During his third Pacific voyage beginning in 1776, Capt. James Cook recorded in his journal: “The universality of tattooing is a curious subject for speculation….”

Today, however, getting inked as a member of the U.S. military is a borderline rite of passage, so much so, writes J.D. Simkins, that the “military culture to tattooing is so prevalent that finding an ink-free service member is infinitely more rare than the alternative.”

But that is a relatively new phenomenon.

The U.S. military — and society’s — embracing and liberalization surrounding the stigma and regulations governing tattoos is thanks, in large part, to the Second World War.

The vast expansion of Naval personnel at the onset of WWII ushered in a new era of the tatted tradition, helped by figures like artist Norman Keith Collins — also known as Sailor Jerry.

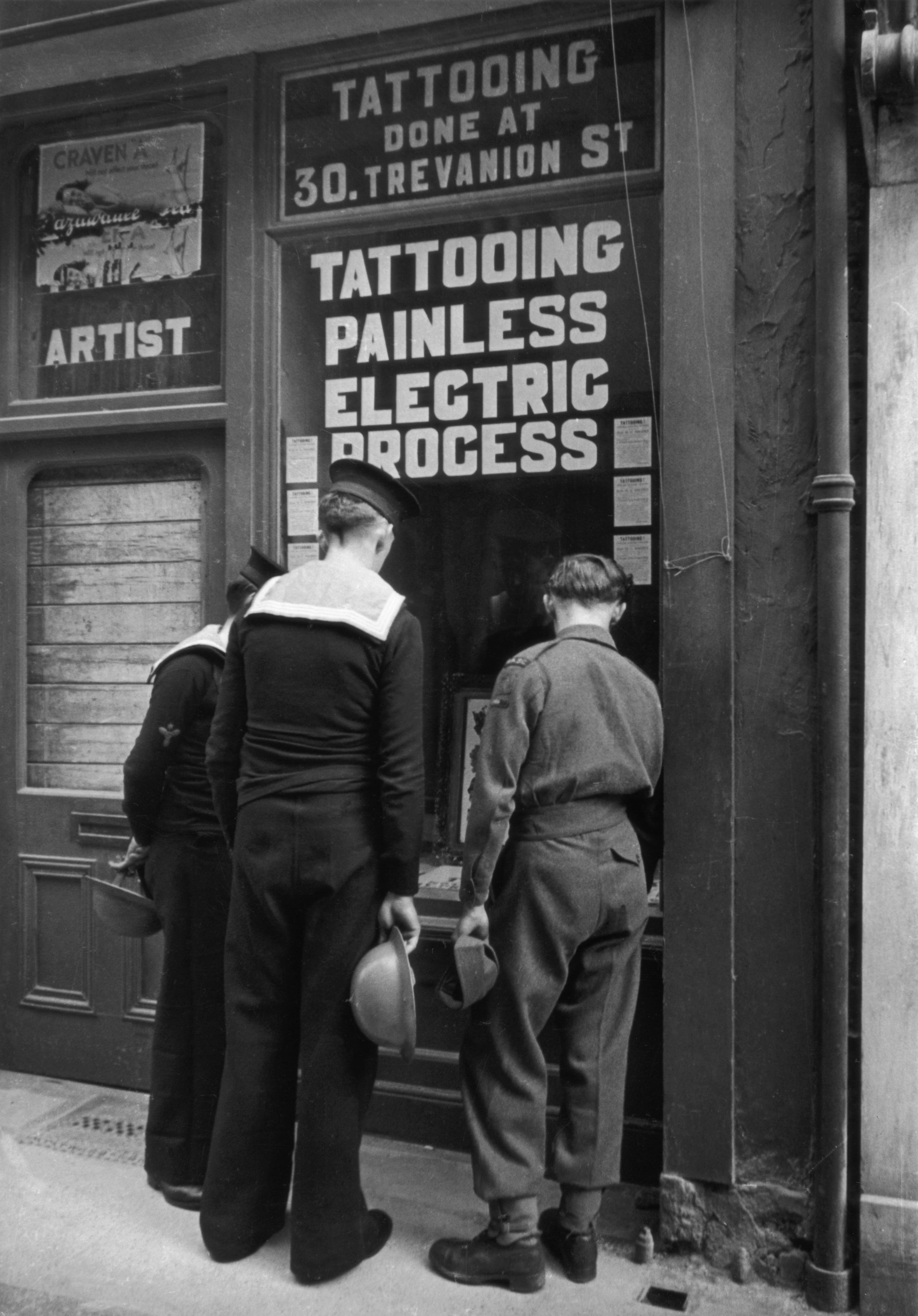

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, soldiers, sailors and new recruits alike lined tattoo parlors to receive their permanent symbols of pride, patriotism — and pinups.

