Yan Arsdale’s hand.

The dog then pointed a pair. Sam downed both, and the dog retrieved them, on command, in the order shot. Ira shot a single, and the Setter delivered it to Sam. The untrainable dog, without training, suddenly had become completely trained.

Van Arsdale was excited over the prospect of hunting this dog. He didn’t seem particularly amazed, however, by the Setter’s rather uncanny hunting behavior. Indeed, over the next few years, during quail seasons, the man and dog did little else but hunt, sometimes in several states. Sam kept track of the birds they took until he lost count when the number topped 5,000. But Sam expected a dog to be just a dog. The Setter was 3 years old before the man realized that there was something about this canine that he couldn’t explain.

Long before that, of course, the dog had acquired a name. Sam saw a movie in which Will Rogers said, “I have no name, lady. You can just call me Jim.” Sam’s Setter had no name either, so Jim it was.

In rapid succession, Jim then identified a walnut, a stump, some hazel bushes, and finally a cedar that the dog had to run some distance to find.

Jim did not rise up an unknown out of nowhere, however. One of Jim’s grandfathers was Field Trial Hall-of-Farmer champion Candy Kid, a dog out of such greats as Caesar, Antonio, and Rodfield, very familiar names to any student of English Setters. Jim’s sire was another Hall-of-Famer: Eugene’s Ghost, out of the famous Eugene M. When yet another Hall-of-Farner, Nash Buckingham, was asked which was the greatest performer he ever saw at the Nationals, he replied without hesitation: “Eugene’s Ghost.” The genes of Bob Stoner’s Ghost dogs are still with us today through the dam of Wonsover’s Crockett Jed and on to his son, National Champion Johnny Crockett.

Jim was born March 10, 1925, but he was no field-trial dog. His deliberate manner of calmly going directly to the birds instead of racing from horizon to horizon would appeal to no judges. To a bird hunter like Sam, though, Jim was the perfect dog. Perhaps he was a little more. Yan Arsdale had begun to notice odd little things, such as Jim immediately going to the next field when Sam would express (he talked to the dog as he would another human) his belief that there were no birds in this one.

Finally, in October of Jim’s third year, Sam decided to stop for a rest. It was rather hot, so Sam said, “Jim, let’s go sit in the shade of that hickory tree over there.” The dog preceded him to the hickory.

Another coincidence? Yan Arsdale felt a little foolish but he decided to find out. “Jim, can you show me a black oak?”

Jim not only walked to a black oak, but put his paw on its trunk. In rapid succession, Jim then identified a walnut, a stump, some hazel bushes and, finally, a cedar that the dog had to run some distance to find.

Astounded, Sam raced home and told his wife, Pearl. She thought that it was nice to believe the dog was that smart, and it was all right to say such things to her “but please don’t tell this to anyone else.”

Sam forgot her warning by the next day when he met three friends on a downtown street. They listened, smiled, and dispersed without comment.

Sam continued to practice his “Jim, can you show me” requests, and the dog seemed infallible. By that time, the Van Arsdales had purchased another hotel that they were running in Sedalia, Missouri. One day, Sam was standing on the sidewalk talking to a man who had just parked his car nearby. “Jim,” Sam said, “can you show me this man’s car?” Jim walked down the street and put his paw on the correct car.

Word spread fast, and Sam freely allowed Jim to demonstrate his ability. “If that dog’s so smart,” someone shouted, “give him my license number, and let him find the car.” Jim did it. Locating a car by license number, either written or spoken, became a popular demonstration. Harvey Welch, now of Marshall, recalls seeing it done while he lived in Sedalia.

Most of the people who still remember Jim either did or do live in Marshall, Missouri, where Van Arsdale bought and ran the Ruff Hotel. Roy Reade, who was a barber across the street from the hotel, recalls his brother driving from Kansas for a visit. “When Mr. Yan Arsdale asked Jim to show us the man from Kansas,” Reade remembers, “Jim identified my brother by sort of striking him with a paw. I saw him do this sort of thing many times. What sticks in my mind most was his peculiar eyes. They were very different from an ordinary dog.”

