We trailed the sheep killer that morning with some of the best dogs on earth, a pack brought to north-central Michigan from the mountains of Tennessee. They were great hounds, sure-nosed and bear-wise, and they did their best. But the killer stopped the hunt cold by swimming the Muskegon.

Armed farmers guarded their sheep again that night. And the killer bear exploded a flock a dozen miles away, leaving the sprawling tracks that made him a legend in the Muskegon Valley.

He was as elusive and clever at saving his skin as he was malicious in his killing. In three years he had slaughtered hundreds of sheep, and been seen but once. That time he walked insolently out of the woods in full daylight and in plain sight of an unarmed farmer. Scattering a flock of sheep, he picked the one he wanted, killed it, and carried it off.

“Slippery as a black ghost,” somebody remarked in the general store at Merritt.

The name stuck. He was the Black Ghost the length and breadth of the Muskegon Valley. Half a dozen of the big sheep ranchers offered a reward for his pelt, but nobody knew how to collect it.

Dogs, traps, and all-night vigils over abandoned kills had failed. While the Black Ghost kept the sheep ranchers tearing their hair month after month, I was developing and training a pack of bear dogs of my own. Those Tennessee hounds had turned me into a confirmed bear hunter. We had plenty of black bears in our part of Michigan, and my hunting partner, George Nystrom, and I decided to hunt them as it’s done in the Southern mountains and in certain sections of the West.

The simple truth was that the Ghost was just too much bear for our dogs. As often as they overtook him he beat them off in a running fight, tearing into them with a savage fury they couldn’t stand up to.

By the end of the year we’d developed a pack of dogs that we thought were good enough to tackle the Ghost. Then we let it be known that we’d go to the help of any farmer. Complaints came in faster than we could take care of them, some from as far as 300 miles away. We managed to take outlaw bears off the necks of quite a few farmers, but not the phantom raider we really wanted.

At first we had trouble getting onto his track while it was still fresh.

The Ghost was not only smart but lucky. Then we were called to a kill that was only a few hours old and the hounds took the trail with all stops out. They ran it into the thick swamps along the Muskegon, swam the river, picked up the trail on the far side and were out of hearing in a matter of minutes. Hours later, in the middle of the after noon, they straggled back one by one, an exhausted and dejected pack.’

When the same thing happened three or four times after that, we figured out the reason. The simple truth was that the Ghost was just too much bear for our dogs. As often as they overtook him he beat them off in a running fight, tearing into them with a savage fury they couldn’t stand up to.

That was a challenge that had to be met. We kept at it and he kept sending whipped dogs back to us. It was three years from the day I’d first seen his tracks at the border of a sheep pasture that things came to a head. I had a phone call late one afternoon from Hartley Davis, a local rancher.

“My boys just found a sheep killed last night, Carl. Tracks? Yeah, the Black Ghost.”

It was too late to go after him that day, but at that season there was a good chance he’d strike two nights in a row somewhere in the neighborhood. Hartley promised to check his flock early the next morning. I alerted three or four other ranchers and warned them to do the same thing.

My phone jangled next morning. “He butchered two more of our ewes last night,” one of Hartley’s boys blurted.

By 1 p.m. we had rounded up fifteen determined farmers and were ready to give the Ghost a run he’d remember.

Nystrom and I picked our three best dogs, Banjo, Traze, and Ranger.

Banjo, a big Walker-and-bluetick with a coarse voice, was the fastest of the three. Ranger, half black-and-tan and half Plott, with a tenor bawl as clear and far-carrying as a bugle, would keep close on Banjo’s heels. Traze, black-and-tan with traces of bluetick and redbone, was the oldest and most reliable of the three. We’d use him for a strike dog and if the going turned hard we could count on him to stay with it, no matter what the younger hounds might do.

The bear played his usual canny tricks from the start. He had carried his sheep down from the pasture into a marshy swale, where the dogs hit his scent strong and sure, opening like an organ choir. But their excitement was short-lived. Bear smell hung rank and heavy in the damp grass of the swale, but at the edge of the upland fields it petered out. Even wise old Traze lost it and gave up.

