This story, “They Find Lost Men,” appeared in the June 1964 issue of Outdoor Life.

Nobody foresaw, at the time it happened, that when Harold Patrick froze to death on a moose hunt in the bush north of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, in December 1958, his death would spark a search-and-rescue organization that would be the means of saving an unknown number of lives. But that’s how it turned out.

Patrick went into the Pancake River country, 50 miles north of the Canadian Soo, driving a jeep back on a woods trail with two companions, then leaving them to hunt by himself. He did not come out.

His partners returned to Sault Ste. Marie and reported him lost, and the usual search started at Highway, runs along its southern and western sides; another goes north from Thessalon to Chapleau, and three or four spur roads penetrate the district for 30 or 40 miles. One railroad slashes through it from north to south and two from east to west. Other than that, it is trackless bush, rugged and wild, so broken by lakes and bogs, cliffs, and deep stream gorges that in many areas a man not experienced in the woods could not get through it on foot. It’s among the best hunting country in Ontario, but it’s a tough place to get lost in. Three years in a row a man had died in it.

The fall before Patrick’s death, a hunter had disappeared, a fruitless search was made, and his skeleton was found the next summer, 22 miles from where he was last seen and only 300 yards from a main highway. The year before that there had been another.

There were sportsmen in Sault Ste. Marie who were convinced that better organized searches, carried out promptly by expert bushmen outfitted with adequate equipment, including portable radio sets, might have found the lost men in time, especially in Patrick’s case. In addition, the Algoma country is a famous fishing and boating area, and it had been plagued by drownings that involved long searches, not always successful, for the victims. The need for an effective search-and rescue organization that could bring together specialists in various fields on short notice, utilize their skills to the best advantage, and profit from their know-how and experience, was clearly apparent. The death of Harold Patrick set things in motion.

Among those who believed that more efficient search methods could save lives was Maynard (Mac) McCracken, a lifelong hunter and fisherman thoroughly familiar with the bush and a past president of the Al goma Rod and Gun Club. In the March after Patrick died, he called together 15 men who shared his ideas, and the Sault Search and Rescue Unit was organized, with McCracken as its first president. The 16 charter members who attended that first meeting kicked in $14.50 to start a treasury.

It was a modest beginning, but the backers were men in dead earnest who knew that whenever they were called into action a human life was likely to be at stake. At first there was some mild skepticism on the outside. Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, is a steel-mill city of 45,000 lying across the St. Marys River from its United States counter part, with the Soo locks between them. In a community of that size there were bound to be a few who looked on the new search-and-rescue outfit as a play group for grown men.

The unit didn’t have to wait long to prove itself, however. In the fall of 1959, six months after it was formed, Peter D’Huk, a young German who was in Sault Ste. Marie to study, went deer hunting at Garden Lake, 60 miles to the northeast. Not experienced in the bush and totally unfamiliar with the country, he wandered into a swamp with water on all sides and could not get out. The Search and Rescue Unit was called.

Fifty men were thrown into the search the first day, 75 the second. The third morning, with the situation grow ing more critical, a helicopter was brought in to help, and in midafternoon it found D’Huk. He was brought out in good condition. The unit had shown it meant business and could do the job. Its prestige started to soar and has never dropped.

Today the group is made up of 186 men, chosen from all walks of life and representing a variety of special skills, including steel workers, timber crews, merchants, police officers, and a doctor. Every man is an expert in the bush, trained in rescue-and-survival techniques and able to operate two-way radios. In addition, 22 of the members are aqualung divers, of whom eight have searched for bodies at depths in excess of 100 feet. Some of the best scuba divers in Canada are on the team. The latest increase in the unit’s strength came last November with the addition of the Soo Ski Patrol-two platoons with 32 members, all with special search-and-rescue training.

The organization is chartered as a nonprofit corporation by the Province of Ontario and is subject to standard government requirements and regulations. Five officers direct it. Wilfred Jarrett is president, Bill Kirby and Ivan Shanahan vice presidents, Malcolm (Mac) Nicholson secretary and co ordinator, and Art Kunkel treasurer. Jarrett, Kirby, and Kunkel work at the Algoma Steel Corporation plant, Shanahan is a police sergeant in suburban Tarentorus Township, Nicholson a rate clerk for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

There are no dues and few formalities, but every member has a high sense of responsibility and so far as possible puts search-and-rescue work ahead of everything else. It would be hard to find unpaid volunteers more dedicated.