Mrs. H. H. Harris, wife of a Marshall attorney, was at a hotel luncheon with a group of eight or 10 women when Jim was asked to identify the woman wearing a blue dress. He did it, despite the fact that dogs are thought to be color blind.

“I was playing bridge with the Van Arsdales and some neighbors,” said John Adams of Marshall, “when Sam asked Jim to find the man with the red tie. He put his paw on my leg.”

Realtor Leonard Van Dyke said that his father wrote insurance for the Ruff Hotel. Van Arsdale came in with Jim and asked, “Jim, what do I do when Mr. Van Dyke sends me a bill?” Jim placed his paw on the counter.

The elder Van Dyke and realtor Pete Rae’s father were with a group in the hotel when Sam asked Jim to identify the pair of Republicans. Jim touched both men. Leonard Yan Dyke thought that that particular incident could have been directed. And many people did believe that Sam Van Arsdale had a secret way of guiding Jim. Pete Rae, however, recalls seeing individuals write instructions on slips of paper that Sam didn’t bother to read. He simply told Jim to do whatever they asked.

Once, a hotel guest voiced disbelief, saying “That’s a bunch of baloney!” When Sam was ready to leave the group, he told Jim to first “show us who made a damn fool of himself in here tonight.” Jim placed his paw on the disbeliever.

People were laughed at when they repeated what they saw Jim do. Pete Rae brought his whole college class, plus the professor, to the hotel to prove his claims. When they left Jim, they were no longer laughing.

Marshall banker John Houston was a youngster at the time, but he recalls having lunch at the hotel with his folks while Jim was still alive. A high school teacher wrote out instructions in Latin, which Jim carried out despite the fact that Van Arsdale didn’t understand the language.

Over the years, Jim also followed instructions in German, French, Italian, Spanish, Greek, and shorthand. While performing for a class of Greek students, the professor wrote something in that language that Jim couldn’t seem to grasp. After two tries to get Jim moving, the embarrassed Yan Arsdale admitted that his dog was stumped and asked what the request had been. The professor had simply written the Greek alphabet.

“I also recall an incident,” said John Houston, “in which Jim provided answers that Mr. Van Arsdale didn’t know himself. My uncle Al Zimmer and his friend Jack Street were visiting from Kansas City. Mr. Van Arsdale didn’t know these men, but was prompted by my father to ask Jim who was in the grocery business and who has three children. Jim made the right choices.”

John Houston is rather typical of the people who remember Jim. Most of these people have deep roots in the area, are very intelligent, and are highly respected in the community. Many are professional people with good reason to protect their credibility. Yet they freely discuss Jim without fear of ridicule. Of the dozens of Marshall people interviewed, not one voiced disbelief in Jim’s abilities.

“Those of us who saw the dog know it happened — and that’s it,” said John Adams. “In fact, we were so used to the dog that we didn’t think about how amazing it was.”

Many people, usually newcomers, persisted in trying to catch Sam Van Arsdale directing his dog. When they couldn’t discern hand signals, or even eye movements, most decided that the dog was somehow reading Van Arsdale’s mind. But even that failed to explain everything. In order to follow written instructions that Van Arsdale didn’t understand, the dog had to be reading everybody else’s mind, as well. Small wonder that folks began calling him “Jim the Wonder Dog.”

“My mother was one of the skeptics,” said retired high school teacher Byrdie Lee McAlister. “The first time we encountered Jim was at my cousin’s house in Arrow Rock. Sam was there. He knew mother doubted so, when four women walked in, Sam asked, ‘Jim, which of these ladies is the dentist’s wife?’ That was mother, and the dog picked her out. She was pretty convinced after that.”

