This story, “Whitetails Make Mistakes,” appeared in the December 1962 issue of Outdoor Life.

I’VE BEEN HUNTING deer for close to 40 years, and I can count on my fingers the rack-carrying whitetails I have encountered in that time that have made down-right foolish mistakes. Nevertheless, it does happen.

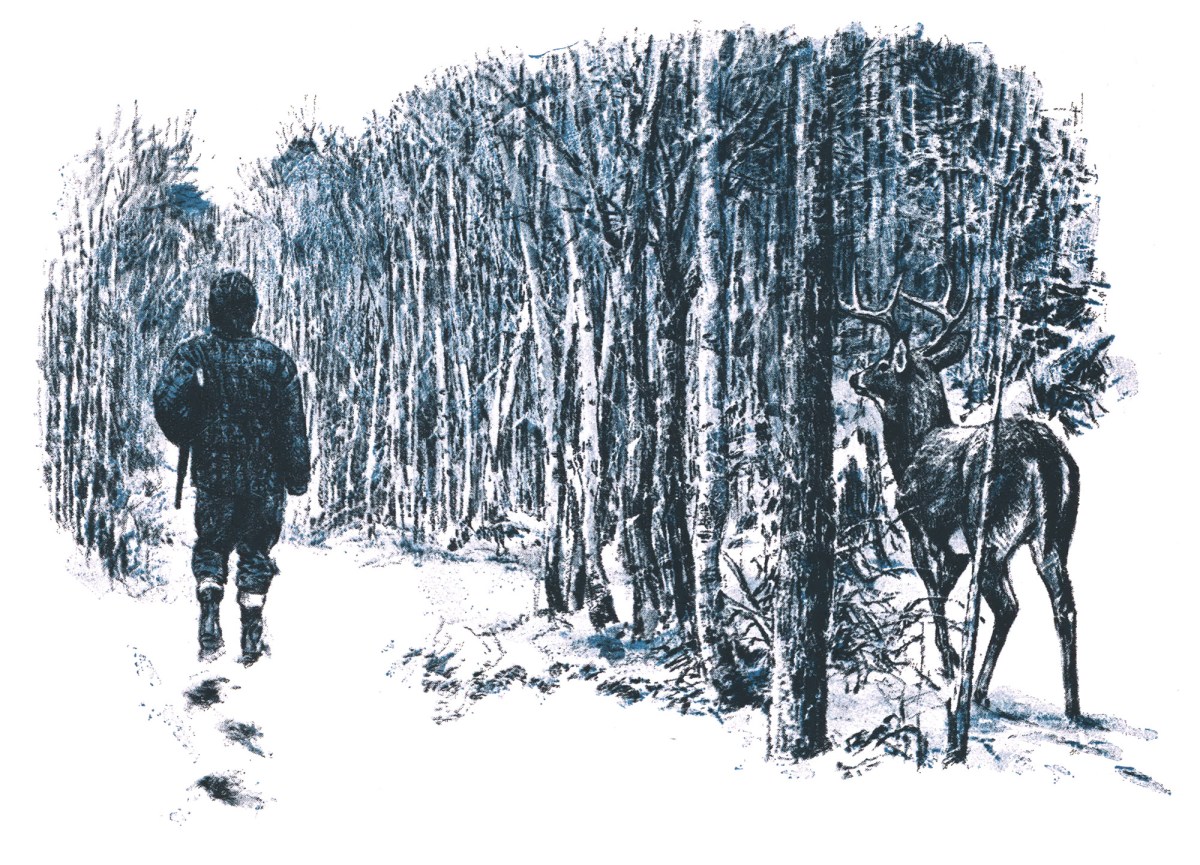

A few falls back, my friend Jess Furbush left his northern Michigan camp one morning in a wet snowstorm and walked out along an old logging road on his way to a stand. Passing through a patch of hardwood, he heard the groaning, creaking sound of two trees rubbing together a few yards to his right. That’s a common noise in the woods, however, and Jess gave it little thought.