“Search and rescue is a way of life to every man in the outfit,” Nicholson says. “Most of us are married, and you can imagine what the work imposes on our wives and families at times, but we think it’s worth it.”

The record bears him out. From the time the unit was organized until last fall, it maintained an unbroken record of successful searches. In that period, it brought more than 100 lost men, women, and children out of the bush, or off lakes where they were adrift, with out any loss of life. Forty of the rescues were made in 1963 alone, 11 of them in one 15-day period during moose and deer seasons. In addition, the unit’s divers and other members have recovered the body of every drowning victim, except one, in the Algoma district where they have been called in. Late last November, however, the 100 percent success score ended when young moose hunter Curtis Oliver be came lost less than 50 miles from Sault Ste. Marie. A nine-day search, in which 1,000 men and 14 aircraft took part, failed to find him.

It would be easy to build the unit to two or three times its present size, but the leaders feel the group is about large enough, and membership requirements are purposely kept high. An exception to the amount of personnel in the unit is now being made, however. Nichol son, along with other members of the organization, is attempting to enlist the services of at least two or three men from each of the outlying districts so they will be available for searches in their own areas. “This would be of great value,” says the unit’s coordinator, “because of their familiarity with local terrain.”

Read Next: An Ontario Moose Hunt Turns Into a 10-Day Survival Ordeal, From the Archives

A screening committee investigates every application to the unit and makes a confidential report, and the committee’s word is law. For an organization that collects no dues and pays no wages, it’s an unusually difficult out fit to get into. As a result, coupled with the satisfaction that comes from saving lives, morale is very high, and every search is as organized and disciplined as a military operation.

One of the major problems in the be ginning was the raising of money to purchase and maintain equipment. That’s still a big hurdle, but the unit’s men have done a good job of getting over it. They have raised enough funds to buy more than $20,000 worth of equipment and meet expenses that now run $2,000 to $2,500 a year. Members have sold Christmas trees, sponsored a circus, and resorted to other fund raising plans, but most of the money has come from businessmen in Sault Ste. Marie and surrounding townships, in response to an annual drive, and from the city itself, which now contributes $1,000 a year. Also, wives of unit members are organizing an auxiliary to help raise money. They’ll also lend a hand with the bush cooking on pro longed searches.

Equipment owned by the organization includes a truck with a power winch; an 18-foot boat with a 35-horse power outboard, sonar depth finder, and automatic bailing system; a smaller boat with a 10-h.p. motor; trailers for both; two portable, two-way base radios; several walkie-talkies; two loud hailers; a portable air compressor for refilling aqualung tanks, and a complete base-camp outfit consisting of tents, stoves, and a field kitchen. Recently, the group acquired two flare guns with flares guaranteed to burn out in the air; a huge searchlight, and a vibrator horn with a supposed range of 10 miles. A 10-foot helium balloon with siren attached is in the works.

In addition to the unit’s own equip ment, members supply many major items when needed, including six light trucks and a jeep, all equipped with two-way radios; an additional 11 sets installed in cars; 40 boats, motors, and trailers; canoes, and walkie-talkies. The divers furnish their own suits, air tanks, masks, and other gear. All trucks are equipped for cooking and sleeping and can serve as mobile field bases.

If aircraft are needed, five member owned bush planes are available. If that’s not enough, or if the situation calls for helicopters, the unit can get outside help. It is probably the only civilian outfit in Canada that can call on the United States Air Force when ever the need arises. The U.S.A.F. base at Kincheloe, Michigan, 15 miles away, will put a long-range jet helicopter in the air any time Search and Rescue re quests it, regardless of the fact that the search is to be made in Canada. In turn, the unit keeps six jet fuel dumps scattered in bush locations around the district. The Royal Canadian Air Force has no ‘copters based ill the area, and regular military planes are too fast for efficient searching. To find a lost man, planes must fly low and slowly.

In addition to the co-operation of the U.S.A.F., the U.S. Coast Guard is set to turn out any time Search and Rescue calls on it, in cases of missing boats or marine disasters. And the Algoma Flying Club and Soo Airways make their aircraft available for search work whenever they are needed.

Search and Rescue accepts no pay from those it rescues, regardless of how long or difficult a search may be or how much equipment is used. If a donation is offered, either by the victim or his grateful family, it is turned down with thanks.