Byrdie’s mother and Pearl Van Arsdale’s mother were first cousins, so they visited regularly. On one occasion, Byrdie was with a group of five girls as they entered the hotel. All were wearing long coats that covered their dresses. “Sam asked Jim to pick out the girl wearing the blue dress,” Byrdie said. “I couldn’t see any blue showing out from under the coat, but Jim went directly to the right girl. I don’t know how Sam knew, either.”

(There is a simple explanation for Sam, of course. He noticed the legs as they walked through the door. A coat parted at the bottom, and blue flashed through. How Jim knew remains inexplicable because, as was mentioned before, dogs are supposed to be color blind.)

Jim was strictly Sam’s dog, according to Byrdie. Sometimes he’d do something for Pearl, sometimes not. Once, a group of reporters came from Kansas City when Sam was away, and Jim wouldn’t do a thing.

Pearl had a bunch of little pillows that she thought made the bed look nice, Byrdie recalls, but when Sam came upstairs to take a nap, he’d just throw them on the floor. Pearl fussed about that regularly. One day, Pearl went in after Sam had been napping and found Jim putting pillows back on the bed.

Most recollections of Jim are of feats beyond ordinary canine capability but, occasionally, there are glimpses suggesting that Jim did have limitations — that, in some ways at least, Jim was indeed a dog. During a hot day while the Van Arsdales still lived at their Sedalia hotel, Pearl noticed Jim panting heavily, and said, “Why don’t you go upstairs and let them give you a cool bath?” Jim left.

Long afterward, Pearl looked around, didn’t see Jim, and became concerned. Then she remembered her suggestion. She went upstairs and found Jim in the bathtub, still waiting for someone to draw the water. According to Byrdie, Pearl then said, “If you’re that smart, Jim, why didn’t you just turn on the water yourself?”

It seems out of character for Jim, but Betty Yan Arsdale, Sam’s niece by marriage, says that Pearl told her Jim rolled in dead fish like any other dog. Betty’s family visited Sam and Pearl often after the hotel owners retired, when they lived at Lake of the Ozarks.

Jim also picked up some human courtesies over the years. Van Arsdale’s niece, Dorothy Marshall, now living in St. Louis, recalls that Jim wouldn’t brush past you as another dog might. He’d walk around a human. He also seemed to exhibit human dignity. He wouldn’t romp or chase a ball. She doesn’t recall ever hearing Jim bark. He wouldn’t run up to, or play with, another dog. In fact, if another dog ran up to him, “he’d turn that dog off quick as a wink.”

Muzette Martin Pletcher is a sister of Dorothy Martin, the girl, now dead, who cared for Jim during the first month and who noticed that the dog “had sense.” Muzette recalls that Jim was “never doggy, never pestered.” Jim slept with the girls at first “because he yapped at night,” but he was not a barky dog later.

Muzette married Dr. K. E. Pletcher, now of Omaha, Nebraska. Dr. Pletcher hunted with Sam and Jim while he was in medical school. Jim was about 7. Earlier accounts claim that Jim would identify women (for whatever reason necessary, while performing) by placing his paw on them as he did men. By the time Dr. Pletcher knew him, Jim would no longer paw a woman. He’d sit in front of her.

Dorothy Marshall remembers that Jim always walked behind her, never in front. And, unlike an ordinary dog, he wouldn’t lie around where he could be stepped on. Once, a preacher started to go out of his way to step on Jim’s tail, and the dog scooted beyond reach almost as quickly as the man had the thought. “Few dogs have the sense to know when they’re in the way,” the preacher observed.

“Jim knew what you intended to do,” Yan Arsdale told the preacher.

Dorothy Marshall was in a hotel room with Pearl Van Arsdale when the latter was talking about Jim’s pups. “I have a picture of them around here somewhere,” Pearl said, and she rummaged all the way through a trunk to no avail. Finally, as she was about to abandon the search, Jim got up from where he had been lying the whole time, and placed his paw on a dresser drawer. Pearl pulled it open, and there was the picture.

