This story was originally published in the April 1953 issue of Outdoor Life.

The .30/30 is the most used and the most abused of American big-game cartridges — a centre-fire that’s become an all-time best-seller, like Fanny Farmer’s cookbook. It made its bow almost 60 years ago — in 1895, to be exact — in the Winchester Model 94 rifle. It created a revolution in big-game cartridges compared to which the introduction of such sensational modern jobs as the .270 Winchester and the .220 Swift were but tempests in teapots.

The .30/30 was the first American smokeless-powder cartridge developed solely for big game. It made its appearance at a time when the big old black-powder cartridges were at the peak of their evolution. It vanquished them as speedily as a P-85 jet fighter would destroy a Spad of World War I. It was the father of a whole line of medium-power, medium-range cartridges known as “cartridges of the .30/30 class,” but whereas most of the others are dead and dying, the good old thuttythutty is still going strong.

By 1914 over 700,000 Winchester Model 94 rifles, mostly in .30/30, had been sold, and by 1927 the millionth such rifle was prettied up and presented to President Calvin Coolidge. President Harry S. Truman got No. 1,500,000 in 1948. That’s a whale of a lot of hunting rifles!

In addition, many lever-action .30/30 Marlins have been sold. Likewise a lot of Model 99 Savages. Winchester also turned out some Model 89 single-shots in the caliber, and at one time made Model 54 bolt-action rifles for it. Savage made single-shot .30/30’s on the Model 220 shotgun action. After the last war Savage brought out a light bolt-action Model 340 for said caliber. The cartridge was in considerable favor in Germany for use in the rifle barrel of three-barrel guns or “drillings,” and there it was known as the 7.62 x 51-R. Right after the war I received letters from G.I.’s who had brought back double rifles for it and wanted to know just what it was.

The .30/30, particularly in the little Model 94 Winchester carbine, is the standard cartridge in the far north among Indians, trappers, and Eskimos, and even the smallest of trading posts always carries .30/30 ammunition. It is also a standard cartridge in Mexico, where it is known as the treinta-treinta and was widely used in the Mexican revolution. In back-country Mexico even today there are few ranches where a beat-up old Model 94 carbine is not a cherished possession.

In the years when I was doing a lot of hunting south of the border, I always carried a few boxes of .30/30 ammunition to exchange for guide service, horse hire, frijoles, cheese, and jugs of mescal. Once I traded five .30/30 cartridges for the backstrap of a fat steer as long as your arm and as big around as your thigh.

The .30/30 achieved its popularity because the Model 94 carbine for it was light, short, and handy, but even more because the cartridge was, in contrast with the black-powder cartridges which it replaced, flat-shooting, accurate, and deadly. It came out about the time that Western game was getting scarcer and wilder.

Earlier, close shots had been the rule; now they were the exception. The .30/30 was a 200-yd. deer rifle, whereas the cartridges of the .44/40-.45/70-.38/55 class were, at best, about 125 or 150-yd. killers. It is probable that many of the old black-powder cartridges were a good deal more accurate than the .30/30 in that at any range they would shoot smaller groups, but the .30/30 had more practical accuracy because of its flatter trajectory.

It is fashionable these days to say that the .30/30 has less killing power than the large-caliber black-powder rifles it replaced. You couldn’t tell that to the Western hunters who abandoned their .45/70’s, .44/40’s, and .38/55’s for it. My maternal grandfather killed hundreds of mule deer with Winchester Model 76 and 86 rifles and black-powder cartridges. When he was ranching in northern New Mexico it was routine for him to take a wagonload of deer into the market at Trinidad, Colo., to trade for groceries. He shot grizzlies, black bears, bighorn sheep, and mountain lions. When the .30/30 came out he got one and retired his .45/70. If you had told him that the big black-powder cartridge was superior, he’d have figured you were balmy.

When it first came out the .30/30 was generally known as the .30/30/160, because it had a .30 caliber bullet, a case capacity of 30 gr. of black powder, and its bullet weighed 160 gr. That bullet traveled only at about 1,900 foot seconds muzzle velocity, so you see that the modern loading — 170-gr. bullet at 2,200 — has been considerably beefed up.