The officers are most emphatic on that point. “We were aware when we started out that in many cases the finding of a lost hunter or fisherman, or the recovery of a body, imposes a burden on the person or his family that they can’t afford,” Jarret told me. “No one is to blame. Public agencies often do not have the funds to assign personnel and equipment to such jobs unless they are reimbursed, and flying services and other private businesses can’t be expected to.

“It’s our primary purpose to put prompt and effective search and rescue machinery within the reach of anybody who needs it, regardless of his circumstances. If we made a charge or accepted a reward, the story would soon get around that our services are only for those who can afford to pay for them, and we’d be defeating that purpose. Whatever we do for anybody in trouble is gratis, and it must stay that way.”

Encouraged by the success of the Sault unit, and with its help, outdoors men in the nearby towns of Blind River, Elliott Lake, and Wawa have formed similar groups on a smaller scale. It’s a plan sportsmen could put into effect in wild country almost anywhere in the northern United States or Canada, the backers believe, and the Sault organization stands ready to advise and help any interested group.

On the average, Search and Rescue is called on about 30 times a year, and the requests for help cover a wide range of emergencies. The unit has looked for stolen boats, recovered bodies following a steel-mill explosion, rescued the victim of a shooting accident, checked unoccupied camps for escaped convicts, and brought out of the bush a man whose hip was broken when a tractor overturned on him at a camp two miles from the nearest road.

Now and then, for a change, a call comes in that is considered amusing.

In one case, a search party located a “lost” man who had taken to the bush and disappeared deliberately to avoid the service of a subpoena. And there is one hunter who has been lost and found three times. He has been warned unofficially that if it happens again he can expect a punch in the nose.

The unit is divided into squads of eight to 42 men, each under a squad leader. At present there are four bush squads, two diving squads whose major work is the recovery of drowning victims, a drag squad that shares this job, a communications squad for the upkeep and maintenance of radio equipment, a first-aid squad headed by a St. John Ambulance Brigade man with special training, and a utility squad capable of filling in where needed.

Most calls come from the police, to whom reports of accidents or disasters are made originally. As unit coordinator, Nicholson’s phone number is listed with Mountie and Ontario Provincial Police posts and with city and township police departments through out the area. The bulk of the requests for help go direct to him. He maintains an office in his home to keep the unit’s records and handle its work. This office is equipped with two-way radio, large scale maps of the entire Algoma district, and charts of Lake Superior and the St. Marys River. He or his wife do their best to be available to the phone 24 hours a day.

Unless a situation requires immediate action, Nicholson goes first to the scene with an assistant, tries to find out what’s happened, sizes things up, and decides what kind of operation is needed. He then notifies his squad lead ers, and they, in turn, call out their men. In case of a lengthy search, base camp is set up in the field and the operation directed from there by radio. If more men or relief crews are needed, they are called the same way. Usually a police officer stays at the base camp until the search ends.

Dogs are being used more and more in search-and-rescue work in many places, and one of the most valued helpers the Sault unit has is a big Labrador, specially trained for the job, belonging to Nicholson. He does not run a track as a hound would, but follows body scent on trees and under growth. He has worked out trails 48 hours old.

In addition, several members of the Algoma Retriever Association belong to the Search and Rescue Unit, and a number of their dogs are now being trained for search operations. Also, the sheriff of Dickinson County, at Iron Mountain on the Michigan-Wisconsin border 225 miles west of Sault Ste. Marie, stands ready to send in two trained bloodhounds any time the need arises. They could be flown to the Soo and be at the scene of a search in a few hours.

No search is started for lost persons until daylight ( such occurrences are most commonly reported in the evening or during the night), with one exception. In the case of missing children, the rescue operation begins instantly, day or night. The value of that rule has been proved many times.

In January, 1960, less than a year after the unit was organized, Sergeant Shanahan, on duty at his police head quarters, took a frantic call about 5 :30 on a cold, snowy afternoon. Two young children were lost. They were John and Denise Brisson, two and four years old, youngsters of a family living in Shanahan’s home township.

There were a number of new houses under construction in the neighborhood, and Shanahan checked them first. He found nothing, however, and as dark ness fell he decided the job was one for Search and Rescue. Within 30 minutes a crew of 75 men was combing the swampy bush beyond the housing area. It was only a few degrees above zero, with heavy snow falling, and though the two youngsters were warmly dressed, the searchers knew there was no time to lose. They moved in a line from one road to the next, only a few steps apart, probing with lights, stopping frequently to call the children by name, but they were too scared to reply.

