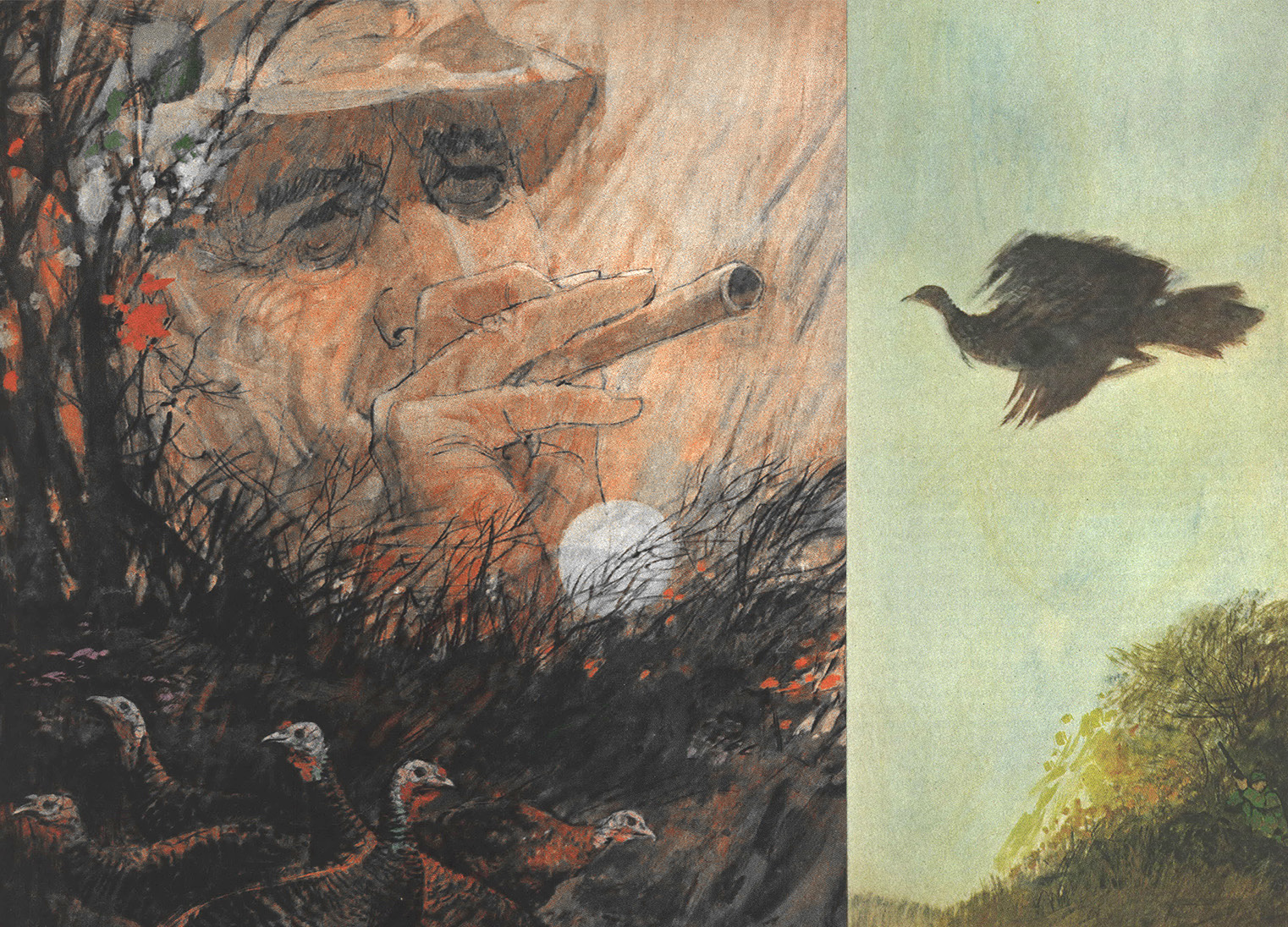

This story, “Longbeard Lives,” appeared in the March 1972 issue of Outdoor Life.