Apparently, Van Arsdale bred Jim just the one time to an unknown bitch. He kept two of the males, Bud and Son, and the female, Jessie, went either to Colorado or to California. Whoopie, a third male, chewed through the back seat to get into the trunk of the car and also was given away. Dorothy Marshall has home movies of Sam working with Bud and Son. Dr. Pletcher remembers the two as “good bird dogs, but not the best I’ve seen.” Van Arsdale had hoped that one might inherit Jim’s unusual powers, but neither one did.

Jim didn’t resist obeying Van Arsdale’s requests, but the dog didn’t really enjoy performing. “You could depend on it,” said Dorothy Marshall. “If a car pulled up outside the hotel, and Jim went and hid in the baggage room, somebody would walk through the door asking, ‘Where’s Jim the Wonder Dog? I want to see him perform.’”

On at least one occasion, Jim did long distance mind reading. It started with an illness. In November of 1932, near the end of an especially long hunt, the dog hung his right front leg in a woven wire fence. Shortly afterward, Jim cooled himself in cold spring water. By the time they returned to the car, his leg buckled under him while he was trying to climb onto the seat. It became worse that night and veterinarian Dr. M.E. Gouges made a house call, pronouncing it rheumatism. By the next night, Jim wasn’t coming to Sam’s call and didn’t even seem to recognize him. At Dr. Gouges’ suggestion, Van Arsdale rushed Jim to Dr. J.C. Flynn in Kansas City. Dr. Pletcher recalls, “Sam thought that it was some kind of canine infantile paralysis. And it was a neural disorder. The right shoulder muscles were wasted, and Jim walked with a limp. After that, his right leg and paw were always out of line with the others.”

Anyhow, Jim stayed with Dr. Flynn for some time during the treatments. He even began performing for the veterinarian as he had for Sam. Dr. Flynn noticed that Jim would often start to obey before the request was put into words. Dr. Pletcher recalls noticing a similar behavior when Yan Arsdale would ask the dog to find a certain car; Jim would be on his way before Sam had said more than a couple of words.

“But most amazing,” said Dorothy Marshall, “was Jim’s response to the vet’s telephone. If an ordinary customer called, Jim didn’t move. But if Jim got up on the first ring and walked to the phone, Dr. Flynn knew that Sam would be on the line. Jim would sit by the veterinarian’s leg during the entire conversation.”

Word circulated that Jim was performing for Dr. Flynn. One day, when the veterinarian picked up a repaired tire at the garage, the owner asked to see the Wonder Dog perform. Dr. Flynn glanced around, saw the safe, and asked Jim where the man keeps his money. Jim walked to a pile of junk. The red-faced mechanic fished a can out of the pile and conceded that he’d have to find a new hiding place.

For performance on a grand scale, Jim’s finest hour was before a joint session of the Legislature at Jefferson City. Senators and representatives alike met in the House where Jim picked out people with various traits, including the gentleman “ladies speak of as tall and handsome” and which politician was playing cards instead of paying attention. Finally, Jim followed instructions sent in by Morse code, which Sam didn’t understand.

Jim performed many more feats of extrasensory perception. Some of them are in a book called Jim The Wonder Dog. Clarence Dewey Mitchell wrote it while Sam and Pearl still lived. Unfortunately, Mitchell wrote the book in the first person, if Jim were telling his autobiography, which adds a fairy-tale flavor to an already difficult-to-believe story. The incidents described in the book, however, were verified by Pearl Van Arsdale and others as occurrences that they had witnessed. Steve and David Hartwig, owners of Red Cross Pharmacy, 961 W. College, Marshall, MO 65340, had the book reprinted. It’s $6.95 postpaid.