It took the search crew only an hour to do the job. The end man on the line saw a small, trampled place in the snow, and then his light picked out Denise and John, huddled under a spruce tree, wet and shaking with cold. Veteran searchers agreed it would have been too late by morning to find them alive.

The imperative need for prompt search for children was demonstrated again in May, 1961. On a cold, cloudy evening the Ontario Provincial Police post at the Soo received a report that two brothers, Ian and Francis Mallisewski, six and nine years old, were missing at the hamlet of Echo Bay, at the head of Lake George, a big widen ing of the north channel of the St. Marys 15 miles downriver from Sault Ste. Marie. The police called Search and Rescue.

At first no one knew if the boys had wandered away in the bush, had drowned, or were adrift on the lake. Then somebody reported having seen the two brothers fishing that afternoon from the stern of an old leaky boat tied to shore at the mouth of the Echo River. The boat was missing, so the rescue crew decided on a water search. It paid off. The boys, as they related later, had climbed into the boat, pushed it out as far as the rope permitted, and the rope had come untied, setting them adrift. They were beyond reach of shore before they realized what was happening, and the wind carried them out into the open lake with no equip ment but two bailing cans.

Lake George is 12 miles long and four to five wide, big enough to be dangerous in rough weather. And bad weather was making up that night, with fog so thick a small boat could not be seen 100 feet away.

The Search and Rescue Unit’s boats groped through the fog, taking the direction of the afternoon wind into ac count. The men stopped often, cutting their motors, shouting, and listening. After midnight, one crew heard a faint reply coming out of the murk. They rowed ahead, heard a louder cry, and then the old boat loomed up in the fog, two miles offshore and four from where it had gone adrift. Ian and Francis had lost one bailing can and there was four inches of water in the boat. An hour later a hard thunderstorm swept across the lake, with high winds and a wild downpour of rain. Had the search been delayed until daylight, it would have turned up only a swamped boat.

here has been only one really long search for a lost hunter or fisher man since the unit was formed, the one mentioned earlier that ended in tragic disappointment last fall. All the others have been brief, thanks in large degree to effective methods. But good organization, efficiency, aircraft, and radio equipment availed nothing last November when Curtis Oliver, a 22-year-old steel worker from Sault Ste. Marie, went into the bush at Deil Lake by himself and failed to come out.

A road runs to Devil Lake from Glendale, 30 miles northeast of the Soo, and Oliver’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Harold Oliver, had a camp there. The country beyond is roadless and as rough as any in the Algoma district. Nobody knew exactly in which direction the young moose hunter had gone. On the day he disappeared, cold rain fell for hours, turning to snow, and the temperature that night fell to zero.

Searchers, based at the Oliver camp, later found mute evidence of what had befallen him. Following his tracks, they came on the place where he had tried in vain to start a fire. Eighteen wet matches lay on the ground.

A quarter of a mile farther on, the boy had torn off evergreen branches with his bare hands in an effort to build a shelter. Then, leaving that spot, he had tried to burrow under a log to get some refuge from the bitter cold.

The search crews believe that at that point his hands were frozen, for he had tried to peel the wrapper off a chocolate bar, failed, eaten a few bites, paper and all, and discarded the rest. There the trail ended. When nine days of desperate search, one of the biggest operations of its kind ever carried out in Ontario, failed to turn up any further trace of the lost man, and there no longer remained any hope that he was alive, the Search and Rescue Unit reluctantly called quits.

“The country was so bad we were risking the lives of our searchers,” Nicholson comments. “There was no point in that once we were sure the lost man could not possibly have survived.” One of the biggest searches the unit had made prior to that one, and one that caused a great deal of concern for a short time, had an unexpectedly happy ending and also points a moral.

On a Tuesday morning in May, 1963, two Sault Ste. Marie steel workers drove north up Highway 17 on a fish ing trip. They left their truck at the mouth of the Coldwater River, 120 miles from the Soo, put their canoe in, and vanished.

They were due back home on Thursday night. A few hours of delay caused no grave concern, but when Friday passed with no word from them, their families called Search and Rescue.

Nicholson took a small crew to the mouth of the Coldwater that night and found the truck but nothing else. Re turning to Sault Ste. Marie at 6 a.m., he ordered a full-scale search. At 8: 30, five trucks and two cars were on the way with 21 of the unit’s men, nine Mounties, and two boats.

