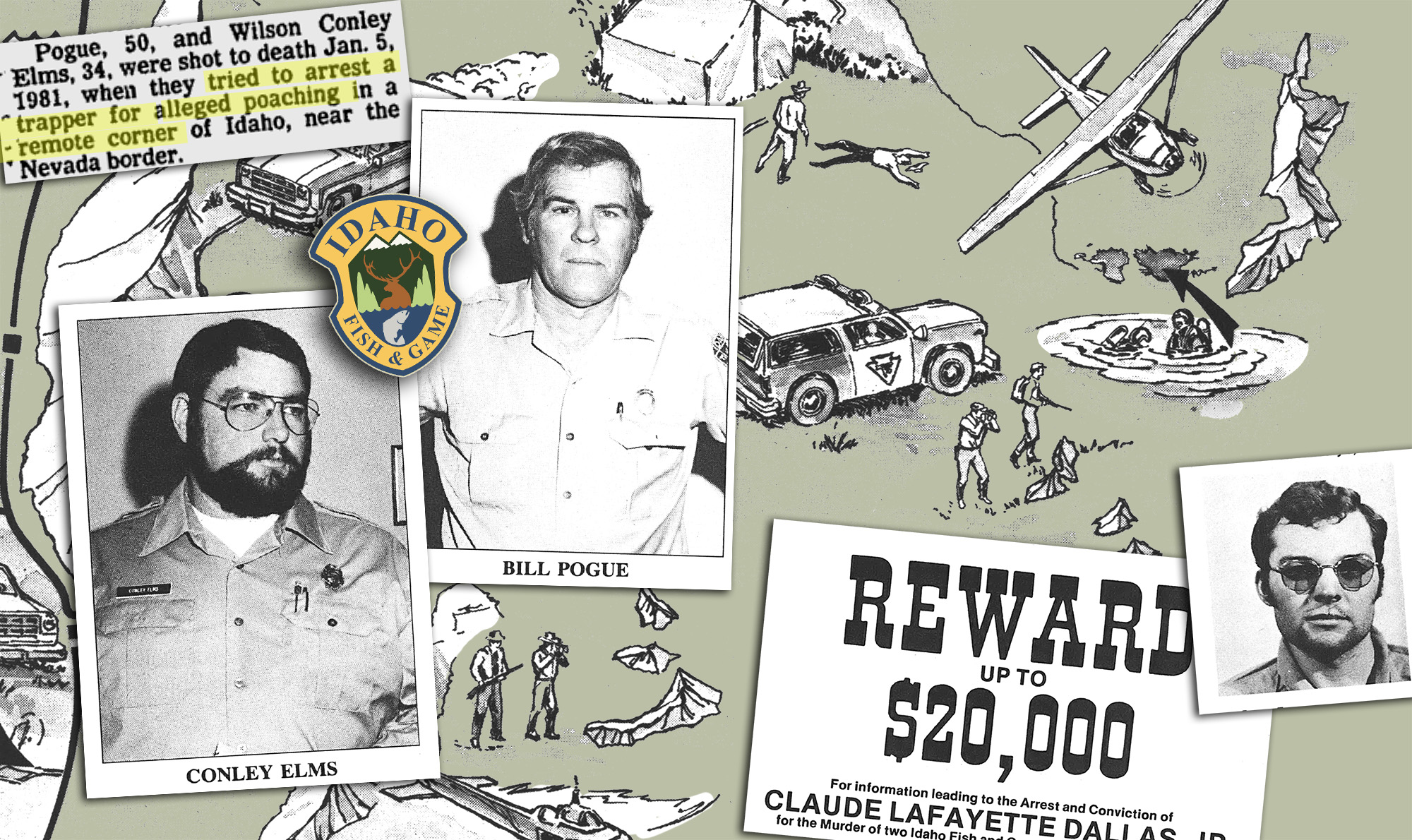

This story, “Last Day of the Wardens,” appeared in the July 1981 issue of Outdoor Life. It was written while Claude Dallas remained at large and game warden William Pogue’s body had not been recovered. This story was published with the following editor’s note:

Editor’s Note: This story was obtained from interviews with various law enforcement officials in Idaho, including state Fish and Game officers, an Idaho Bureau of Investigation agent, and the Owyhee County sheriff. The accounts of the shooting and the events that followed were obtained from the testimony of Jim Stevens, the only witness to the shooting, and others at an Idaho judicial proceeding on February 3, 1981, the purpose of which was to have Bill Pogue declared legally dead. A potato farmer from Winnemucca, Nevada, Stevens has cooperated with enforcement officers, and several poly graph tests indicated he was telling the truth.

