This story “The Alann Steen Story: How I Survived,” appeared in the January 1993 print issue of Outdoor Life. Steen, who served as a U.S. Marine for six years and was briefly deployed during the Cuban Missile Crisis, died from cancer in 2018 at the age of 79. This editor’s note accompanied the original story:

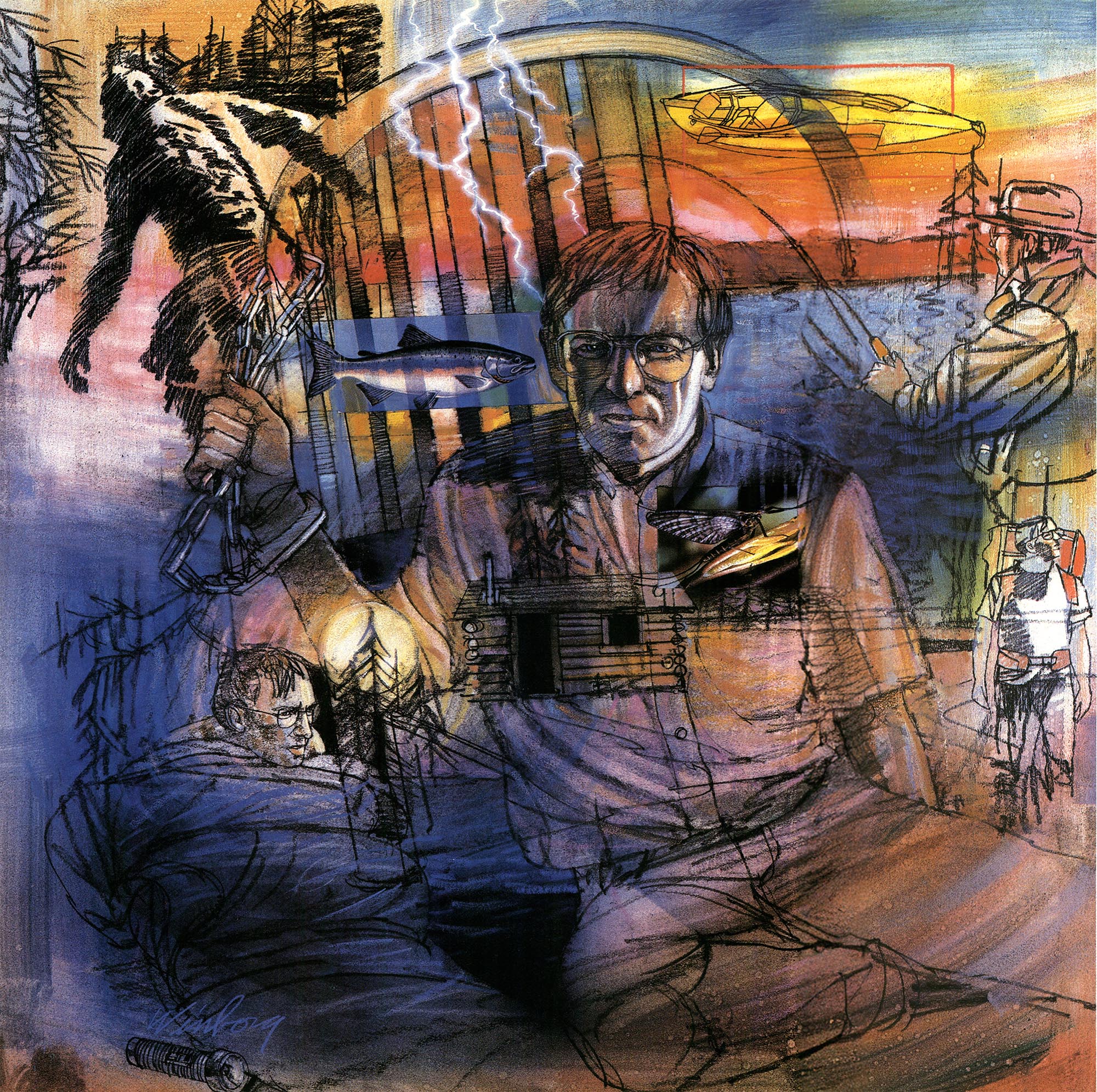

Held captive in Lebanon, Alann Steen faced the reality of a cold cell and iron chains, the terror of a city exploding with mortar rounds and gunfire. But Steen had known fear before. In 1979, he wrote a story for Outdoor Life about his solo kayaking trip down a river in the Yukon. In the story, “Grizzly In No-Mans Land,” Steen faces a large bear: “Never had I experienced fear as I experienced it that day. Nor had I felt so helpless, cold and alone.” Steen’s words foreshadowed the chilling events that would change his life forever. While a professor at Beirut University in Lebanon, Steen was abducted by terrorists and held captive for five years. After Steen’s release in 1991, [then] Editor-in-Chief Vin Sparano contacted him. Over the phone, Steen described the strength he found in remembering his times outdoors. This is his exclusive story.