The .30/30 is also loaded with a 150-gr. bullet at 2,380, and before the last war it was also loaded with a 110-gr. bullet at 2,720. The 150 and 110-gr. bullets may have been responsible for increased sales, but they were also responsible for a lot of missed bucks. Almost all .30/30 rifles have lever actions which do not lock up the cartridge very tight. They have two-piece stocks and light barrels that are slotted for a rear sight, and vibrate like the dickens. They may do a pretty good job of shooting one, weight of bullet, but a change in bullet weight usually results in a different point of impact.

In addition, most .30/30’s are equipped with open sights that are exceedingly difficult to adjust precisely. Add to this the fact that many .30/30 owners are pretty short on theory and never sight in their muskets, and you’ll see why those bucks got missed.

I had a pal of many years’ standing, an old-time Arizona rancher, who was an excellent catch-as-catch-can shot. One fall, back before the last war, I went out to his place to see if I couldn’t get myself a white-tail and found him in the dumps. His trusted rifle, a Model 94 carbine, had gone to pot, he told me. Fact was, he couldn’t hit a thing with it. He had shot at half a dozen nice bucks so far that season, he told me, and not one had been scratched.

I wasn’t astonished, since I knew the hombre hadn’t cleaned his rifle in years. I decided the poor old thing, after all those years of neglect, had simply given up the ghost. But when I saw a couple of boxes of ammunition loaded with 110-gr. bullets kicking around I began to smell a rat. In spite of my pal’s protests that it was a needless waste of ammunition, I made a target, stuck it up on a tree, and fired three shots.

All were a foot high at 100 yd., even with a fine bead. He also shot, with like results. We drove into the nearest village, got some stuff loaded with 170-gr. soft-point bullets, and the next buck that jumped in front of Old Betsy was a very dead buck indeed. The barrel, through years of neglect, looked like the inside of a smokestack, but she’d still shoot.

Besides that, the lighter bullets at higher velocity do not have more killing power. They cannot be driven fast enough to have an explosive effect at game ranges, and since they do not have the sectional density of the heavier, standard bullet, they do not penetrate so well on the occasional rearend shot.