But by that time we had hunted the Ghost long enough to know where to look for him after he left a kill. We put Ranger and Banjo on leash to avoid any false alarms and swung south in a wide circle along the West Branch River.

With the field to himself, Traze was a pretty sure bet. He opened cold in less than an hour, but it was no place for a bear.

“He’s got his signals mixed,” I said flatly.

“Coon in a log,” George agreed.

But when we clawed our way through the cedar tangles for a look my heart skipped a couple beats. A line of bear tracks led across a mud bar at the edge of the river and only one bear in that part of the country could have made ’em. We had the Black Ghost on wet ground now, where the hounds could follow. We slipped the leashes off Banjo and Ranger and they went away like the wind, singing a trail song to make your hair stand on end.

But we had another setback coming.

The dogs trailed the bear out across a dry ridge and the scent faded again. Ranger and Banjo gave up and headed back toward the Muskegon, casting in wide circles. But not Traze. He plodded along at a walk, picking a trace of bear smell off weeds or brush every now and then and chopping out a gruff announcement each time he made a find. Then he too hit a snag.

We had divided the party by time, half of us keeping on after Traze, the rest doubling back to pick up the young dogs.

On the George Boynton ranch Traze left the track. We met him coming back to us, something I had never known him to do before. He had quit at the edge of a freshly plowed field. It didn’t take long to discover why. The field had been plowed that forenoon, but the bear had crossed it before daybreak. No wonder the old dog was baffled.

I led him across the field and.at the far side he made a couple of short casts and picked up a ribbon of bear scent that a pup could have followed. When he swung down into a cedar swamp, bawling steadily, I knew the Black Ghost had some traveling to do.

Traze put him up from his daytime bed and drove him beyond hearing before we could get into the swamp. Aaron Vandenboss and I went in together, and when we heard the dog again he had the bear at bay, a long way ahead.

The swamp was a hellish place to get through. It took us almost an hour to overtake them. A,11 that time Traze chopped and fretted without let up, harassing and fighting the bear in and out of a big windfall, in a tangle so thick a man had to get down on his hands and knees to crawl through.

Then Traze stopped barking as if he had been choked with a noose. There was a sharp yelp of pain, and we heard the bear growl. It was half snarl, half explosive· grunt-and pure poison all the way through.

We were still trying to figure out what had happened when Ranger came tearing unexpectedly through the brush a dozen paces from us. The bear had broken bay by that time and moved on. Ranger picked up the Ghost’s tracks about where Traze had left off, and the swamp rang with his clear bawling. But even reinforced in that fashion, old Traze still wasn’t persuaded to go back for more. He’d had all the bear he wanted for one day. Ranger was running the smoking track by himself, a mile or more ahead, when Traze came to us at a stiff walk, the weariest hound I had ever seen.

It would be dark in another hour, and Aaron and I reluctantly agreed we were whipped. We had one dog worn to the bone, one lost, and the third running the bear. somewhere beyond hearing. We worked our way out of the swamp and found the rest of the party waiting on a road, Nystrom and Banjo among them. He had encountered the dog near the Muskegon in late afternoon. We scattered along the border of the swamp and just at dark Ranger came out to us, unhul’t but worn to a frazzle.

We still hadn’t seen the Black Ghost. But we had come closer to him than at any time in the three years we had hunted him. The dogs had had him at bay, close enough that Vandenboss and I had heard the sounds of the fight.

We were tired and so were the hounds. but it was likely the bear was at least as tired as we were. He had traveled three hours ahead of the two dogs after Traze put him up, fight ing one or the other of them most of that time. The pace had been fast. He was a lot of bear but he wasn’t tough enough to take that much punishment and start off fresh the next morning. Tomorrow, we’d close in. We agreed to meet at the Davis ranch at daybreak.

We knew the bear was fighting them off, driving them back, gaining a brief respite each time. They couldn’t hold him at bay but the two of them had guts enough to stay with him and badger him to a frenzy.

That night the bear did a most amazing thing. Exhausted? He raided two sheep pastures in that same neighborhood, on opposite sides of the West Branch River and a mile apart. He killed one sheep at the first place and two at the second, dragging them into the brush, eating the livers and leaving the rest.