The emergence of tattoos

While Capt. Cook’s Pacific voyages exposed Royal Navy sailors to Polynesian body art, such traditions were practiced in early societies in Europe and Asia, and by indigenous cultures worldwide for thousands of years, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Cook’s exploration of the Pacific, however, did popularize the tradition among his fellow seamen in both Europe and the Americas. So much so that by the 18th century, a third of British and a fifth of American sailors sported at least one tattoo.

During the American Civil War, men in both the Union and Confederate navies often were tatted with military insignia motifs and names of their sweethearts back home. After the March 1862 Battle of the Ironclad — the historic clash between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia — requests for tattoos to commemorate the historic engagement were seen on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line.

By the 1898 Spanish-American War, “Remember the Maine” was a popular choice to be emblazoned on the chests of sailors who were going off to war.

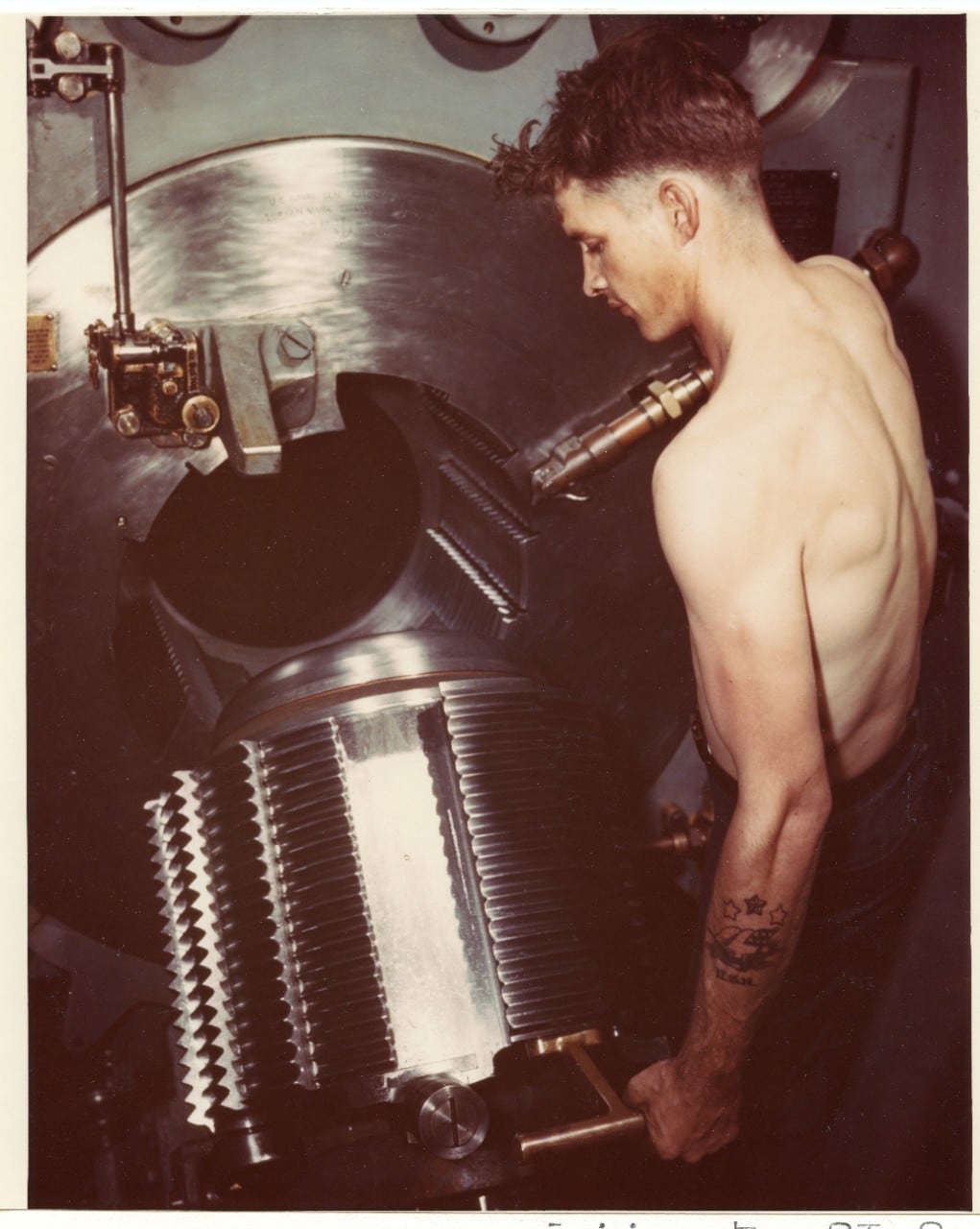

“By this time,” writes Naval Heritage and History Command, “these tattoos had already acquired features recognized today as essential elements of military and patriotic tattoos: the curved scroll with a slogan, name, or date; the stars and stripes; or a giant eagle backdrop — many of them proliferated thanks to the newly invented electric tattoo machine.”