As he shuffled along a quarter of a mile farther down the trail, rifle cradled in his left arm and the hood of his parka pulled up over his head, he heard precisely the same sound, again in the woods on his right.

It struck him as queer that there should be two pairs of trees rubbing together so close to the logging road and such a short distance apart. He looked around, and there, only 15 feet away and uttering low, moaning bleats as it walked, was a buck moving through the timber on a course parallel to his own.

Jess stopped abruptly. The deer did the same, and the two of them stood there staring at each other through the falling snow.

Jess reasoned that if he tried to switch the rifle to his right hand, bring it to his shoulder, and turn halfway around for a shot, the deer would be gone before he could kill it.

So instead, he just let the rifle slide into his hands, swung it across in front of him without lifting it more than a few inches, and cut loose a left-handed shot from the hip. The deer went down as if sledged and stayed where it fell. Jess still has trouble getting people to believe the story.

Such behavior is anything but typical, of course. The whitetail buck is one of the wariest and craftiest game animals in the woodlands of North America, superbly equipped, and not much given to making a fool of himself.

He has fairly sharp eyesight, keen hearing, and a nose as good as they come. He’s also smart, with inborn cunning and wisdom gained by hard experience. He takes advantage of the wind and cover, watches where he’s going, keeps an eye on his back track, does his level best to stay out of danger. Cornered in a spot where every avenue of escape is blocked and he must expose himself if he runs, he has the nerve and common sense to lie doggo, head stretched out flat on the ground, not batting an eye. He’ll let a hunter walk past 10 paces away and never move until the coast is clear. Or he’ll sneak out as quietly as a cat on a velvet rug, crouched low and moving like a shadow.

As a youngster, he may be as short on caution as a farmyard calf. It’s a common experience for fawns to walk up and look men over, bursting with curiosity and itching to get acquainted. A hunter I know, sitting on a stump at the edge of thick stuff a couple of falls ago, watched a button buck saunter in, size him up, step closer, and actually sniff at his glove. One sniff was enough. That foolish little deer lit out as if the woods had caught fire, making jumps three times his own length.

Don’t expect older whitetails to behave that way. The buck soon outgrows his fawnhood innocence. If he survives through his second or third fall, he has learned most of what he needs to know, but he’ll go right on getting smarter as long as he lives.

For all his craft and wisdom, however, he’s not infallible, as hunters sometimes are tempted to believe. If he were, venison would be scarce. Fundamentally, every deer hunt is a contest of wits, and there can be only two outcomes. Either the deer or the hunter wins. Usually the loser loses because he did something wrong, and a fair share of the time it’s the deer that goofs. It may not be a big mistake. Not once in a lifetime can you expect a whitetail to shadow you and ask to be killed, as the one did that Jess shot in the snowstorm. But if you are hunting the way you should, a small error on the deer’s part is all it takes to put you ahead.

Whitetail eyesight is only fair where motionless objects are concerned, and apparently deer either don’t see or don’t pay much attention to strange color in the landscape, such as a splotch of red or yellow hunting clothing. But they have eyes like a hawk’s for anything that moves. I’ve come over a ridge, lifted just my cap brim into view on the skyline, and spooked a feeding buck 75 yards away.

All the same, I once gathered in a good buck for no better reason than that he failed to keep his eyes open when he and I were both out for a walk.

It was the first morning of deer season on Beaver Island, off the Michigan mainland in northern Lake Michigan. I picked a stand at the edge of an abandoned farm where deer had been feeding on apples in the old orchard, and the runways showed plenty of use. About an hour after daylight an eight-pointer came out of the brush on the far side of the clearing, too far away for shooting, and trotted 100 yards in plain view. Something had spooked him, for he kept looking back the way he had come. Finally he cut across the upper end of the clearing toward a swamp, still too far away for me to reach. He had almost gained cover when another hunter, whose presence I had known nothing about, piled him up at easy range. I was as surprised as the deer.