It had been a long trip for Idaho conservation officers Bill Pogue and Conley Elms. After a five-hour, 175-mile drive across the rugged desert near the Idaho-Nevada border, the wardens finally parked their pickup at 3 a.m. and crawled into bedrolls. They slept only a few hours on that morning of January 5, 1981. Both rose at dawn to meet with a rancher who had reported illegal trapping.

Nearby, 30-year-old Claude Lafayette Dallas Jr. was camped along the south fork of the Owyhee River. An experienced woodsman, crack shot, and survival expert, he was said to be running 80 traps in the area, mostly for bobcats. A self-styled mountain man, he reportedly took what he wanted from the land without regard to game laws. Dallas was not fond of game wardens. A few years earlier, when arrested in Nevada for a game violation, he’d told law-enforcement officers that he’d never again be taken into custody.

As the morning progressed, Pogue and Elms questioned the rancher. He told them he had ridden into Dallas’ camp on horseback a few days before and had seen bobcat hides and fresh venison hindquarters. Deer season was long past, and the Idaho bobcat season hadn’t opened. Dallas was in a hostile mood, and the rancher sensed his life was in danger, thinking he might be gunned down before he left the camp. The rancher warned the wardens to be extremely careful.

Bill Pogue’s family and friends knew him as a thoughtful, deeply sensitive man, despite his reputation as a gruff, stern, wildlife officer. Conley Elms loved his job as conservation officer and had worked long and hard for the position.

In the meantime, Nevada potato farmer Jim Stevens was making the long overland trip to visit Dallas on that same day. Dallas had worked on his farm. Stevens anticipated spending a few days relaxing and helping with his friend’s chores.

The following account is based on Stevens’ description of what then took place.

Before heading into the Idaho desert, Stevens stopped at the Paradise Bar in Paradise Hill, a tiny Nevada town north of Winnemucca. He picked up Dallas’ mail and supplies from George Nielsen, the bar owner and a close friend of the trapper.

Nielsen lent Stevens a gun and told him to signal Dallas by shooting twice in the air from the top of a hill about three-quarters of a mile from the camp. Upon hearing the shots, Dallas was supposed to hike up the steep trail to help pack supplies to camp.

When Stevens drove to the rim above the camp and fired twice, he heard no answering shots. He decided to walk in with some of the supplies and met Dallas walking up the trail. After they greeted each other, Stevens continued to camp while Dallas went to the vehicle for the rest of the supplies.

Dallas’ camp was a white, lO X 12-foot wall tent about 50 yards from the river. When Stevens reached it, he put the supplies down and went for a walk along the river. Sometime later, he heard voices from the direction of camp, and someone shouted for him to return to the tent. Officers Pogue and Elms were talking with Dallas.

Apparently the wardens had met the trapper on the trail. Or at the vehicle. Pogue had unloaded a handgun that Dallas wore on a belt holster.

When Stevens walked into camp, the wardens unloaded the gun he had borrowed from Nielsen and continued their discussion with Dallas about the reported violations. At that point, one of the officers evidently saw a bobcat hide inside the tent.

Conley Elms entered the tent. “Here are the hides,” he said as he emerged with a bobcat pelt in each hand.

“Well, am I under arrest then?” Dallas asked.

“Yes,” Pogue answered.

Bill Pogue, who had been an Idaho conservation officer for 15 years and before that a police official and game warden in Nevada, was known as a first-class warden, one of Idaho’s best. He was outwardly stern, and had earned the nickname, “ice man with the steely eyes.” A wary man, he always expected trouble. He watched Dallas intently, ready to draw his .357 Magnum at a moment’s notice.

But, despite his training, instincts, and skills, he momentarily took his eyes off the trapper to look at the bobcat hides Elms was holding. Dallas drew a gun.

“Oh no!” Pogue exclaimed, and the next sound was the roar of the gun.

Stevens had been looking away from Dallas, and the blast startled him so badly that he almost jumped into the middle of the shooting. He turned just as Dallas fired a second shot. Pogue fell backward, and there was a cloud of gunsmoke and dust between Dallas and the stricken warden.