We got the word from a pair of angry and excited farmers on our way to the Davis place that morning. We led the dogs into a thicket where the last sheep had been gutted. Traze put his nose down to the wet grass, let out a long bloody-hungry bellow, and the show was on. Ivan Elenbass slipped the leashes from Ranger and Banjo and the three dogs made the bottoms ring.

For the first time in his long career ahead of hounds, the Black Ghost had allowed himself the luxury of going only a short distance from his kill be fore bedding down for the day. Traze tracked him across a couple of ridges (Banjo and Ranger lost the trail on the high ground and had to be brought back and put on it again) and busted him from his bed. And now the three dogs went stark crazy on the hot track.

The dogs were driving him north, between the Muskegon and the West Branch, at a clip that kept them out of hearing most of the time. We divided our party and sent six or eight hunters around by car to come into the swamp from that direction. The rest of us kept on after the dogs.

The pace proved too fast now for Traze’s tired old legs. He dropped be hind and his insistence on paddling his own canoe cost him his chance. He stuck stubbornly to the track, doing his work the only way he knew, and when he caught up he was too late.

Nobody was close enough to hear Banjo and Ranger when they overtook the bear. But an hour later Elenbass and I heard them coming back south, bawling in broken outbursts.

They’d trail a short distance and quit, trail and quit again. We knew the bear was fighting them off, driving them back, gaining a brief respite each time. They couldn’t hold him at bay but the two of them had guts enough to stay with him and badger him to a frenzy.

It was not Ivan’s and my luck to be in at the showdown. They drove him past only fifty feet in front of us, but in cover so thick we caught no glimpse of either dogs or bear. We could hear the brush crackling and the two hounds snarling and yammering in an almost impenetrable windfall and alder thicket. To our surprise no sound came from the bear. Maybe he was saving his breath.

It fell to Aaron Vandenboss and Wes Thompson to be in the right spot at the right time, a quarter rn.ile farther on.