It had started as a puffy dark cloud surrounded by the Yukon’s tundra and the late summer’s mixture of sundown-sunrise, twilight-dawn — you know, when the sun sinks just below the horizon for a couple of hours, keeping the sky ablaze. Within what seemed seconds the cloud stretched out, west to east, and I told myself this was not possible; I mean, nothing moves that quickly. But this was the Yukon, 50 miles above the Arctic Circle. Maybe such things avail themselves to people who seek escape … and find it.

Behind me was an abandoned trapper’s cabin, so well-built that I could smell maybe 60 years of muskrat lure that wafted from its open door. Before me was my Folbot kayak, a yellow spearhead against the muddy Porcupine River. A family of mallards swam around the back of the craft, effortlessly with and against the current. The Porcupine flowed eastward here, but in time would turn north toward the village of Old Crow, where the only migrants expected were caribou. The Porcupine would swing to the southwest near there and head for its meeting with the Yukon River and ultimately the Bering Sea.

Suddenly, the cloud was above me, dulling even more of the Porcupine’s brown surface. Bold lightning sprang down from the cloud, yet the thunder came to me muted. Thin lightning streaks came down upon the river and skated on its surface for a few moments before disappearing. Then, as if Thor himself had turned up the volume, came the crack of thunder. Thunder then lightning, thunder then lightning, thunder then lightning. Even in the Yukon I knew this wasn’t possible.

I awoke and sat up, the heavy chain on my wrist dragging the headboard of the child’s bed Dr. Jon Turner and I had occupied for the past couple of days. Jon sat on the floor, his head between his knees. Beside another bed Robert Polhill played solitaire with a deck of timeworn cards. Between them lay Dr. Mitheleshvar Singh, snoring loudly, extremely loudly, almost without interruption. I looked at Dr. Singh, then at Robert. He smiled and shook his head.

“Mortar,” he said. “They’re still trying to knock out that machine gun,” nodding toward the big open window covered with a thin cotton blanket. Outside, from what little we could see, we were separated from the machine-gunner by a high white wall, perhaps 10 feet away and unmarked except for its cratered top. The gunner was always changing his position, while the mortar crew fired blindly.

The gunner opened up again, firing heaven knows where, but so close we could hear him grunting between bursts. When he quit, a masked guard appeared in the doorway of our tiny room. “You like Lebanon?” he asked. “Maybe you will stay.” He added that we “will not be afraid.” When he disappeared, the gunner resumed.

A moment later a mortar shell exploded on our side of the wall, blowing in the blanket and sending in dirt and small rocks. Through the now-exposed window opening we could see half an orange tree, a fish pond filled with mud, and a wall that was no longer white. If we had our choice, we would’ve all scampered for shelter. But being chained to the floor or to a bed, this was not possible.

The date was sometime in June 1988. We had been hostages in Lebanon for 17 months, yet the question that still ran through our minds was, “Why?” But, heck, we knew why. Some fanatical followers of the Ayatollah Khomeini, posing as intelligence agents of the Lebanese Army, pulled off a most-brilliant ruse, leaving the dean and the head of security of Beirut University College gaping like a pair of largemouth bass, and four professors fastened to a chain stringer like so many suckers.

Yet for all our captors’ efforts we knew they wouldn’t succeed. Their demands of freedom for 400 Palestinian fighters held in Israeli prisons in exchange for our release would be ignored; the United States makes no concessions to terrorists.

Meanwhile the firefight intensified. We could hear automatic-weapon fire and large explosions less than a block away, as well as rockets overhead, heading for somewhere. One of the guards had told us a few days before that this was nothing more than a squabble between two families, over money. “Using tanks and heavy artillery?” I thought. We were frightened — at least I was — and not to show it I wanted to be alone. And to be elsewhere.

