The name of the game was smelt fishing, and my partner — or my opponent, I wasn’t too sure which — was Chris Russell, a travel specialist with Maine’s Department of Economic Development. We were playing the game in a shanty on the ice-bound Eastern River at Dresden, Maine, and I was quickly learning that it is a game of skill rather than chance.

The rules called for us to sit on upended boxes at either end of the shanty in order to tend 19 lines, the lower ends of which plumbed the river’s depths through a trough cut through the floor and the ice below. Somehow I felt like a harpist in a symphony orchestra — that brooding gentleman (or lady) who sits there and stares into space for long periods of time, then finally leans forward on cue and plucks madly at the strings.

But I missed my cue. I’d been sitting for some time, staring at the wall and waiting for my time to “pluck,” when Chris suddenly cried, “You’ve got a bite!”

“Where?” I asked, galvanized into action.

“On number twelve,” he replied. “But he’s gone now. You … Bite on eighteen!”

I plucked line No. 18 and pulled up a bare hook. Then, on my own, I gave No. 10 a yank and pulled up a baited hook. Meanwhile, in a sort of rhythmic arpeggio, Chris had three plump smelt flopping on the shanty floor. With that, the action ended.

“That,” I said, “makes the score three to nothing. Mr. Russell leads, first set.”

“If you want to play it that way,” Chris said smugly. “But this was just a warm-up. The schools won’t really start hitting till later.”

That was good news, I thought, for it would give me a chance to study the rules and get a bit more coaching from the sidelines. I’d already learned something about this sport since following Chris onto the ice that afternoon. And I was destined to learn a lot more before we’d leave the river near midnight.

My course of instruction began with the smelt itself. This is the American smelt, which some people call Osmerus mordax. It is found along the Atlantic Coast from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Virginia.

Writing in 1622, Capt. John Smith, who apparently was more at home with the sword than with the pen, declared, “Of smeltes there is suche abundance that the Salvages doe take them up in the rivers wyth baskets like sives.” There are still quite a few smelt around today.

Greenish-colored on their backs and having silvery sides and darker fins, these fish average eight to 10 inches in length, though specimens a foot long and a pound in weight have been taken.

In winter smelt enter brackish bays and rivers to spawn. From then until spring, when they return to the sea, they are avidly pursued by an army of commercial and sport fishermen armed with hooks and lines, dip nets, and “baskets like sives.”