There are also incidents in this article that are not in the book. And some known feats of ESP are not described in either, due to limits of space. But they all pale in the light of what Jim did next. It began with a kitten that J. Wilbur Cook picked up out of the snow and carried to the Ruff Hotel. By the following summer, “Flossie” was pregnant and about to give birth. Cook and Van Arsdale tore paper into several pieces and asked Jim to pull out as many as the cat would have kittens. Jim pawed out five.

Next they wrote “male” on five slips of paper and “female” on five more. “Jim,” said Sam, “show us how many of each there will be.” Jim selected three males and two females, which Flossie did indeed have one week later.

A dog predicting the future? Dorothy Marshall has no doubts that he could and did. “My brother’s wife, Eleanor, was having a baby,” Dorothy recalls. “My Aunt Jessie held a slip with ‘boy’ written on it, and Uncle Sam held ‘girl.’ Jim picked ‘boy.’ That baby was Bobby Marshall who is now a doctor in Denver.

“Jim also predicted races,” Dorothy went on. “Judge Seneca Taylor and his wife were great sports enthusiasts — he was head of the boxing commission, and she liked to play the horses. Uncle Sam wouldn’t bet on Jim’s predictions. He said that he didn’t understand the dog’s powers and wouldn’t take advantage of them. He usually wouldn’t let others do it, either. He was away fishing, though, so Mrs. Taylor convinced Pearl to see if Jim really could pick the winners. He pawed his choice from among the horses in the first race, and Mrs. Taylor bet $2. She won. They did this several times.

“Finally, Judge Taylor mentioned to Sam how well the girls were doing with Jim’s advice. That night, as they all played bridge, Sam chastised Jim in front of the group. ‘I’m surprised you’d do this,’ he said, knowing how I feel about it.’” A week later, Pearl and Mrs. Taylor figured that Jim had forgotten, so they tried again. Jim just looked at them, then walked away.”

Dorothy Marshall does remember one incident when Sam possibly did allow betting on Jim’s prediction. Perhaps it was the reason Sam tried so hard to prevent it thereafter. He was constantly worried that gambling interests would steal his amazing dog.

This incident began in Florida. Hunting and fishing were Sam’s life, Dorothy recalls, and he loved the wilds up north. Pearl liked linen tablecloths and being waited on, though, so he’d appease her with an occasional vacation in Florida. They were with the Henry Hunt family in Miami when someone asked if Jim could pick winners in the dog races.

It isn’t known if Sam was aware of it or not, but the Hunt youngsters began betting on Jim’s predictions. They couldn’t miss, and word got around. It even appeared in the newspaper. Sam received a telegram advising him to leave town if he wanted his dog alive. Sam and Pearl left that night.

Predictions by Jim included the 1936 World Series, when he picked the Yankees; the 1936 presidential election, when he picked Roosevelt over Landon; and the Kentucky Derby winners, which he picked correctly seven years in a row.

Sam not only refused to bet on Jim’s predictions, but he also turned down $364,000, which Paramount Studios offered if he and Jim would work in Hollywood for one year. A dog-food company would have paid well for an endorsement but Sam refused. Van Arsdale hunted Jim, walked Jim, and fed Jim as he would any other dog. Jim ate table scraps — although probably of a better grade then most canines received in those days. His favorite food was cornbread, Dorothy Marshall recalls.

Finally, on March 18, 1937, Sam and Jim were walking toward Lake of the Ozarks to go fishing when the dog faltered and fell. Sam grabbed Jim in his arms and rushed him to the vet in Sedalia. Jim breathed just twice on the table and died.

Dorothy Marshall still has a telegraph from Pearl that reads: JIM DIED 1 OCLOCK TODAY SAM’S GRIEF TERRIBLE. Later, Pearl told Dorothy that Sam came through the door of the Ruff Hotel, carrying Jim and crying like a baby. Sam Van Arsdale was a strong, very confident man with considerable dignity, but losing Jim devastated him.