Everyone has to be alone, at least for a while. For some it might be a special room for an hour, a favorite fishing spot for a day. But there are those who need solitude for a longer time — the sailor who chases the sun around the world in a small boat, or the trapper who watches alone the northern lights through a Klondike winter. Then there are the Walter Mittys and the meditators who can enter their own special worlds for a minute or two and return to this one, refreshed. I envy them.

As hostages, this wasn’t the first time we were exposed to such fighting, nor would it be the last. Like the Lebanese, we never got used to it, and the fear never went away. We were allowed little cooling in summer and little warmth in winter. Soon, from October 1988 to February 1990, we would find our food rations cut to sometimes less than 500 calories a day. And because I wanted freedom, essentially through escape, and my comrades thought it wiser to wait out the ordeal, I often found myself quite alone, awaiting the chance.

In the year since my release in December 1991, people have asked me how I coped. Hope, patience and anger, I’ve answered. But I didn’t want to just cope; I wanted to survive, to come out whole, the same man I was. To do so, I used solitude to combat loneliness and boredom. I also found myself equating the situation we faced at the time to experiences I had encountered before, in the outdoors, in some wilderness or upon some river. It seemed so long ago, but because I found it helped me, I often shared the experiences with Jon, Robert and Dr. Singh:

“Wet!” I said. “You call this wet?”

We were held in a place we called the “second dungeon,” where our mattresses were sucking moisture from the floor and the walls were black with mildew. “I once backpacked for three days a stretch of the California coast north of Shelter Cove where if it wasn’t raining, it was caked in fog. Its fickle surf and tides allowed me to pass only when they wanted me to pass, but they never allowed me to dry …. “

At other times I tried to explain fright, self-seclusion and loneliness in the Yukon. I relived the eeriness of a hot night in the Yolla Bolly Wilderness in July and the frigid freshness of the Marble Mountains in May.

On the day of the machine gun vs. the mortar I told another tale, of my night with Sasquatch and the “little people.”

“They aren’t a legend,” I said, hoping for some response. Robert, an agnostic, was reading a condensed version of the New Testament. Dr. Singh was now playing solitaire. Jon, I knew, was thinking about his daughter; she would be 1 year old that month.

“Sasquatch is another name for Bigfoot,” Jon answered. Jon was from Idaho; he would know.

“Yes. Sasquatch is Bigfoot,” I said, easing myself onto my skimpy pillow and looking up at a water-stained ceiling, recalling all of the story but probably retelling only parts. Outside, there was a break in the action. Perhaps recalling the story could arrest my fear from the battle waiting to recur.

“It all happened in the fall of 1982,” I began, “but it wouldn’t have happened at all had I not talked to Rudolph Socktish, the religious leader of the Hupa Indians, and Jimmy Jackson, a member of the tribal council, 11 years before. And I wouldn’t have talked to them had I not tried to paddle an inflatable kayak on the Trinity River from somewhere below Cedar Falls in western Trinity County, California.”

I had planned to paddle through a good part of Humboldt County — to Weitchpec, where the Trinity meets the Klamath River, and then on the Klamath to the sea, a total distance of about 90 miles. Unfortunately, the Trinity was unaccommodating to inflatable kayaks that day. Its white water and unavoidable funnels and hidden rocks flipped the kayak — and me — a dozen times before I traveled a dozen miles. It 67 soaked my equipment and ruined my food as well as a fine old camera.

“It was exhilarating … almost fun,” I whispered, raising my arms, the chain clinking on the headboard. “But it was also continued apprehension and out-and-out fear — so much so that I called it quits somewhere on the Hupa Reservation, about 10 miles south of the Klamath.”

When I had climbed up the bank there stood Socktish and Jackson. As editor of a local newspaper, I had met and interviewed Socktish a couple of times before.

As religious leader, Socktish was essentially the “chief” of the Hupas, though they have no such title. He noticed the bruises on my arms and face. “If the sweathouse were hot today, it would help you,” he said, and nodded toward a sunken structure covered by cedar or redwood. “We Hupas use it to cleanse and cure ourselves, both physically and spiritually.”

Jackson took me down through a small doorway into a large room with an earthen floor. It was cool and empty, filled only with a smell of ashes. When we climbed out, Socktish was gone.

“We also use the sweathouse to lose our human scent,” Jackson said. “But it often takes days to do so.”

“It must be quite an advantage for the hunter,” I said.