The hunt was over, or we thought it was. It was the last day of the spring gobbler season. We had come out of the woods and were relaxing in camp. My son Brownie and my brother Samson were washing the dishes. My grandson Bradley was still sitting at the table gazing out of the window and thinking whatever a 16-year-old thinks about when a hunt ends. I was lying on the top bunk almost asleep.

Suddenly Bradley called out: “A turkey! A big turkey!”

Brownie looked out the same window.

“It’s Ranger!” he exclaimed. “Old gobbler Ranger!”

“It’s The Phantom,” brother Samson said.

By then I was off the bunk. I wanted to know if a turkey really was to be seen through the window. Sure enough, coming right toward camp was the big gobbler I had named Longbeard.

“Get him quick, boys,” I said. adding to the bedlam. “It’s Longbeard ! He’s making fun of us because we couldn’t find him.”

We had all seen the old gobbler many times, and we had different names for him. To Bradley, he was just a big turkey. To Brownie, he was Old Ranger because he always turned up where least expected. Samson called him The Phantom because of his ghostlike appearances and disappearances.

I called him Longbeard because I am a collector of gobbler beards. I have a collection any gobbler hunter would envy. Among them is one 13 inches long that was mentioned in the December 1941 issue of OUTDOOR LIFE. At that time, P. A. Parsons, who then wrote the regular column “All Over the Map,” said: “C. D. Sions, Petersburg, W. Va., seeing mention of a 12½-inch Oklahoma turkey beard in this department, had local game warden Harrison Shobe measure one from a turkey he killed in 1939. It was 13 inches, and this will be the record until we hear of a longer one.”

Well, so far, no one seems to have heard of a longer one, so I guess I still have something of a record, though no one keeps formal records of gobbler beards in the way records of North American big-game trophies are kept by the Boone and Crockett Club. To a lot of hunters, the gobbler turkey is the biggest of big game, and maybe someone should hold competitions and keep formal records.

All of my hunting buddies, especially my son, would like to kill a gobbler with a longer beard. Like most sportsmen, I’d like to do better myself. We had all seen the big gobbler often enough to believe that he had a real trophy of a beard. Brownie first noticed that long beard one day when he and his wife were squirrel hunting.

“Dad,” he said to me later, “I saw a gobbler with a beard that I think sure would beat your thirteen-incher. One of us must get that old gobbler.”

We have been after him ever since. In fact, we bought the mountain so that we could propagate his kind and protect him and his relations from out-of-season poachers. I have some experience along those lines. I’ve raised and released from 10 to 20 turkeys of the wild breed every year for over 20 years, and I often put out feed for the birds. I also worked two years as educational advisor to the director of the West Virginia Conservation Commission.

The members of our hunting gang are: James Paul (Buck) Geary, an attorney in Petersburg, West Virginia; Robert (Bob) Harper, farmer, politician, and businessman in Moorefield, West Virginia; my brother Samson, a retired insurance man from Hagerstown, Maryland; my son Brownie, manager of the Petersburg Southern States Store; and myself, the retired superintendent of Grant County Schools.

We bought 711 acres of choice mountain land near Moorefield, West Virginia to provide good hunting for ourselves and our friends. We formed a corporation to own the land and call ourselves the 7-11 Club because we have 711 acres. The $24,000 was a big price to pay, but we tried to tell ourselves, and we believe we convinced our wives, that we bought the mountain and not just the right to hunt Longbeard.

This old gobbler made fools of all of us. He won every trick both spring and fall for two years, and don’t for one minute think he was up against amateurs.

I first got a good look at the big gobbler during deer season. He and two other gobblers walked up to within 100 yards of me. His size impressed me as much as his long beard. The other gobblers flew first. He stood there as though he wanted me to take a good look at him. He sure acted as though he knew turkey season was out. I noticed again that he was bigger than other turkeys that winter when I was feeding some wild turkeys.