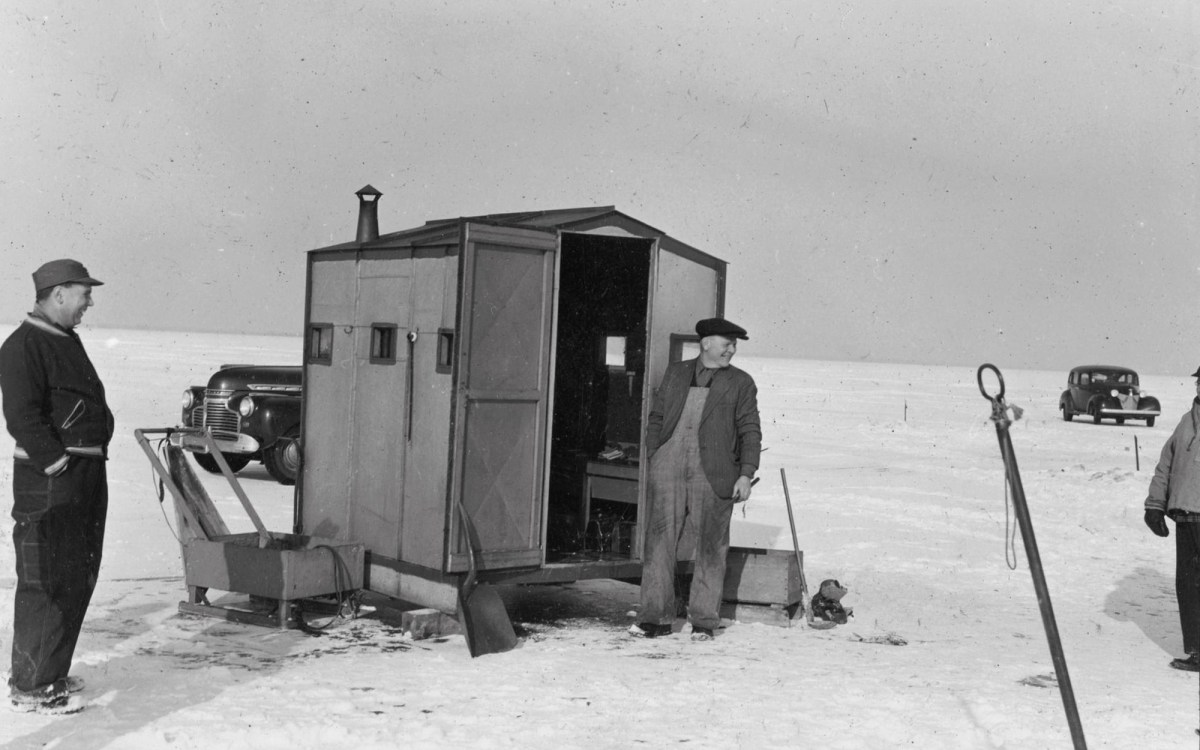

One of the streams these fish ascend in countless millions is the Eastern River, a tributary of the mighty Kennebec in Maine. Here, at Dresden, Chester Burton and Leland Smith have their smelt camps, and it was to this spot that Chris Russell brought me on a cold day in late February.

Three feet of snow covered the ground, and six-foot drifts were heaped over the river’s ice. A precarious road had been plowed down the steep embankment and out along the ice to the smelt shanties, but Chris and I decided to leave our car beside the highway and walk the quarter-mile to the scene of operations. For this we’d be grateful later on.

From where we stood on the high bluff overlooking the river, the shanties looked like a deserted village. There were 48 of them side by side in two rows, and they ranged in color from weathered gray, through yellow and orange, to red. I learned later that the shanties were arranged in rows, rather than scattered about like shad colonies, because this fishing must be done in the main channel of the river.

A few yards back from the river’s edge stood a larger structure, which served as an office. Beside that was a snack shack.

When Chris and I, weighted down with impedimenta, had negotiated the treacherous road to the shanties, we found them locked and empty. But then we saw Leland Smith and the cabin boy, Leon Clancy, trudging toward us over the slippery tidal ice.

“You’re early,” Leland said. “There won’t be much doing till high tide around five.”

“That’s all right,” Chris told him. “We want to look around and take some pictures. And Ted wants to get some dope on the fishing.”

“Well, make yourselves at home,” Leland said. “Chet’ll be along later. We’ll get a fire going, and you can thaw out.”

He led the way into the office, which was cluttered with tools and ice-fishing gear and decorated with pinup art. While Leon went to get more wood, Leland started a fire in the sheet-iron stove and swept a pile of papers from a bench beside it.

“Sit down,” he invited, uncorking a quart-size thermos bottle full of coffee. “What was it you wanted to know?”

I hardly knew where to begin.

“These smelt,” I said. “Do you only catch them at high tide?”

“On the outgoing tide,” he replied. “Fishing’s best for about six or seven hours after high water. River has quite a tide here, and the smelt schools follow it in and out. Right now most of ’em are upstream of us. When the tide ebbs, it forms a big eddy out front of here. The smelt feed as long as the eddy lasts, and then they drop on downriver.”

“How long is the season?”

“In tidal waters such as these it lasts from the time the ice forms in December until it goes out in the spring. We quit the last day of March to be on the safe side because the law says you have to have shanties off the river by ice-out.”

“And what do you use for bait?” I asked.

“Sea worms,” Leland said. Then he really warmed to his subject, and I didn’t have to do any more prompting. Leland digs the worms himself— all year — not only for the local smelt fishing but also for shipment to saltwater fishermen all along the Atlantic Coast.