He said it was, but added that the Hupas also lose their scent so they may see Sasquatch and the “little people.” I almost made some inane remark, but I noticed in time that he was quite serious. Of course, I had heard of Sasquatch, the huge manlike creature that supposedly roams the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. But the “little people?”

“They look like you and me, but maybe only knee high,” Jackson said.

“Like leprechauns,” I offered.

“Yes, like leprechauns,” he answered. “But they wear no clothes, come out at dusk, and are seen only by those who carry no scent.”

Why was he so serious? I asked him if anyone had brought one back. He said those who had tried had come back half crazed.

“Have you ever seen Sasquatch?” I asked. “The little people?”

“They’re not legend,” he answered.

I looked over the bed and found my three colleagues half asleep. I wasn’t offended. It had been a bad day; it still wasn’t over. And, you see, talking about this experience might have been a mental escape. On the other hand, because I had attempted two physical escapes and failed, reliving an adventure of pure freedom might’ve been therapy. Of course, where talking can bring on exaggerations, remembering can be sprinkled with what-ifs. For 11 years Jackson’s words, his sincerity, had intrigued me, and the night I sought the truth left my memory loaded with questions — and possibilities:

I had been king salmon fishing on the Salmon River 70 miles northeast of Eureka. A few hours before, a 60-pound king salmon had hit a silver spoon and fought like nothing I had ever experienced before. Okay, maybe it weighed less than 30 pounds, but the point was moot. I lost the fish two feet from shore mainly because the friend who was to bring the auxiliary equipment — the net, waders and so on — never showed up.

Still, I was excited. For all the years I lived in northern California this would have been my first king salmon. But that was the limit of my luck. By sundown it was evident they’d rather spawn than take my spoon, and I reeled in my last cast.

As the Salmon River was greatly placer mined, leaving nothing for a bank but a lot of bedrock, I hiked in about 200 feet and found a soft, sheltered spot. About 20 yards beyond was a shallow pool of smelly, stagnant water surrounded by mud. What a thing to fall into, I thought. I ate a cold meal, and had all the intentions in the world to get some sleep when Jimmy Jackson’s words about Sasquatch, and the little people, and no human scent came to mind. I looked at that stagnant pool.

What would the world think of me, a 43-year-old journalism professor, rolling nude in stagnant water to test a theory that its stink might hide my scent so I might see creatures that probably didn’t even exist? Well, I figured, Mt. Shasta, the supposed home of Sasquatch, is about 60 miles to the northeast. Weak reasoning to be sure. Sasquatch, even if it indeed was not only legend, might be anywhere in a million square miles. And as for the little people …

So maybe I was crazy. But everything would be all right if the world never found out. My pack thermometer read 50°, and I began unbuttoning my shirt.

The silty water had dried to a thin crust by the time I wrapped myself in my sleeping bag and prepared to wait. There might have been a little silver left in the Western sky by then, but in time the only light came from the stars; my field of vision in front was 10 yards, maybe 15. I dozed off a couple of times with, I think, the stench under my nose jerking me awake.

It was during one of those times that I heard them — whispers or grunts and maybe squeals or giggles, like people who were trying to be quiet, but not caring if they weren’t.

They were coming toward me from the left side of the pool, as if they knew it was there; they were walking on rock and gravel, but it sounded more like, well, chewing. I strained to hear voices, but discerned nothing. When they were almost directly on my left, I figured they were less than 50 feet away. I reached for my flashlight.

And I froze. With my thumb on the switch I just couldn’t turn it on. Of course what I heard were deer, and a few seconds of light would set my mind at ease; I was crazy not to. But what would happen if they were something else? My thumb quivered on the button, yet received no command to push. A moment later the sounds had moved behind me, heading for the river. I had had my chance and blew it, the victim of a dark night and an overactive imagination.

I rolled over the bed. “I looked at the whole episode as an unbelievable gift to be guarded and never told,” I said. “But there’s nothing to lose by telling of it now. …”

Read Next: Frozen Terror, One of the Greatest Survival Stories of All Time

It was almost dark and I could see the flashes of some battle being fought somewhere in the city. I lay back on my pillow and let myself see the trapper’s cabin for the last time, as I let the kayak drift backward into the Porcupine’s current. I remembered young mallards swimming near shore, trying to keep pace but failing as the current took its grip. In a moment I knew a mayfly would land on the water’s surface, then suddenly disappear in a ripple. Instead a mortar shell landed nearby and the whole scene disappeared in a moment.”

Read the full article here