During World War I servicemen were getting their military ID numbers, and later social security numbers, tattooed on their bodies as a means of identification in case they were injured or killed in service. This practice was outright banned during WWII on the grounds that it might give “aid and comfort to the enemy.”

Despite this, body art remained firmly on the fringes of society well into the 20th century.

Tattoos in World War II

After the American declaration of war on Dec. 8, 1941, Honolulu and the port of San Diego became major hubs for men, and occasionally some women, to get inked.

During the war, Honolulu alone boasted eight parlors and 33 operators gaining “the dubious title of the world’s tattoo center,” according to a June 16, 1944, Highland Recorder article.

In particular, 25-year-old Hawaiian native Eugene Miller of “Miller’s Tattooing Emporium” saw his business boom, tattooing over 300 people a day with prices ranging from 25 cents for small pieces to $30 for larger, more intricate art. A large sign above his modest parlor declared him the “world’s greatest and youngest tattoo artist.”

Bert Grimm, known as the “godfather of modern tattoos,” spent over two decades perfecting his craft in St. Louis, Missouri. During the war, the famed tattoo artist — who is rumored to have worked on the infamous Bonnie and Clyde — painstakingly etched symbols of love and belief of God and country onto countless sailors and soldiers waiting to go to battle. But, Grimm noted, the two often sought differing inked motifs.

In 1942, Grimm told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

“The main difference between the soldiers and sailors is that when a sailor comes in to get tattooed, it’s always something with an anchor or a battleship, and the soldiers go more for flags and eagles. I’ve been watching their tastes and drawing new designs to suit them. Oh yes, sweetheart and love designs are going good now, too. […] And here’s a Red Cross Nurse; they lost out in popularity but they are back now.

“The war,” the article continued, “has also been responsible for shortages of tattoo equipment. All the tattoo needles are made in England… Also, although tattoo artists usually don’t mention it to servicemen patrons, most of the darkest and richest tattoo dyes came from Germany.”