The man’s partner came along, and the two of them started to dress the kill. They hadn’t been at it five minutes when a second buck broke out of the swamp and started across the clearing 50 yards from them, going at a hard run. The partner took care of that one in short order. Both deer had made the mistake of exposing themselves in the open in full daylight with hunters in the woods all around them. Maybe the fact that it was the opening morning of the season had something to do with their behavior. Whitetails grow less wary when there’s no shooting.

Anyway, with two bucks killed from the same stand in less than 10 minutes, I decided I’d better move to another spot. I didn’t bother to hunt as I went, for I figured any deer in that neighborhood had been driven out by the shooting. It was a dry, warm morning with a good breeze blowing, and the woods were noisy. Dead leaves crackled underfoot, but I made no effort to be careful.

Yet, before I had walked 300 yards into the timber, I saw something move off to my right. It was a buck moseying along between the trees on a course that would have brought the two of us together in another minute or so. The wind was wrong for him to get my scent, and I suppose he was too far away to hear me walk, but all he needed to do was take one look in my direction to make me out. He didn’t, and I saw him first. I stopped, put the front sight of my rifle on an open place between two tree trunks, and waited for him to walk into it. He never knew what hit him.

A deer’s ears are hard to match. He knows every natural noise in woods and sorts out foreign sounds in a hurry, especially a human voice, even speaking in an undertone. I once watched a buck sneaking off along the border of a swamp ahead of two greenhorns who were conversing in a low mumble. They were 200 yards away, out of sight in thick stuff. The deer, flattened down with his belly almost to the ground and his head low, was keeping the pair located as if he were tracking them by radar. The mistake he made was in ignoring that I might be up on the ridge overlooking his get-away route, which I was.

Sharp as a deer’s hearing is, it lets him down every now and then on one vital score. He fails to locate the source of a sound, even a loud sound close by, and either moves the wrong way or fails to move at all until it’s too late.

Several years ago I was sitting at the side of an old logging road in northern Michigan one morning, watching a runway that came angling out of a steep ravine and crossed about 60 paces to my left. The road wound through open timber, but the runway was partly screened by young hemlocks and I couldn’t see a deer coming up the hill until it stepped into the open.

I had reached the place an hour after daylight. The earth was wet from a night of cold November rain, so I cut an armful of hemlock branches to sit on. I didn’t expect anything to happen right after that for, in gathering the boughs, I had made enough noise by my own reckoning to spook any deer within hearing. Yet within three or four minutes after I had settled down, a deer stepped out of the hemlocks at the spot where the runway crossed the road.

It halted just at the edge of the brush. Michigan had a buck law at the time, and I was carrying a .300 Savage with no scope and couldn’t make out antlers. I did have a pair of 7X binoculars buttoned inside the front of my shirt, however, and when I got them out and leveled, I was looking at a nice eight-pointer.

While I was tucking the glasses back out of the way, he walked across the road, and by the time I was ready to shoot, his head was hidden in thick stuff. I could still see his shoulder and the rest of him back of it, but there was a thicket of young maple whips no bigger than a man’s thumb at the side of the road between me and the deer.

I sized the situation up and took plenty of time. The buck’s hind quarters were in the open, free of brush, but I didn’t want to shoot him there. Only a few times in all my hunting have I had to trail a wounded deer. It’s an unpleasant chore, and to avoid it I like to put my shots ahead of the diaphragm if I can. In this case I decided on the shoulder, despite the fact that it was partly screened by brush. I braced my elbow on my left knee, pulled the gold bead down into the crotch of the rear sight and centered it on a tan patch of deer. I was steady as a rock and as sure of the buck as if he were already hanging on the meat pole back at camp.

The rifle smashed out its sharp report, but nothing else happened. The deer neither fell, flinched, nor moved. I waited a second for him to go down, then racked in another shell and tried again for the same spot.

It’s hard to believe, but I fired three cool, deliberate shots at that buck standing broadside 60 yards away, and they had no more effect than if I’d been shooting blanks.