Elms had been crouching as he came out the tent. Dallas spun and shot him twice before the warden could reach his revolver. Pogue was still moving and had managed to get his gun out of the holster, but it fell to the ground. Dallas shot Pogue two more times. The·n he went into the tent, came back out with a .22 rifle, and shot each warden once in the temple just.as he would dispatch animals in his traps.

Dallas turned to Stevens. “Sorry I got you in this, buddy,” he said. “You gotta help me.”

Dallas waded across the river to catch two packmules he owned. Unable to catch the bigger mule, be returned with the smaller animal. It weighed little more than 300 pounds. While Dallas was gone, the frightened Stevens had reloaded the gun he’d carried, and he wondered if he’d be the next to die. Later Dallas took the gun and ordered Stevens to help.

The two men loaded Pogue’s body on the mule and packed it up to Steven’s four-wheel-drive. The Fish and Game truck stood nearby.

Conley Elms’ body weighed about 280 pounds. The pair managed to load it on the mule, but the animal balked partly up the mountain and refused to continue. Dallas unloaded the body, used the mule to drag it back down to the river, and dumped the body in.

He and Stevens then destroyed as much evidence as possible. They poured kerosene on blood spots and the wardens’ bloody clothing and burned them.

Then they drove to Paradise Hill with Bill Pogue’s body in the back of the four-wheel-drive. While on the way, they concocted a story to clear Stevens of the incident.

The men pulled up to the Paradise Bar after driving several hours. It was about midnight when they arrived. Dal las knocked on the door of Nielsen’s house and told him what had happened. He also said he wanted to use Nielsen’s pickup truck to dispose of Pogue’s body. Dallas told Stevens to remove his bloody clothing and take a shower. He told Nielsen to burn the clothing.

Dallas filled up the pickup’s gasoline tank, moved Pogue’s body into the truck, and headed out alone into the night. Stevens went home to Winnemucca, and Nielsen stayed at his home. When Dallas returned later, he told Nielsen to take him to a drop-off point. Nielsen drove to a road 12 miles north of Winnemucca, turned west onto another road for two miles, and dropped off Dallas in the desert. The trapper had $100, an olive-drab duffel bag, a backpack, a rifle, and at least one handgun.

Stevens told his wife the false story he had put together with Dallas. His wife thought he was lying and confronted him. The shaken farmer confessed and agreed to go to the authorities with the truth. But before going to the police, he drove to Paradise Hill and told Nielsen he was turning himself in. Nielsen agreed to do the same. Together they told their story to an attorney and a county prosecutor in Winnemucca. No charges were filed against them either in Nevada or Idaho because law enforcement authorities are said to believe that both men acted under coercion and duress. Finally, by the afternoon of January 6, the pieces were fit together.

Since it was almost dark, searchers could do little until morning, but Tim Nettleton, Owyhee County sheriff, had time to fly over the camp area and he saw the Fish and Game truck. By day light the next morning, about 30 hours after Dallas had last been seen, law enforcement officers from several agencies had begun their search. The FBI was involved as well, because Dal las had crossed state borders.

Conley Elms’ body was found in the river that first morning, about a quarter-mile downstream from the camp. But even though the wardens and police widened their search, they found no trace of Bill Pogue’s body or of Claude Dallas.

Officers found the spot where Dallas got out of Nielsen’s truck. The foot prints led into the desert, then turned and came back toward the road, where the trail disappeared. Nevada’s chukar season was still open, and hunters’ tracks were mistaken for Dallas’.

An intensive week-long search failed to turn up Dallas or Pogue’s body. Ed Pogue, brother of the dead warden, vowed to continue the search until his brother’s body is found and Dallas is captured.

“Bill and I were awful close — as close as brothers can be,” Ed Pogue said. “He was my only brother, and you can imagine how I looked up to him. Even after we grew up, we still made it a point to hunt together in Owyhee County.”

Bill Pogue had many other admirers too. The 50-year-old senior conservation officer left behind a wife and four children. His family and friends knew him as a thoughtful, deeply sensitive man, despite his reputation as a gruff, stern, wildlife officer. He was an accomplished artist and enjoyed drawing scenes and persons associated with the outdoors. One of his pieces, which depicted a trapper and a wolf, appeared on the cover of Idaho Wildlife magazine, official publication of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Conley Elms, 34, loved his job as conservation officer and had worked long and hard for the position. A wildlife graduate of Oregon State University, he never gave up trying to get a job as a conservation officer after moving to Boise with his wife Sheryl. He worked odd jobs at an electrical firm, a trailer factory, and with the Ada County assessor’s office. After working part time with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, his dream came true. He was hired as a full-time officer. To make his dream even better, his brother Michael was a conservation officer in nearby Mountain Home, Idaho.