This old gobbler made fools of all of us. He won every trick both spring and fall for two years, and don’t for one minute think he was up against amateurs. The boys I hunt with are tops. Some have graduated from turkey hunters to gobbler hunters, and we all get our game every year. My son and I together have a collection of 62 wild-gobbler beards.

Let me give you some examples of how that old bird has made monkeys out of my gang and me. One fall I went to the woods long before the season came in. I found where some old gobblers roosted, where they watered, and where they fed. I also found where a lone gobbler had been feeding under some grapevines. I suspected he was the big gobbler I had named Longbeard.

I waited for him the first morning of turkey season. He didn’t come, and I froze out. Just as I rose to leave, he flew from under the hill out of shotgun range. Did he know I was there? I didn’t think so then. I waited several more times. He didn’t come back.

The next fall I was determined to get old Longbeard or know the reason why. I didn’t do either. Twice, I almost got him. Or so I thought.

Snow was on the ground the first time. That has always been the best time to get an old gobbler, if you know how. I know how to get an ordinary gobbler, but Longbeard wasn’t ordinary. On this snowy morning I had begun to think of him only as a lucky gobbler, not a wise one.

Related: The Best Turkey Calls of 2025, Tested and Reviewed

He was living up to the Old Ranger name that Brownie had given him and was always where I would least expect him to be. He was with a flock of wild turkeys. Old gobblers usually stay near but not with the flock. We soon scattered the flock, and I singled out the biggest track, which I suspected to be Longbeard’s, and followed.

The side of the mountain there is terraced in a series of narrow flats and short steep slopes. I tracked old Longbeard down the mountain, and as I came to each drop-off, I crept up to peek over onto the flat below. I studied this one flat very carefully for a long time. An experienced gobbler hunter never hurries. Patience is as important as skill. I could see all of the flat except a very small part right close under the drop-off. I knew he could be there, so I listened but heard no scratching. When I was sure he had gone over the next slope farther down the mountain, I lowered my 12 gauge Remington pump and started over the edge.

Right there below me and within easy shotgun range were three old gobblers. Maybe it was gobbler ague, but whatever excuse I might offer, it’s a fact that all three went over the abrupt drop and out of sight before I could even decide which one was Longbeard. Men who hunt this big dark bird know how it can sometimes vanish on foot quicker than on the wing.

Later the same fall, I went with Bob Harper, who had paid his share of the $24,000 for Longbeard’s mountain home, to see if luck would change in our favor. We were standing on a ridge planning our day’s hunt.

“I see a turkey on the next ridge,” Bob said.

Then we saw a second and larger gobbler walking over the ridge, apparently unalarmed. That one, we rightly surmised, was Longbeard, but we came up with a plan for an ordinary gobbler. I went down the hollow and came up on the opposite side of the big turkey. Bob was to ease very slowly over between the two gobblers

Did it work? It sure did — for Longbeard, but not for us. When we closed in, he flushed 50 yards away, down the ridge just out of range.

I next saw Longbeard on the last day of the following spring season, and I described how he came into our camp at the beginning of this story. Brownie and Bob both grabbed their shotguns and slipped out the door, but Longbeard went over the brow of the mountain at exactly the right moment. We have spent a great deal of time and talk since then wondering why he came to camp. We’ll never know, but we have our suspicions.

When I was sure he had gone over the next slope farther down the mountain, I lowered my 12 gauge Remington pump and started over the edge.

The fall-season opener found me hidden exactly where we had last seen Longbeard. My friendly feelings by then had changed to those of a jilted suitor who wants just one more date. It was a long day. I shifted parts of my anatomy many times but kept the same spot of ground warm all day. While I waited and wondered, the sun went down.

As I watched the red glow in the west, I thought, It’s over for today — the turkeys will soon be flying to roost. I really felt that it was foolish to wait any longer, but I believe that as long as there’s light, there’s hope. And it was still light — plenty light enough to see two large turkeys appear on the ridge above me.