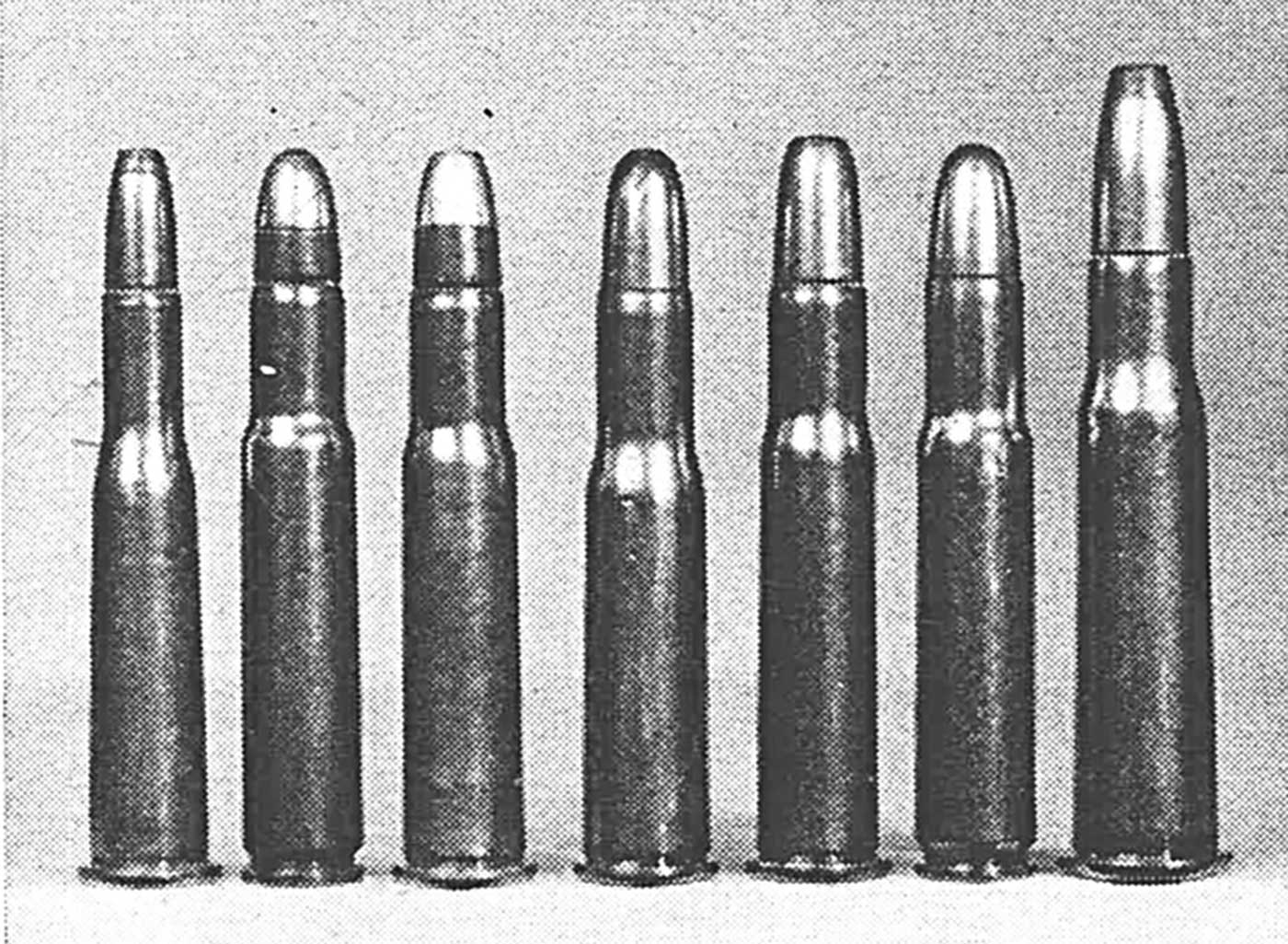

The success of the .30/30 brought about a host of cartridges with similar ballistics. The .33 Winchester, with its 200-gr. bullet at 2,180 foot seconds and muzzle energy of 2,110 foot pounds, is sort of an overgrown .30/30, not greatly more powerful. The .303 Savage, brought out for the Model 99 Savage rifle, uses a heavier bullet ( 190 gr.) at the lower velocity of 1,900. It bears the reputation of being better on heavy game than the .30/30, but I doubt there is actually much difference. The .25/35 W.C.F., with its 117-gr. bullet at 2,280, is simply a little .30/30, and the .32 Special is an offbreed .30/30 with an oversize bullet.

As loaded today, the .32 Special uses a 170-gr. bullet at a velocity of 2,260 and with muzzle energy of 1,930 foot pounds. I have heard arguments about which is the better killer, the .30/30 or the .32 Special. It would take a squad of detectives to find any difference. The only reason that there is such a thing as a .32 Special is that in the early days some customers wanted a cartridge for the Model 94 Winchester carbine that -could be reloaded with black powder.

The .32 Special has a 1-16 twist, the .30/30 a 1-12 twist. A neglected .30/30 will still shoot fairly well, but a .32 Special in similar condition can’t hit a row of barns, since the slow twist will not stabilize the bullet once the rifling begins to go.

The Remington rimless line of cartridges made for the old Model 8 auto rifle and the Model 14 pump were simply rimless versions of the original .30/30 cartridge. The .25 Remington was a rimless .25/35, the .30 Remington a rimless .30/30, and the .32 Remington a rimless .32 Special. All these cartridges are headed for the bone yard, but at one time rifles were made for them not only by Remington but by Standard, (pump and automatic) and by Stevens, (lever-action).