“I’ve dug up as many as twenty-eight hundred a day,” he said, “and it’s sort of rugged work. In hot weather I dig at night so the worms will keep fresh. I keep them in a big wooden box I haul behind me. With water in it the box weighs around seventy-five pounds, and sometimes I have to lug it across a half-mile of mud flats, sinking up to my knees at each step. It’s sort of rugged … ayah.”

Operating the camps is sort of rugged, too. The big snowstorm of a few days earlier had weighted down the tidal ice so that it sank nine inches. When this happens, as it does frequently, Chet and Leland and Leon have to jack up all 48 camps so that they won’t freeze in and ice won’t cake over their floors.

Then they have to shovel snow from the roofs; plow out the road; bring in supplies, food, and firewood; and repair the damage caused by wind and ice. Some days, Leland declared, the camp stoves burn up over a cord of wood.

“It doesn’t hardly pay fishermen to own their own smelt shanties,” Leland said, “when they can rent one from us for a buck and a half a man, plus bait. That way, they don’t have any headaches.”

“Are the camps rented pretty steadily?” I asked.

He nodded. “They’re usually full, especially on weekends. It’s like a county fair around here. You’ll see later on.”

About then Leon showed up, lugging an armful of firewood, and said, “All set, Leland.”

“O.K.,” said his boss. “I’m giving these boys camp number eleven. Get it rigged up for them.”

I followed Leon and Chris across the rough ice, anxious to see the shanty’s interior. But I had to wait a little while for that. At the door, Leon turned.

“If you gentlemen will just stand back a bit,” he advised, “I’ll have a fire going in a jiffy.”

That turned out to be the understatement of the month. He disappeared inside, and I heard the lid of the sheet-iron stove clang.

I can’t say whether Leon uses kerosene, gasoline, or TNT to start his fires, but the next thing Chris and I knew, Leon was tumbling out of the shanty on the heels of a dull Boom. Simultaneously a great cloud of smoke and flame belched from the shanty’s chimney like a blast from a 175 mm cannon.

Leon’s method works, but I can’t recommend it.

When the roar of flames had died to a steady crackle, Leon let us enter, and I had a chance to inspect my surroundings. Measuring about 8 x 9 feet, the camp contained, besides the stove, a couple of boxes to sit on and a table. Along one entire side, about a foot from the wall, the floor had been cut away. Beneath this rectangular opening, a trench had been sawed through thick river ice, giving access to the tidal currents that rolled and eddied beneath our feet.

There were no windows in the shanty, but illumination was provided by an electric light suspended from the ceiling, and by two other lights covered with tin hoods and placed close to the water at either end of the opening.

“Electricity and running water,” Chris observed approvingly.

What interested me most, though, was the gadget Leon was now rigging. A 2 x 4 ran the length of the wall, about five feet above the open water, and was fastened at either end to projecting, flat boards. These were attached to loosely coiled springs so that the 2 x 4 could be jigged up and down.

Nineteen wooden pegs, spaced about every eight inches, studded the 2 x 4, and around each peg was a coil of line. The business end of each line was fastened to a conical two-ounce sinker, and from the bottom of the sinker hung a six-inch strand of monofilament to which a small hook had been attached. Leon uncoiled these 19 lines one by one, baited each hook with a small piece of sea worm, and lowered them into the water. Then he began adjusting the thin match-size chip of wood tied to each line.

“What’s that for?” I asked.

“Those are indicators,” Leon explained. “When a chip starts to spin, it means you’ve got a bite. You want to set the hook then, but do it gently because smelt have very soft mouths.”

“What about jigging?” Chris asked.

“Yes, you want to jig now and again,” Leon said. “Like this.”

Grasping a short piece of rope tied to one end of the 2 x 4, he gave it a gentle pull. The 2 x 4 dipped, and then the coiled springs lifted it again. Pulling and releasing the rope caused a rhythmic, rocking motion that jigged the 19 lines up and down.