The gobblers started off toward the steeper side of the mountain and were passing well out of range. I had but one chance. I had to risk a call. I did, and one of the big turkeys answered. Then he left the other gobbler and came straight toward me. I knew he was an old gobbler, but in the fast-fading light, I couldn’t tell whether he was Longbeard or not. Then I saw his beard and knew he wasn’t, and I was suddenly glad. Maybe I would get that gobbler, and Longbeard would still be there for future seasons. When the turkey was well within range, I collected my reward for the long wait.

Then I had another surprise. Before I picked up my turkey, I saw the short red legs without spurs that mean a hen and not a gobbler. How could it have happened? Had I imagined seeing a beard ? I turned the turkey over, and there was the beard. For the third time in my life I had killed an old hen with a beard. It is very rare for a wild turkey hen to have a beard, but it does happen. My hunting for the season was over. If Longbeard’s life was to end that season, someone else would take it.

Then deer season came in. I was on a stand at the far western end of our land one evening when I heard what I thought and hoped were deer. Then I could distinguish the step-by-step sound of two-legged creatures instead of the rustle of four-footed animals. When they stepped out, I saw two big tom turkeys. I couldn’t see their beards, but I felt sure from his size and actions, that the larger one was Longbeard.

I saw Longbeard again on the Sunday before the next spring gobbler season opened. Sunday evening after camp was arranged, I announced that I was going out to shoot Longbeard.

“Are you taking your gun?” Brownie asked.

“Oh, no, I’m going to shoot him with this today and with my gun tomorrow,” I said as I picked up my movie camera.

I was soon sitting on a ridge at the foot of the main mountain talking turkey — hen talk when an old gobbler began to gobble above me. I’m not an expert caller like Samson or Brownie, but I soon had that old gobbler thinking I was the hottest hen he’d ever heard.

I saw a movement just where I thought he would come off. At first I thought it was a deer. Then I detected the outline of a man. Someone else was after Longbeard.

All at once I noticed a black spot in an open place on the mountain. Then it moved. Then, of all things, it glided off the mountain straight toward me and landed less than 75 yards lower down. I had my camera ready before he touched the ground.

Did I shoot? No. The red arrow said it was too dark in the blueberry brush and laurel, so he passed within 15 steps of me as he made his way over the ridge. I still believe that he knew opening day had not yet come.

Was he gone? Well, he was certainly going. He passed down the side of the ridge and each gobble was farther away. Then I started calling again. The little turkey wingbone called, “Come back, come back, you silly old man. I’m the sweetest little hen in this or any thicket, and I let you pass by on purpose. Try again.”

The next gobble was closer. I knew he would come back, so I crawled a little closer to the top of the ridge. If he came over the ridgetop, he would be silhouetted against the sky. It worked, and the light was right. I took a once-in-a-lifetime film of a once-in-a-lifetime bird.

I thought I could see the expression of his big reddish-blue face change when the camera began to purr. He took no chances. Two or three long strides with those big legs took him back into the laurel and out of sight. There he stopped and gobbled about his indecision. He wasn’t sure whether that noise came from an enemy or a fluttering flirt of a foolish young hen.

He gobbled and strutted and quarreled the entire afternoon away on the side of the ridge and in the hollow below. That was what I wanted. I hoped he would still be there the next morning to hear me call, and I believed I could fool him again.

When the first bright streaks announced the coming dawn, I was lying behind a log just a little above the place where Longbeard had mistaken me for a lady love the day before. If I had reasoned right, he would not go back to the main mountain until he had found out for sure about that vanished hen. Sure enough, just as the sun was about to come up, he announced himself.

For once I had guessed him right. He was roosting exactly where I expected. For the first time in our acquaintance, I began to feel guilty. I had studied the old gobbler for two years. Supposedly, I knew all about him. I didn’t then think of the biblical adage, “Pride goeth before a fall.” Even if I had thought of it, I’m sure I would have applied it to the gobbler and not to myself.

Then it was light enough. He should have been coming off the roost. I saw a movement just where I thought he would come off. At first I thought it was a deer. Then I detected the outline of a man. Someone else was after Longbeard. He couldn’t be one of my gang. They all knew where I was and why. I wasn’t about to let a poacher kill what seemed, all at once, to be a friend of mine.