It wasn’t the fault of the rifle, the sights, or me. Brush deflected my 180-grain bullets three times in a row, and the deer simply stood there, waiting to make sure where the noise was coming from before he moved. It was a disconcerting experience. When I racked the fourth cartridge into the chamber, the clatter of the action finally gave me away. The buck swapped ends and was back in the hemlocks in two lightning jumps, and I threw my fourth shot away as he went out of sight. That was as good an example as I’ve ever heard about of a deer waiting until he is certain in which direction danger lies before he jumps.

One thing deer, even young or reckless ones, can’t tolerate is human scent. Back around 1930 I spent a couple of weeks in midsummer photographing whitetails at a fire lookout’s cabin miles back in the woods on the Tahquamenon River in Michigan’s upper peninsula. There was a sizable clearing around the cabin grown tall with timothy and wild grass, and all through the summer, 30 to 40 deer pastured in that clearing.

It was not in a park or refuge, but for some reason those whitetails were the least wary lot I have ever had anything to do with. The tamest of the herd was an old doe that showed little more respect for a man than for another deer — which wasn’t much.

I took pictures of her until I tired of it. I could walk up within 10 feet of her in the open and without making the slightest effort at stalking or concealing myself. But I had to keep the wind in my favor. Every so often she’d grow suspicious and work around where she could get my scent, and that ended our beautiful friendship every time. The instant she smelled me she’d cut loose with a terrific snort, panic all the others, throw up her flag, run at top speed for 100 feet or so, then stop and look back with a foolish expression on her face as if wondering why she had lost her head. Thirty seconds later she’d be feeding again, but it would take the rest of the bunch at least half an hour to screw up enough courage to work their way cautiously back into the clearing. That old girl wasn’t really afraid of me. She just couldn’t stand the way I smelled.

When a whitetail’s nose tells him there’s a man in the area, he’s almost sure to pay attention. Yet there are exceptions even to that rule. On a hunt in northern Wisconsin one time I encountered a buck that ignored that warning.

He came into sight from an unexpected quarter, 250 yards downwind from my stand. It was too long a shot for iron sights, and although he was moving toward me, I wrote him off, knowing he’d get my scent long before he was within range. But to my surprise he kept coming through thick brush. I caught glimpses of him now and then but had no chance for a good shot until he was about 40 yards off. Then, although he came into the open, he continued walking straight for me. I held my fire to see what would happen.

He couldn’t possibly have failed to smell me, yet he marched up to within 30 feet before he stopped behind some small evergreens and looked over them as if he wanted to play peekaboo. I decided the flirtation had gone far enough.

Over most of his range — and he’s found in just about every state, except Alaska and Hawaii, as well as in Mexico and all through southern Canada — the whitetail is a deer of brush and thickets. He can, however, make out in country with sparse cover if he has to. Whitetail hunting is at least as good in the prairie counties of the Dakotas as in the Black Hills, for example, and Iowa, not a heavily timbered state, yielded 4,000 whitetails to 8,000 hunters in the fall of 1961, a very good average.

In general, though, this deer prefers thick cover. Where it’s available, he stays in it, especially after the shooting starts. Most of the deer killed in the eastern half of the country are dropped in, or not far from the edge of, brush or timber. They rarely venture out into the open in hunting season.

Yet, by way of demonstrating the whitetail weakness for making a fatal mistake now and then, one of the nicest bucks I ever took was shot in the middle of Sleeping Bear dune, a mountain of shifting sand on the shore of Lake Michigan, 30 miles west of Traverse City, Mich.

Except for patches of dune grass and sand cherry, and a few sparse islands of aspen in the wind-scooped hollows, that big dune is as open as a true desert. Five miles long and two wide, it has neither food nor water, and there is no good reason for deer to cross it. Yet they wander all over it, leaving their tracks in the sand through spring, summer, and fall.

Hidden in a thin clump of aspens, a companion and I watched that particular buck come at a walk for half a mile before he got close enough for a shot. The time was around noon, the season was a week old, and the surrounding swamps and timber had been hunted hard. He had no business being there at all. The dune produced three or four good bucks in that same fashion in the two falls I hunted there, when the county was first thrown open to deer hunting around 1940.