The famous .35 Remington is wholly a Remington design. It is very much alive and has a fine reputation as a sudden killer on deer at moderate ranges.

Strange as it may seem, some .30 Remington rimless cartridges were at one time put out with the head stamp “.30/30 Remington.” They’d fire in a standard .30/30 W.C.F. chamber, all right, but they wouldn’t eject, because they gave a Model 94 extractor nothing to grab. Once a pal of mine leveled down on a buck with one of those cartridges in a .30/30 and wounded it. He finally ran the animal down and roped it so he could finish it off with a pocketknife. This same chap loved to hunt but he was short on theory and to him one cartridge looked about like another. Around 15 years ago he and I were hunting in Mexico and he couldn’t hit a thing with his .30/06. About the third day out I found that all along he’d been shooting my .270 cartridges in his rifle.

But what of the .30/30 as a game cartridge? Is it a killer as some claim, or is it an obsolete wounder as others assert?

My own notion is that it’s a perfectly satisfactory 150-yd. cartridge for animals the size of deer and black bear. I have used the .30/30 and have seen it used for more than 30 years. As long as hits are forward of the diaphragm and the deer isn’t much over 150 yd. away, the .30/30 will usually do a one-shot job. Chances are that the buck won’t fall in his tracks. He may run 25 yd. to 100 yd., but he’s a dead deer.

I do not advise anyone to shoot a buck in the abdomen with any cartridge, but sometimes such a shot cannot be avoided. Hit with a bullet from a rifle of the .30/30 class, a gut-shot deer will often get away, whereas a quick-expanding bullet at high velocity will usually put him down. As a rule he won’t go far. Sometimes he won’t even get up. Many times ( although I never count on it) I have seen gut-shot animals killed instantly with high-velocity bullets.

At the risk of being considered a conservative and a mossback, I am going to hazard a wild-eyed guess that probably the best .30/30 deer bullet is the old-fashioned thin-jacketed soft-point with a good deal of lead exposed at the tip. The average American deer (even a mule deer or one of the larger varieties of northern whitetail) is not a large, brawny, or blocky animal. For sudden kills, the problem is not deep penetration but rapid expansion. Particularly on a broadside shot through the rib cage, a deer does not offer much resistance to the bullet. I’ve shot a good many deer in my day, in the brush and in the open, and I’ve had far more trouble with bullets that failed to open up fast enough than with bullets that didn’t penetrate deeply enough.

The ordinary soft-point bullet mushrooms quickly and strikes a hard and damaging blow, whereas some of the newer bullets with harder cores and stiffer, harder jackets don’t do enough damage to smack a buck down in his tracks. I once saw an antelope hit in the hind end with a fancy 170-gr. .30/30 bullet. It went through him from stern to stem and came out his forehead. He was, of course, a dead antelope; but if he’d been shot through the lungs he’d have run a mile.

Used as it should be used, in the brush and in the open up to about 200 yd., the .30/30 is a satisfactory deer cartridge. It won’t lay a deer down with a poorly placed shot, as will the more powerful .348 Winchester or the .300 Savage; but if the hunter breaks a buck’s neck or gets a bullet into its chest cavity, he’ll have himself a piece of meat.

Used by reckless and careless hunters at long range, it is a very poor deer cartridge. In the Southwest, where I grew up and where I hunted for years, the .30/30 in the hands of poor and reckless shots, shooting at long range across canyons and wide ravines, has probably wounded more deer than all other cartridges put together. Dozens of times I’ve seen a mob of hunters armed with open-sighted .30/30’s blazing away at a bunch of deer across canyons at from 300 to 500 yd., hoping to accomplish by sheer fire power what they could not accomplish by accuracy. Usually such hunters don’t know they’ve hit a deer unless it jumps 10 ft. into the air and collapses with a crash, and they never bother to go and see if they can find blood if one gets away alive. For such long-range shooting one needs higher velocity, flatter trajectory, and better sights.