I stalked this man as I would have stalked a stag. I got to within 10 steps of him before I saw who he was. He was Raymond Orndorff, owner of the land adjoining ours, and he was within range of Longbeard. Neither of them knew that I was there. Raymond had every right to be where he was and to shoot his turkey there. We have an agreement whereby he can hunt on our land and we can hunt on his.

He had his gun up. I was sure he was going to end the long relationship between Longbeard and me. I also knew Longbeard was just another gobbler to Raymond. I froze and waited. I had played the game fairly with Longbeard. Now I would be as fair with Raymond. I’d be sport enough to let him kill my big gobbler.

Then Raymond moved just a bit to see better. The instant he moved, I knew who would win. Longbeard left his limb like a shadow, and like an arrow he swiftly glided back to the main mountain from which he had flown the day before.

I had to work the next two days, but I couldn’t keep myself in the office any longer than that. I went out to look for Longbeard. I’m not sure whether I went back to look out for his welfare or for his downfall.

When the sun came up I was still some distance from where I expected Longbeard to be, but then I heard him gobble. Slowly I slipped through the thicket, wondering who would win this time. I stopped to listen. Another gobbler sounded off on another ridge. Which one was Longbeard?

I compared the sounds the two birds made. One was louder and more commanding and seemed to say, “I’m the master of this mountain.” He had to be Longbeard.

I started in his direction, but for some reason and even before I realized I was doing it, I turned toward the other turkey. The mountain would be bigger and better if Longbeard stayed on it. I felt bigger too for having decided in favor of a friend. My feelings for him were growing into something more than admiration. Then too, there was just a chance the turkey I had decided to stalk was Longbeard. If it turned out that way, almost against my will, I would take him.

I tried to make up for my weakness as a caller in other ways. I got slightly above the gobbler with a small rise between us. With the turkey just over the rise, I could go very near. I lay flat on the ground and gave a short, quiet call. It was a hen saying, “Come over the hill to my house.”

I started in his direction, but for some reason and even before I realized I was doing it, I turned toward the other turkey. The mountain would be bigger and better if Longbeard stayed on it.

The change in his gobble told me that he had heard. He gobbled several times. I didn’t answer. He thought I was a hen turkey, and I wasn’t going to talk myself into the truth. Then — there he was — not more than 20 steps from me and to my left. Was he Longbeard after all? I couldn’t really tell in the excitement of that moment. I tried to move the muzzle of my gun in his direction, but he saw it and started to fly. He was too close and too late. I had my gobbler.

Only a man who has taken one understands the thrill of bagging one of these great birds. I am 67 years old and have killed a wild turkey every year since I was 16, mostly gobblers. I have also taken my share of other game, including the Alaska brown bear. But for me, no other thrill equals the climax of a successful wild-turkey hunt. My last is always equal to my first, and each one in between remains unforgettable.

Read Next: ‘The Gobbler Party’ Is One of Charlie Elliott’s Best Turkey Hunts, from the Archives

I soon had the gobbler by the neck, and you can be sure I looked for his beard first. I had one of the biggest and best surprises of my life. He wasn’t Longbeard, and I had not broken my old record. I had, I believe, set a new record. This gobbler had two beards. The editor of the local paper measured each at 10 inches. I know of other wild gobblers that had two beards, but I know of no double beard of that length. If someone does know of a longer double beard, write to OUTDOOR LIFE about it.

I am retired now. My brother Samson and I plan a long stay in Alaska. Most of it will be spent in the wildest part of Brooks Range, where we will study and photograph wildlife. But I suspect that when the turkey season opens in West Virginia, Longbeard and his kind will call loud enough for us both to answer and leave all the game of Alaska for another hunt on the 7-11 Club’s land.

We’ll hunt for Longbeard again. We can make many more mistakes, but as my son Brownie says, “Longbeard can make only one.”

Read the full article here