A field base was set up at the scene, and an aircraft was called in to search the Lake Superior shore. The boats and foot parties also patrolled the beach and shoreline in both directions from the river’s mouth. The Coldwater was too fast and rough for the fisher men to have gone upstream by canoe. The search continued the rest of Saturday, but when darkness fell the canoe had not been found. Shortly after day light on Sunday morning, however, the missing men walked out to the road, safe and well. They had hiked inland to fish, hiding their canoe under brush on the beach, had become confused. and had difficulty finding their way out.

Relating that incident, Nicholson winds up with a sharp warning. “Any time you’re heading into the bush, be sure somebody knows your plans, where you intend to go, and what you intend to do,” he urges. “Searching for a lost man is a lot easier, and he is far more likely to be found, if the search party knows where to look.”

Some of the toughest assignments the unit has taken on have been searches for drowned persons. There is less suspense in an effort of that kind than in looking for a lost hunter or fisherman. The victim is already beyond help, and no race against time is involved. Nevertheless, diving for a body in cold, murky water ( many of the drowning searches have been made in late fall, when ice was forming), sometimes in almost bottomless mud, sometimes on bottoms paved with rocks or sunken logs, is a hard and lonely job. One of the longest and most difficult searches the unit has ever taken part in was for two drowning victims in November, 1961. It was an operation that lasted a week and involved 200 men, 72 boats, two planes, and a helicopter, and it took place on a lake 185 miles from Sault Ste. Marie.

The two men failed to return home from a weekend moose hunt in the Hammer Lake country south of the town of White River, and Search and Rescue was called out. On Tuesday morning, a plane spotted the hunters’ overturned canoe on the lake, and later their paddles were found. Search of shore and islands revealed no trace of the men, and there was little question they had drowned.

The unit set up its field base. Off duty searchers and spectators huddled around campfires on shore while dragging crews swept back and forth

across the water, hampered by high winds and driving snow. The lake bot tom was too rocky for dragging, how ever. Fourteen of the unit’s ace divers, working in relays in the bitterly cold water at depths up to 50 feet, finally found the bodies and brought them up. Another difficult assignment had been carried out by divers from the unit in May of that same year, when two fishermen from Michigan drowned in Clear Lake north of Thessalon. Fourteen men took part in a five-day search that time. Sergeant Shanahan and Karl Faldien made the recovery, diving for the second victim in 110 feet of water. Shanahan’s only comment today is that the lake is badly misnamed.

Those who have taken part in search operations agree that, while a hunt for lost children involves desperate urgency and worry, in one way it is preferable to looking for grown-ups.

Youngsters rarely panic or travel far. Usually they wander a short distance, become tired, give up, and lie down. That means a short search. For example, the Sault unit found a 3½ year-old girl, reported missing from her rural home at 9 p.m. one evening last July, in just 15 minutes, using a crew of 14 men.

On the other hand, the men in a bush search for a grown-up always confront the strong possibility that the lost per son will fall victim to blind fright and lose all reason. When that happens, no two people behave alike, and there is no rhyme or reason for what they do.

Last November, after a search for a 24-year-old deer hunter in the Wabos area 30 miles northeast of Sault fte. Marie had lasted some 36 hours, the search party located the lost man with loud hailers. He replied to the hails with rifle shots, and later very faint shouts could be heard from him.

e was located during the night, however, and since the country was extremely difficult to get through, it was decided to wait until daybreak be fore trying to reach him. Sometime be fore daylight, he panicked and started to travel. It required 11 more hours to find him, nine miles from where the

searchers had first made contact.