Then I noticed an interesting legend scrawled in pencil on the wall. “January 10, 1965,” it read. “J.W. and T.L. — 73 smelt.” I called my companions’ attention to it.

“That’s nothing,” Leon said, pointing. “Look at that one.”

“February 3, 1967, 135 smelt.”

“When they’re running good,” Leon said, “you could fill the camp with ’em.”

He left us then, and for a time we jigged industriously, inspired by the records on the walls. But nothing happened, so we took some pictures around the camps and bought a couple of sandwiches at the snack bar. Chester Burton drove up in his four-wheel-drive truck, and we chewed the fat with him for a while.

Just at high tide we returned to the shanty, wading now through brackish water that had overflowed onto the ice. It was then that I missed my cue, and it was then that Chris deposited three flopping smelt onto the floor at my feet, as described earlier.

Now, in late afternoon, an air of expectancy overhung the smelt camps as if the curtain were about to rise on the evening’s performance. Fishermen began to arrive. Through the open door of our shanty Chris and I saw them straggling down the icy road from the highway. They came singly, in pairs, and in groups of three or four — men, women, and a few children.

Most of them were afoot, some dragging heaped-up sleds or toboggans behind them, but now and again a group more adventuresome than the rest lurched gingerly along the frozen ruts in their cars. Some of these became stuck, and Chet made several trips in his truck to tow them to the office. Portable radios and six-packs of beer seemed to be standard equipment.

As the cold winter sunset faded, floodlights came on, casting a garish glow on clothing of red and green plaid. A line formed outside the office, where fishermen paid their money and picked up their bait. From there, the crowd trickled away toward the shanties.

The bright lights, the laughter and chatter of voices, the smoke curling from shanty chimneys all gave a bustling, carnival air to the scene.

And then the smelt began to hit. Chris flipped one out on line No. 8 and another on No. 3. I was tending the last nine lines. Suddenly Chris barked, “Number fourteen!”

I grabbed it, and when I set the hook this time I felt a little flurry down in the cold depths. Hauling line rapidly, I flipped a nine-inch smelt up through the opening. But I still hadn’t seen the chip spin.

Then, as I sat watching, the small piece of wood on line 18 moved slightly. I twitched it, felt the brief flurry, and snaked another fat smelt out of the water.

The mystery was solved. Spin was hardly the word to describe the chips’ action. Sometimes they made slow half-turns, at other times they merely vibrated back and forth, and only occasionally did they turn in a full circle. When they moved at all, I discovered, it was time to grab the line and pull.

For the next 10 minutes Chris and I were kept busy hauling lines and re-baiting hooks. Sometimes we had bites on four or five lines at once. In between bites we jigged. We still brought up empty hooks when we grabbed a line too late or tore the barb from a fish’s tender mouth, but when the flurry ended, as suddenly as it had begun, an even dozen smelt lay on the floor.

“Now then,” Chris said, “get out your knife and dress these fish, and I’ll initiate you into another phase of smelting.”

While I gutted our catch, Chris pulled a skillet from his pack and set it atop the hot stove. Into it he sliced about a half-pound of butter, and when the butter was brown and smoking, he laid the fish side by side in the skillet. Ten minutes later he forked them, crisp and brown, from the pan. Peeling each head and backbone away in one piece, he placed the fish between slabs of buttered bread.

Capt. John Smith had a few well-chosen words to say about the eating qualities of Osmerus: “When taken from the fyre and eat, smeltes are of a richness and flavore which is to be compared with no other fishe.”

The captain said a mouthful. When Chris and I finished, only heads and backbones were left.

Turning our attention to the fishing again, we found that most of our hooks had been cleaned while we ate. But no matter – we knew there’d be more smelt along shortly.

And there were. Another short, fast flurry produced a dozen more fish, and I realized now that this was a partnership deal rather than a competitive sport, for we’d long since lost track of our individual scores.

Outside, things were getting into full swing, and I was anxious to see the night life. So, leaving Chris to tend the lines, I went out into the cold and promptly sank through raised shell ice into a foot of frigid tidal water.

