The book had long lingered there. Known, but not acknowledged. Sitting on her father’s bookshelf for decades after the war in Western Europe had culminated in an Allied victory on May 8, 1945.

Except it was no ordinary book. It was Heinrich Himmler’s — one of the chief architects of the Holocaust — personal copy of Adolf Hitler’s Volume I of “Mein Kampf,” replete with Himmler’s own annotations.

It wasn’t until the death of her father, John Fletcher Sisson, who served in the 4th Infantry Division, in 1992 that author and historical preservationist Karen Sisson Marshall recognized what she described to Military Times as the “magnitude of evil” the book possessed.

But what began as a simple process of donating a piece of history forced Marshall to contemplate her own father’s history — and his path to possessing such ephemera.

Can you talk about what occurred after your father’s death in 1992 and what led you down this path?

Two days after my father died, I was asked to go through the files for my mother. As I was going through his files I discovered a 70-page manuscript that had been typed fully, that had been completed and even edited. There was memorabilia, information from World War II and and then this letter that I found with his pictures from the time he returned to Normandy in 1979. He had retraced his own footsteps and he identified on an old map where he thought they had been.

I was shocked when my mother told me she didn’t know anything about any of this. As I said in the book, I felt like I was meeting a man I’d never met. So then, for the first time, I actually paid attention to Himmler’s “Mein Kampf” book. I had always been aware of it, vaguely, but I didn’t realize that he had kept this little book on Himmler with it. I just had never taken anything seriously about his service in World War II. So what we did was we published his manuscript into a small pamphlet and my mother gave it to her close friends and that was it.

But in 2004 for a number of reasons, I decided that I was going to find a home for the “Mein Kampf” volume. My mother came to live with us after dad died, and I realized she was getting older — that was probably the most important impetus. I began to think about this book. I’d gone back to school and gotten a degree in historic preservation and I think I was becoming more aware of the past, its ramifications. So I brought it up to her that I did not want to be responsible for the book if something happened to her.

I tell the story in the book and I shouldn’t laugh, but it was actually very amusing. I was just wandering around, calling people up, telling them that I had Heinrich Himmler’s “Mein Kampf” and I didn’t know what to do with it.

Can you share a little more about the process of deciding what to do with Himmler’s book?

I got my degree and this was, I think, really important. I had gone back to school and I began to think about why I was ignoring my father’s role in history? That’s when I began to look around the house and look at these artifacts and think, “Who was my father?” So the book fell in line with that.

Sotheby’s essentially hung up on me, thinking I was a crank.

And that is how I was treated, sort of like a crank by various places I would call — I probably sounded like one to be fair. You have to remember, we’re in the very beginnings of the internet. That’s where the Baldwin’s [Bookbar comes in. I finally went in because I had bought books from him and he knew I was legitimate. He finally listened to me and he’s the one who found the article on the internet about Volume II. That in turn led us to meet the curator at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York and going through that whole process of learning how you authenticate something.

In your book, “Finding My Father’s Footsteps” you write about two soldiers and two crossed stories. How did you resolve those of Mr. Williams and his father’s, and your own?

I never questioned my father, but the world has to question him. It was then that I received a phone call from Mr. Williams [a pseudonym].

Mr. Williams couldn’t have been nicer. We chatted. I told him my father’s story, and he said, “Mrs. Marshall, with all due respect, I believe your father lied to you.” Just like that. What a gut punch.

His father had told him that at the end of World War II, he was in possession of both volumes — one and two. So he thought my father’s story had to be made up. He seemed to indicate that my father must have, for some reason, decided to take one of the books from his dad, otherwise he couldn’t explain his father’s story.

So in the book I focused my story on resolving my father’s story. I do not want to call into question his father’s story, because I want to respect the fact that soldiers came home and just tell you a little bit of their experience.

In this book you had to work backwards — you had the ending, albeit a confusing one, and to resolve it you had to work back from the beginning. How did you eventually come to resolve the question of your father’s honor?

I wish I could tell you that I was such a good researcher, but I met Bob Babcock, who is the historian for the 4th Infantry Division and he sent me the list of documents they had and I was intrigued by [Swede] Henley’s name. I got copies of different diaries and journals. It wasn’t until I had gone through it that I realized he’d been my father’s commanding officer at the end of the war.

My father’s own journal ended in January [1945], but Henley kept a diary for all of the 11 months that he fought through Europe. So I followed Henley’s diary knowing my father was under him.