The .30/30 is a darned poor antelope rifle, because antelope, in my own fairly extensive experience, are shot at longer ranges than any other American game. That’s due to the open character of most antelope country, which makes stalking to close range very difficult.

Queerly enough the .30/30, particularly the light carbine, is a pretty good sheep rifle. Now and then a sheep hunter armed with one may have to pass up a long shot on a good ram. But the broken country which sheep usually inhabit generally gives the rifleman, if he knows his business, a close shot at a standing animal. One of the best sheep hunters I’ve known killed his rams with a .25/35 ! And I could have taken at least three fourths of my own rams with an open-sighted .30/30.

Probably more elk and moose have been killed with .30/30 rifles than with any other, but despite that I consider the .30/30 a poor choice for either animal. In the hands of the average man it simply does not have enough soup to be either humane or efficient. Bullet placement that will spill a deer in a few feet with a .30/30 will let the larger and tougher elk run over a ridge and out of sight.

A good shot and a good stalker who can trail wounded game can successfully hunt almost any game with a .30/30, but the once-a-year hunter who may fire no more than a box of cartridges in 12 months should not attempt such use. Frank Golatas, the noted Stone-sheep guide and outfitter of Dawson Creek, B. C., used a .30/30 for years and killed so many moose with it that moose meat ran out of his ears. He also shot caribou, Stone sheep, and grizzly. Frank told me that he tried to lay a bullet in a moose’s lungs. Then he’d sit down and think things over for 15 or 20 minutes before following it up. He’d find the moose lying down, sneak up on it, and shoot it in the head. Unfortunately most of us are not Frank Golatas on the trail.

Nor is the .30/30 a grizzly rifle. Good men have killed a lot of grizzlies with it, but grizzlies have also chewed up a whole flock of .30/30 users who have got into rhubarbs with them. It’s one thing to shoot a moose with a .30/30, because a moose does not shoot back. It is another thing to take on a grizzly.

It isn’t often that .30/30’s are found in the hands of accuracy nuts, but the .30/30 is a surprisingly accurate cartridge. Once, way back in the late ’20’s or early ’30’s, Winchester made some Model 54 bolt-action rifles in that caliber — a rather sour and unprofitable idea, since .30/30 users are not boltaction aficionados, and bolt-action fans don’t care for the .30/30 cartridge. Nevertheless an amigo of mine had one, and for want of anything better to do, I used to shoot it now and then at a bench rest. It had an old scope on it and it would shoot right along with the best .30/06 rifles.

Apparently all ammunition made today is better than the stuff of 20 years ago. Back in the early ’30’s the average lever-action .30/30 I grouped would shoot into about 5 inches. at 100 yd. The ones I’ve tried recently will shoot into 3 or 3 ½.

A friend of mine shot a scope-mounted .30/30 not long ago and got a 2½-inch group—and that isn’t bad!

But in spite of its relatively good accuracy, the .30/30 is no varmint cartridge. I constantly get letters from citizens who want to shoot woodchucks with .30/30’s. The thought makes my blood run cold. The .30/30 makes too much noise for promiscuous use in settled country. It lacks the flatness of trajectory for hits on small creatures at longish ranges, and the average lever-action rifle is a poor platform for a varmint scope. But the worst thing about the deal is that the heavy bullets at moderate velocity ricochet like the devil. This, coupled with the large report, make the use of a .30/30 on varmints dangerous and annoying. If there is anything that drives a landowner nuts it is to have ricocheting bullets go whining over the cowshed.

Read Next: Jack O’Connor’s Final Word on How to Pick a Deer Rifle

She’s an old-timer, this .30/30, but, there’s life in her yet. Used as she should be used, on deer and deer-size animals at moderate ranges, she’s still a fine and useful cartridge. With suitable bullets, killing power is adequate for deer to 200 yd. or thereabouts. Accuracy is better than most people can hold. Recoil is moderate. Of course, the .30/30 isn’t a gun nut’s rifle, a varmint rifle, a moose rifle, or a reloader’s rifle. Nevertheless it will be with us a long, long time

Read the full article here