What’s the best way for a hunter to cash in on whitetail mistakes? Is there a method of hunting that’s likely to tip the scales in your favor consistently when the deer blunders? There is, and the formula is a simple one: hunt slowly and be alert.

As a matter of fact, any list of deer-hunting rules I ever compile will have that one at the top. It has accounted for most of the venison I have brought home, and most of the chances I have missed were botched because I broke it. I’m not talking here about runway watching. That accounts for a lot of deer and I do my share of it, in small doses, though, since I lack the patience for long periods on a stand, especially in cold weather. When I say hunt slowly, the tip is intended for the hunter who is on the move.

The surest way to score is to take plenty of time. Walk one step and stand still two, an old-timer told me more than 30 years ago. Nobody ever gave me better advice. The more slowly you move the less likely a deer is to see you first. Make frequent stops, and look over every foot of the country ahead before you go on. If you come to the top of a hill or the edge of a clearing, make sure there are no deer in sight before you show yourself. Then wait a little longer on the chance you may have overlooked something. If there’s a whitetail around, let him move first.

You have to give the deer an opportunity to do something wrong. Maybe he’ll be sneaking or running from another hunter and will blunder into you. Maybe he’ll show himself at the edge of a thicket. If he’s bedded down, he may fail to smell or hear you until it’s too late (you’re wasting your time still-hunting unless you watch the wind), or he may wait too long before he slams out. Don’t hurry. Give him a chance to goof.

It pays to watch your back track, too. Deer are likely to leave cover after you have gone past, or wander along behind you by accident. I once killed a nice six-pointer in the Canadian border country of northern Minnesota by waiting at the edge of a swamp after it had been driven and the drivers had moved on. The buck circled around them safely but made the mistake of trying to get back into his home thickets 15 minutes later.

That’s deer hunting. Stop and wait in the right place and you get your chance. Let impatience get the upper hand, walk too fast or move too soon, and the deer wins.

Hunting at a leisurely pace, however, won’t fill the meat pole by itself. It takes alertness as well as patience to do that. Much of the time, especially on bare ground, you have no advance warning of the deer’s presence. He may be standing in brush just ahead, or lying in the top of windfall 20 yards to one side, but you have no way of knowing that. So there’s only one thing to do: hunt every minute as if you expect him behind the next bush, over every rise, at the bottom of each ravine. Maybe he’ll be there, maybe he won’t, but you can’t afford to drop your guard.

Expect the unexpected. Keep your eyes open, your ears cocked. When you stop, don’t just stand. Look and listen, hard. If there’s a wind blowing in puffs, move when it blows, listen when it dies away. And remember that the less commotion you make, the greater the odds in your favor. A walk in the woods for exercise is one thing, a deer hunt is another. The most stupid whitetail you’ll ever meet (and you won’t meet many) can get the best of you if you’re not doing your part.

Not one hunter in 1,000 will ever match the experience two friends of mine had in Minnesota some years ago. Our party arrived in camp a day or two before the season opened, always a good idea, and this pair went out without guns to scout for sign and stands. Following a runway, they saw a huge 12-point buck come around a bend in the trail 50 yards away headed straight for them with his nose to the ground as if he were smelling a doe track.

The men stopped, but the deer came on, taking no notice of them until he was only six or seven paces away. He pulled up short then, stiffened like a dog on point, shook his head, and started to paw the ground like an enraged bull.

He pawed and bluffed for a couple of minutes, showing no fear at all. Then he stood for another minute or two, motionless and rigid, staring angrily at the men. At last he backed off the runway, sneaked sideways a few yards into the brush, and crashed away.

Read Next: I Tracked This Double-Beamed Buck for 8 Miles Across Ohio

That happened during the rut, and deer aren’t always in their right minds then. Don’t look for it to happen to you. Whitetails rarely make such stupid and dangerous blunders.

The canniest of them, though, are guilty of small errors. If you are ready when it happens, even a trifling whitetail mistake can put venison freezer or a rack on your wall.

Read the full article here