Only a few shadowy figures clustered around the office now, but the snack shack was doing a brisk business in hamburgers, hot dogs, and sandwiches. From the shanties rose wreaths of pungent woodsmoke. My ears were beset by the cacophonous blare of radios tuned to different stations, by raucous voices, and by the quavering strains of an enthusiastic trio rendering “Down By The Old Mill Stream.”

I made the rounds of the street of camps, receiving an uninhibited welcome at each one I poked my head into. Their inhabitants made up a sort of United Nations — Irish, French-Canadian, Italian, and Down East Maine — all drawn together by the common bond of smelting. While a cold wind keened outside, they bent over their lines in the warm shanties smelling of mingled woodsmoke, tobacco, steaming wool, and fish.

Most of the fishermen came from nearby Bath, Augusta, Lewiston, and Auburn, Maine, but some were from as far away as New Jersey.

“We come up from Paterson for a few days every year,” a New Jersey party in one camp told me. “We wouldn’t miss it.”

Talk and good spirits flowed freely. The talk ranged widely — from ducks and deer to trout and striped bass, plus the situation in Vietnam and the Red Sox’s chances for the coming season. Opened cans of beer stood on the floor beside the upturned boxes so that, in between jigging and hauling in smelt, thirsty fishermen could take a quick swig.

Fish sputtered in hot fat on some of the stoves, and snacks of popcorn, pretzels, and crackers lay handy on the tables. In most of the camps, smelt littered the floor or reposed in silvery heaps in buckets and baskets.

At each shanty I was offered a can of beer, a shot, or both. This made me think of the old-time pastors who used to make the rounds of their flocks on horseback, enjoying a nip of cherry rum at each stop. Usually, the last parishioner on the list had to boost the parson onto the saddle.

At the last camp I visited, one of the fishermen, in his enthusiasm, stepped into the open water and spread-eagled himself up to his middle in ice water.

“I’m think Hector she’s drop through the hole,” his companion told me gleefully, “an’ someone she’s goin’ to catch him. She’s one big fish, him — no?”

This led the conversation around to the giant sturgeon that occasionally blunder into the smelt lines and make an unholy tangle from one end of the camps to the other. Fortunately no sturgeon showed up that night, but along about 10 o’clock the smelt began to hit in droves.

Watching the boys haul them in one after another sent me back to our camp to get in on some more fishing myself. I found Chris surrounded by silvery fish, and wood chips were twisting all along the trench.

I took my place at the far end of the shanty, and for the next hour we were busy hauling in fish, cutting up worms, and baiting hooks. Sometimes the action slackened off, only to be followed by a blizzard of smelt.

Then, gradually, the flurries became less frequent as the time of low water drew near. One by one the fishermen began to leave. We could hear their footsteps crackling on shell ice, the snorting roar of car motors, and unprintable oaths in French, Italian, and Down East twang as cars became stuck in the ice. Chet did yeoman’s service that night towing stranded vehicles to the highway.

Some diehards, he told us, would stick to the fishing until dawn. But by 11 o’clock most of the camps were deserted, and thin wisps of smoke rose from their dying fires.

Read Next: A Spark Plug, a Paper Clip, and Pliers Helped Me Catch More Lake Trout Through the Ice

By now Chris and I had all the fish we could eat, freeze, and give away, so we reluctantly pulled up our lines and joined the exodus. Chet Burton gave us a ride up to the highway in his truck, and a half-hour later we were back in Augusta.

That was my introduction to smelt fishing, and a different sort of fishing it is.

You can’t say that smelt have the wariness of trout or the fighting qualities of bass, yet there is a unique satisfaction in sitting in a warm shanty on a cold winter night, hauling these tasty little fish up through the ice. It is a satisfaction compounded of warmth, companionship, and plenty of action.

I’ll let Capt. John Smith, who knew whereof he spoke, have the last word: “The catching of smeltes,” declared that redoubtable warrior, “thus affordes bothe entertaynment and riche eat-ynge.”

Read the full article here