Sam wanted to bury Jim in Marshall’s Park Ridge Cemetary, [sic] but the board of directors feared a precedent. Pat Hays, the sextant, said that he didn’t see what the fuss was about “since Jim was smarter than most people in here, anyhow.” But he was overruled. O.S. “Dub” Campbell embalmed Jim, and Sam had a special casket made because the available child’s casket would have required breaking the dog’s legs to make him fit. Sam also refused a request for Jim’s brains made by the University of Missouri.

Jim was buried just outside the cemetery’s fence. Ironically, the cemetery was expanded, the fence was removed, and Jim is now where Sam wanted him. In addition, Jim’s grave is at the edge of a plot of single graves for small children. The Van Arsdales never had a child.

In June of ’84, 47 years after Jim’s death, there was evidence of four different people having recently placed flowers at the headstone — two different plastic bouquets, fresh peonies in a cut-off milk jug, and even a live, long-stemmed red rose stuck into the ground. “People do this all the time,” said the Park Ridge caretaker. “Every day or two, somebody visits the grave or asks where it is. No other grave gets anywhere near this much attention.”

Who or what was Jim? One group questioned Dorothy Marshall at length and quickly became convinced that Jim was King Solomon reincarnated. They were, of course, reincarnationists. A few superstitious Missourians decided that Jim was the devil and had cast a spell on Sam for making him perform. They arrived at this conclusion because Sam had a stroke and was paralyzed for the last 10 years of his life.

Sam Van Arsdale certainly didn’t know who or what Jim was. When skeptics accused Sam of directing the dog, he’d respond with, “Show me how I do it. I’d like to know.”

“I asked Sam if he trained Jim,” said Dr. K.E. Pletcher. “He asked me, ‘Did you ever see another dog do anything like this? If I did train him, I’d be the greatest dog trainer of all time. I’d like to claim that, but I can’t.’”

Perhaps nobody cared to think of a dog as being that much smarter than themselves.

At one point, Van Arsdale took Jim to the University of Missouri in an effort to learn what gave the dog his powers. Jim was examined and declared physically no different from any other dog. “They gave him an intelligence test with slips of paper,” recalls Dorothy Marshall, “but came to no conclusion.” While John Houston was in a University of Missouri psychology class, he remembers the professor saying that the dog had been there, but that nothing could be determined.

The obvious question is, of course, didn’t anyone ask the dog who or what he was? Jim had repeatedly demonstrated an ability to answer yes or no, true or false, or multiple choice questions by indicating with his paw. A researcher could have gotten right into the dog’s mind, almost conversationally, with spoken questions and possible answers on pieces of paper. But nobody did. Nearly every person interviewed was asked this question, and each registered surprise. They hadn’t thought of it. Apparently, their image of a dog got in the way. Despite what Jim showed them he was capable of, they just wanted him to perform. Perhaps nobody cared to think of a dog as being that much smarter than themselves.

A possibility remains for those who would speculate. People who are severely mentally handicapped — and who also are deaf and dumb — have sat down at a piano and played flawless classical music. Other mentally handicapped people, without education and with no other knowledge or apparent ability, have been able to solve complex mathematical problems in their heads with the speed of a computer. Through some yet unexplained quirk, perhaps chemical or physical, their otherwise imperfect brains are, in one area, superior to “normal.”

Read Next: A Young Pup, an Old Setter, and a Point I’ll Never Forget

“I’ve never seen that in an animal,” said Dr. Pletcher, “but I went to grammar school with a boy named Bus Ferrel who never had a piano lesson. Yet, if you whistled a tune, he could immediately play it, all the flourishes included. He had a gift similar to those mentally handicapped folks who have a single, extremely developed automatic ability, but Bus was not mentally handicapped.”

That’s all well and good, but what about Jim? Was he devil, or angel, or King Solomon, as a few would have us believe? Or was he just a reminder of how little we know about the brain — or what’s possible for a brain, even a dog’s, if we can discover how to use more than the 1 percent we now employ?

Read the full article here