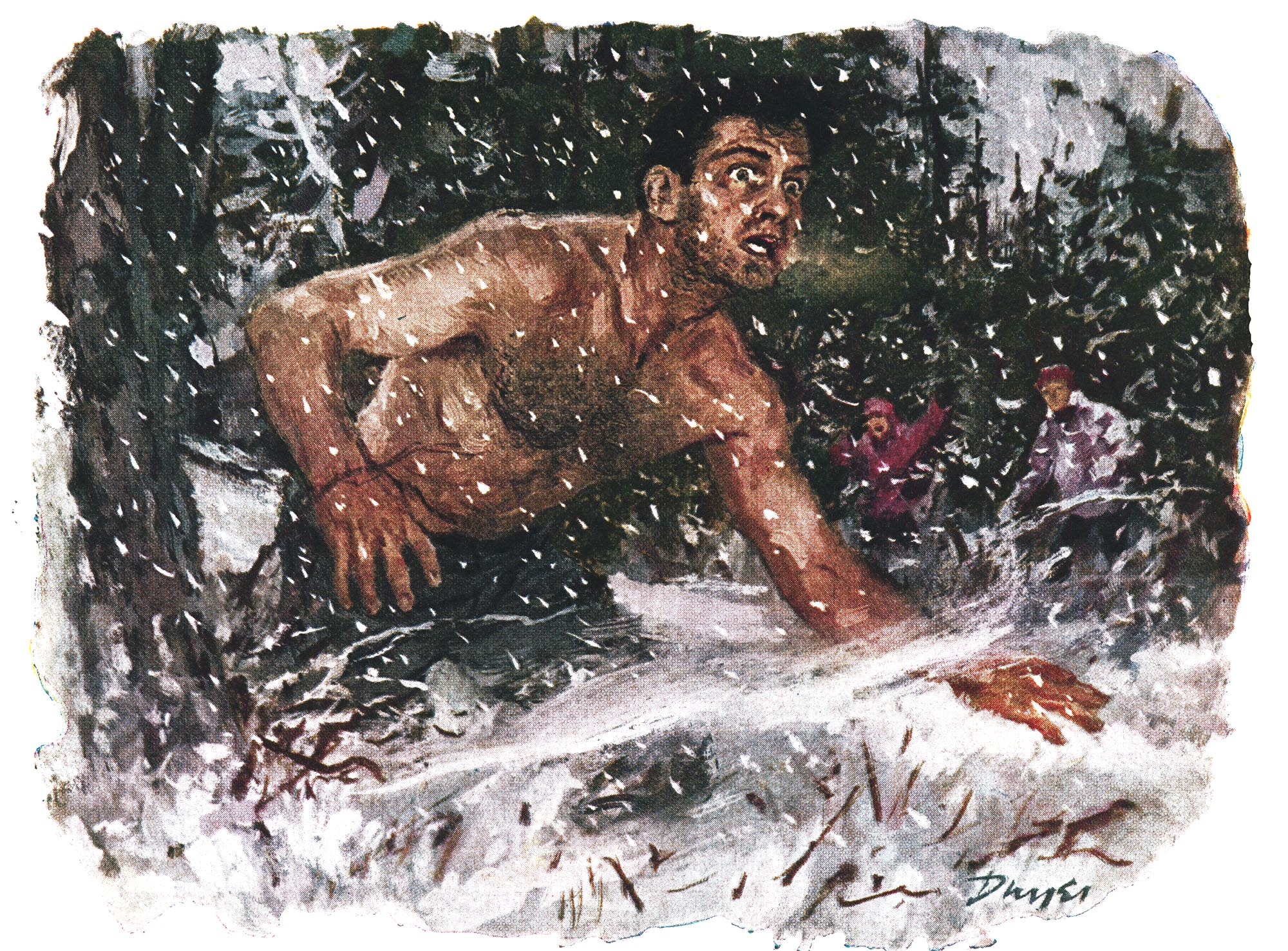

A more incredible example happened at Wawa, 150 miles north of Sault Ste. Marie on Highway 17, the year before. A moose hunter went astray in late November in some of the roughest country in Ontario. He was warmly dressed, carried matches, a rifle, and plenty of ammunition. He could have made a fire and survived a week or more without much difficulty. When searchers from the Wawa unit found him he was 30 miles from his starting point, the rifle had been thrown away, and he was wandering the snowy bush naked to the waist.

It’s because of incidents like this that the Sault unit operates on the theory that any time a search for a lost man lasts three days it has become a life-and-death affair. It’s a matter of pride with every man in the outfit that since the unit was formed, with the exception of the Oliver tragedy, only has no search for a living person failed, but none has gone beyond that critical 72-hour period.

Read Next: Our Professor Gives Extra Credit for Catching Live Rattlesnakes

“The shorter the search, the better,” Nicholson puts it. “We’re organized to start promptly and finish as quickly as we can.”

The unit’s record for effective and responsible operation is mirrored now in tremendous public confidence and re spect. “There’s no one and no organization in the community that won’t turn out if Search and Rescue calls on ’em,” a Sault businessman told me last fall. And a grizzled moose hunter added, “If I had to be lost anywhere in Canada, I’d want it to be here in the Algoma district. If these search crews can’t find you, you’re not going to be found.”

Read the full article here