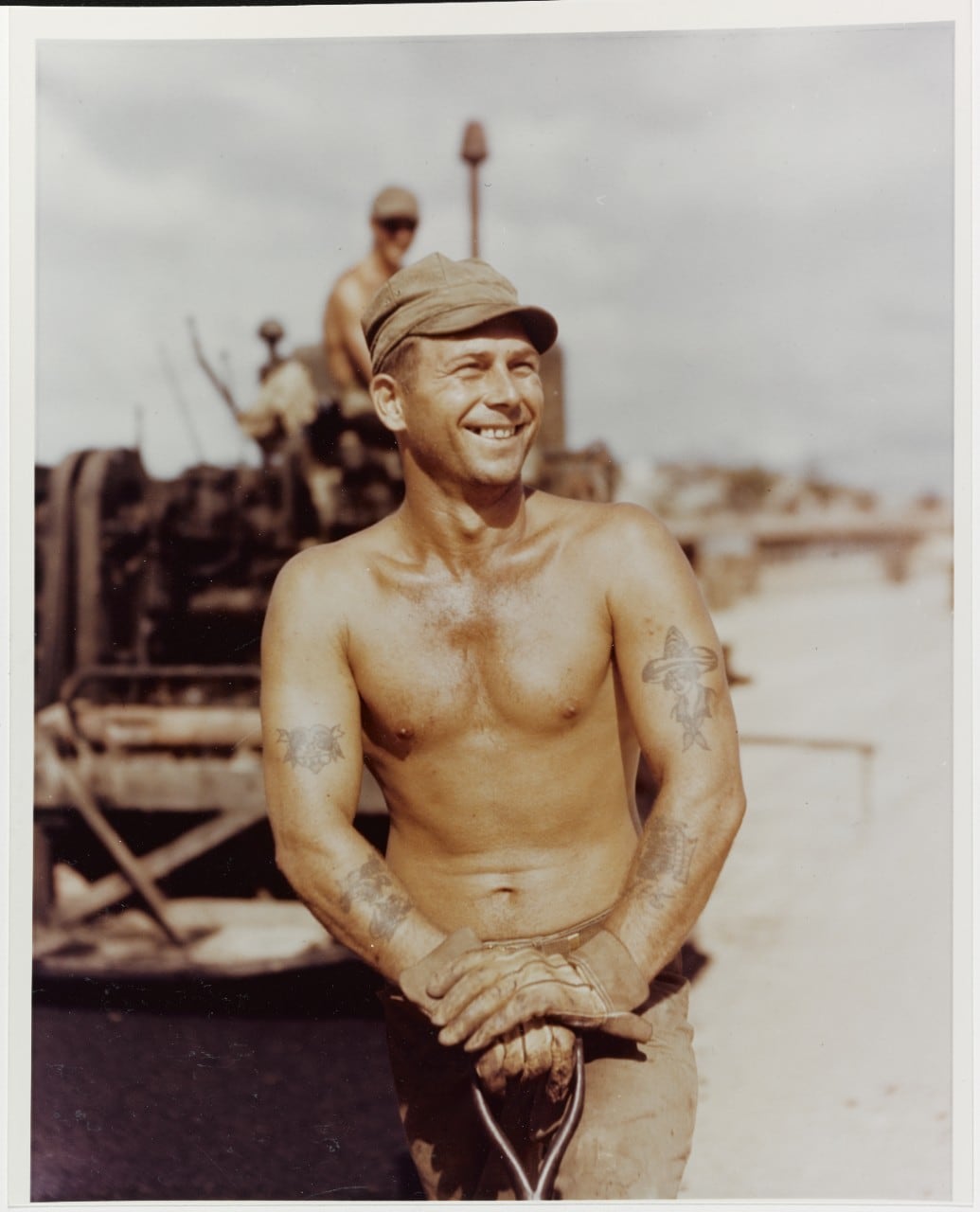

For servicemen willing and perhaps expecting to lose their lives, tattoos were worn as a badge of honor — giving a sense of comradery and, as Danielle Boiardi, the curator of the Lyle Tuttle Tattoo Art Collection, notes in an interview with the Smithsonian, “a permanent mark that they could take with them.”

Since then, the acceptance and proliferation of tattoos has spiked both in America and abroad, with U.S. Navy remaining the least restrictive among U.S. branches of service in terms of body art.

Naval tattoo meanings, per the Naval History and Heritage Command:

Anchor: Originally indicated a mariner who had crossed the Atlantic. In the present day, an anchor in one form or another may be the first nautical tattoo a young sailor acquires (often during his or her first liberty from boot camp) and is essentially an initiation rite into the naval service.

Braided rope/line: Usually placed around left wrist; indicates a deck division seaman.

Chinese/Asian dragon: Symbolizes luck and strength — originated in the pre–World War II Asiatic Fleet and usually indicated service in China. Much later, dragons came to symbolize WESTPAC service in general (also worn embroidered or as patches inside jumper cuffs and on cruise jackets).

Compass rose or nautical star: Worn so that a sailor will always find his/her way back to port.

Crossed anchors: Often placed on the web between left thumb and forefinger; indicate a boatswain’s mate or boatswain (U.S. Navy rating badge).

Crossed ship’s cannon or guns: Signify naval vice merchant service; sometimes in combination with a U.S. Navy–specific or patriotic motif.

Crosses: In many variations — worn as a sign of faith or talisman. When placed on the soles of the feet, crosses were thought to repel sharks.

Dagger piercing a heart: Often combined with the motto “Death Before Dishonor” — symbolizes the end of a relationship due to unfaithfulness.

Full-rigged ship: In commemoration of rounding Cape Horn (antiquated).

Golden Dragon: Indicated crossing the international dateline into the “realm of the golden dragon” (Asia).

“Hold Fast” or “Shipmate”: Tattooed across knuckles of both hands so that the phrases can be read from left to right by someone standing opposite. Originally thought to give a seaman a firm grip on a ship’s rigging.

Hula girl and/or palm tree: On occasion, hula girls would be rendered in a risqué fashion; both tattoos indicated service in Hawaii.

Pig and rooster: This combination — pig on top of the left foot, rooster on top of the right — was thought to prevent drowning. The superstition likely hearkens back to the age of sail, when livestock was carried onboard ships. If a ship was lost, pigs and roosters — in or on their crates — floated free.

Shellback turtle: Indicates that a Sailor has crossed the equator. “Crossing the line” is also indicated by a variety of other themes, such as fancifully rendered geo-coordinates, King Neptune, mermaids, etc.

Ships’ propellers (screws): A more extreme form of Sailors’ body art: One large propeller is tattooed on each buttock (“twin screws”) to keep the bearer afloat and propel him or her back to home and loved ones.

Sombrero: Often shown worn by a girl. May have indicated service on ships home-ported in San Pedro (Terminal Island, Los Angeles) or San Diego prior to World War II, a liberty taken in Tijuana, or participation in interwar Central and South American cruises.

Swallow: Each rendition originally symbolized 5,000 nautical miles underway; swallows were and still are displayed in various poses, often in combination with a U.S. Navy —specific motif or sweetheart’s/spouse’s name.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here