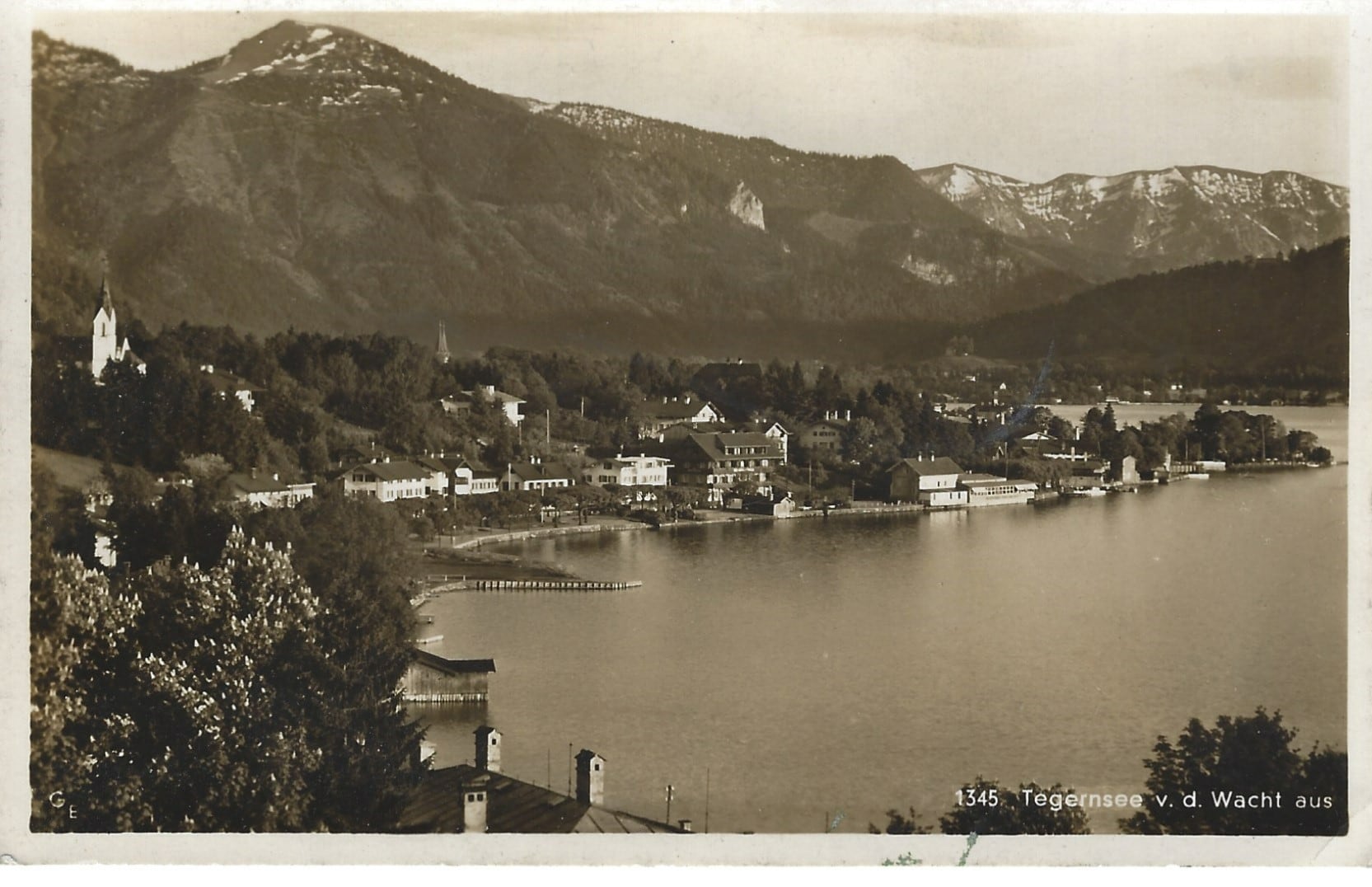

So there it was when Henley put the entry in his diary that they had taken 3,000 prisoners in Tegernsee, [Germany], on May 3. My father’s story always was: “I was the commanding officer in charge of securing Heinrich Himmler’s home.” Somehow my father’s story just came completely alive. He even sent a postcard home to my grandmother from Tegernsee.

So I was like, “Okay, there’s no question in my mind. This is what I think happened.”

The intelligence officer has to file a report, has to report back to their commanding officer and tell them what they’ve done. So I think my father must have been in a report, and I think William’s father saw the report. And so when he said he had both copies, I think that’s what he thought. I think he meant he had Volume II, and that he knew Volume I was in the system.

That’s what I think, but I am surmising.

You write about holding Himmler’s copy of “Mein Kampf” and recognizing the magnitude of evil it possessed. Were there any personal annotations of Himmler’s that stood out to you after it was translated?

I drew a very strong line between Dr. [Richard] Brightman’s expertise on Heinrich Himmler and what our family was doing. I actually don’t know what the annotations are. I did not want explore that side of the book with him.

Can you tell me a little bit about your father, John’s, wartime experience? The 4th Infantry Division had a storied contribution to the Second World War — it was the first U.S. unit to land on Utah Beach, helped to liberate Paris, fought in the grueling battles of the Hurtgen Forest and in the Battle of the Bulge and was among the first units to liberate Dachau. How did researching and following in your father’s footsteps bring about a different understanding of your father?

It changed my life. At that moment when I stood there in Normandy, I reflected back yelling at my father at the dinner table about the Vietnam War. I yelled, “You just don’t understand that people are dying. You don’t care that people are dying. You don’t know anything.”

I knew he had a Nazi bullet — we all knew the story about the bullet that was in his abdomen that didn’t go away. That was sort of a little family joke, you know, that he still had the bullet. I obviously knew somewhere in the back of my foolish 19-year-old brain that my father had been shot at.

I don’t know why I never put two and two together. It wasn’t until I stood there in Normandy that I put the pieces together.

As you mentioned, you were among the protesters of the Vietnam War. How did researching your father’s war experience affirm or alter your opinions on war and its necessity?

What our generation did … it’s just unconscionable what we did. I guess because we were all kids, but we somehow blamed the soldiers who were just kids like us who were sent off to war. We mixed it up. You can stand your ground politically but not conflate the politician’s war with the soldier’s war.

It has been really nice to go to those 22nd Infantry reunions. It’s mainly Vietnam vets now, and we’ve talked and I’m very honest when I sell the book, I always say, “You know, if you’re going to be offended by the fact that I was an anti-war demonstrator, please don’t buy the book.” I’ve had wonderful discussions with these men.

How would you like your book used as a blueprint for others?

At the heart of my book is the idea of how well do we know the stories that impact our lives? What I’m hoping to do is to inspire people to go up in the attic. Get those letters down. Think about someone you love and go learn the story behind the story.

You don’t have to become an expert on World War II, just become an expert on your area. Every war has all kinds of stories to tell — important stories to tell.

World War II called upon an entire generation to do unbelievable things and the vast majority of them rose to the occasion. And we now have these stories buried in our attics.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here