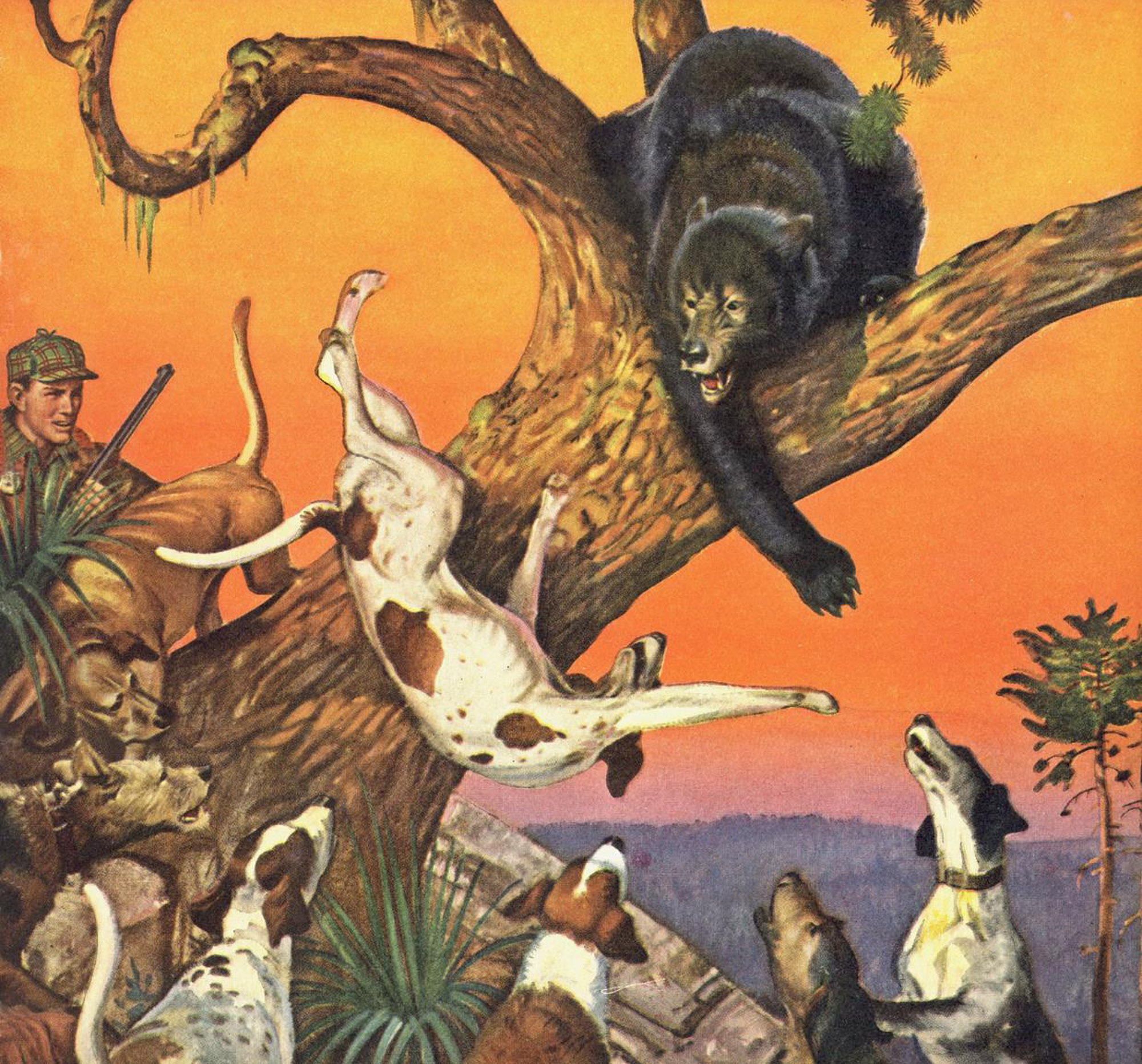

The dogs brought the bear to a halt there, baying him fiercely, Wes and Aaron were only a short distance away when Ranger quit. He ran to them repeatedly, hair erect, look ing for help. They’d sick him on and he’d go back to the fight, but the Ghost was too much for even his Plott heritage and little by little his courage oozed away until he dropped out.

It was Banjo and the bear now, back and forth through the alders, over and under the windfalls, the dog chopping and snarling, the bear growling and popping his teeth in red-eyed rage. The two men were fairly in the thick of it but the cover was so heavy and the hound so close they didn’t dare risk a shot. Half a dozen times Banjo had black fur in his teeth. As often as that happened the bear spun and lunged for him and Aaron and Wes were sure the dog was a goner. But he dodged away each time and came dancing in again. Wes and Aaron had only one rifle be tween them, Thompson’s .348.

Because he had killed other bears on his trap line, Wes passed the gun to Aaron.

“You shoot him,” he whispered. “It’s your first crack at a bear.”

Vandenboss poured in his first shot at a dozen paces when the bear came clear of brush for a second. It smacked the Ghost in the rump. He let go a breath – stopping to roar and slashed at Banjo to avenge his hurt. But the dog eluded him and Aaron got in another shot in about the same spot.

And then, all in a split second, the bear saw the men. He dived head long for the hound once more, missed, changed ends and came smashing at the real cause of his troubles.

Aaron rammed a third bullet into him at just ten yards and he went down in a heap, bawling and screaming. But the 250- grain Silvertip had ripped his heart to a pulp and he was dead in a minute. We got him out of the swamp and hung him in the yard of the Davis ranch late that afternoon. In an hour more than 150 neighbors came for a look at the legendary killer that had harassed their flocks for so long.

Read Next: I Wanted to Hunt Black Bears with My Bow. My Guide Didn’t Trust Me

What sort of bear was this notorious outlaw? Big of course, the biggest any of us had ever seen. But not fat, as we had expected, maybe because of his age. One tusk had rotted away, likely from an injury years before. The other was a yellow stub, worn to the gum. He measured eight feet from nose to tail and dressed out (we did that job in the swamp to make it easier to drag him out) at 378 pounds. We figured his live weight at 500 and an experienced taxidermist who looked him over said he would have weighed better than 600 had he had been as fat as the average black.

He was the most destructive raider in the history of our neighborhood and it had taken us three years to track him down. I don’t think George Nystrom and I have ever been happier over the outcome of a hunt than we were when we drove home with our tired dogs at dark that night.

Read the full article here