This case is far from closed. As this issue goes to press, Pogue’s body still remains hidden, and Dallas is at large.

Where is Dallas, and how did he escape the dragnet of searchers? No one has the answers. As one authority said, “Dallas could be at all points of the compass.” When I asked Owyhee County Sheriff Tim Nettleton where Claude Dallas might be hiding, the tall, lanky officer took a deep drag off his unfiltered cigarette, shifted his weathered cowboy boots on his desk, and blew a thin stream of blue smoke toward the ceiling.

“Gut feeling?” he asked. “Gut feeling,” I answered.

“First of all,” he said, “you have to understand he is capable of walking a long way over rough country, some 20 to 40 miles a day. My first guess would be he walked or got a ride to California where he’s waiting for spring to break. Then he’ll head for Canada where he spent time traveling in the past.”

This theory has strong possibilities, since Dallas was in the Northwest Territories with his brother recently and remarked he’d like to go back and run traplines.

“Since he learned the fundamentals of Spanish after working with migrant Mexicans on potato farms,” continued the sheriff, “he might have headed south. He told some friends he wanted to go down there some day.

“He also might have headed for the swamps of the Southeast. His folks are in South Carolina, and the swamplands would be right for his style of living.”

Nettleton showed me a map on the wall of his office. A pin was stuck in Paradise Hill. A string tied to the pin evidently had been stretched and rotated many times by frustrated officers as they tried to find Pogue’s body. Because the police knew how many miles Dallas drove in Nielsen’s pickup, they had the radius narrowed to 25 to 30 miles from Paradise Hill. Officers filled the gas tank afterward and determined about 85 miles had been covered, including the 25 miles Nielsen drove. That meant Dallas drove about 60 miles round-trip when he disposed of the body.

When Dallas returned to Paradise Hill, he said he hid the body where no one would ever find it. The region is pocked with countless abandoned mines and shafts, and he apparently found a place so perfectly suited that his boast was right. Despite a well organized, methodical search and the assistance of psychics, Pogue’s body is still hidden. Only Claude Dallas knows where it is.

And how about Claude Lafayette Dallas Jr.? What kind of man is he?

Born in Winchester, Virginia, he reportedly showed up in Nevada about 10 years ago, riding a horse and leading two packmules. Acquaintances say he rode west on horseback from the East. According to Sheriff Nettleton, Dal las was clean and kept a tidy camp. He saw a dentist in Winnemucca regularly and did not smoke or drink. He had the ability to get along with people if he chose to do so. Well-liked in the Neva da farm communities where he worked, he was known to lend money to friends who were down-and-out. “He wasn’t a social recluse, either,” the sheriff said. “He appreciated neons and nylons, if you know what I mean.”

However, Dallas was considered unpredictable and dangerous by those who knew him.

“You don’t dare cross Dallas,” a friend told the sheriff.

Why would Dallas kill the game wardens? Evidently he felt they were imposing on his rights in the outdoors. Sheriff Nettleton explained that in Dal las’ mind, the officers were trespassing in his domain.

Dallas has been formally charged with murder. Nettleton showed me three books discovered in Dallas’ camp. One of them, No Second Place Winner, is about fast draw and fire arms. A passage in the book says: “Be first or be dead — there is no second place winner in a gun fight.” Another book, Kill or be Killed, is described by its publisher in this way: “a book which belongs in every institution charged with the training of police officers or soldiers.” The third book, Firearm Silencers, deals with various silencers used on weapons.

I asked the sheriff if he had any clues to Dallas’ whereabouts.

“Not a thing,” he said. “We get five or six leads daily, and we’ve checked every one out, but none were good. I’m afraid we might be in for a long search, maybe a year or more. Dallas will probably hide out in a big, wild area and he’ll be tough to find. I just hope he doesn’t gun down someone. I’m afraid that’s how we might end up getting on to his trail.”

Nettleton ground his cigarette butt into an ashtray, and for the first time his mood turned harsh.

“I want Claude Dallas,” he said. “I want him bad.” And so do a lot of other people.

Editor’s Note (July 2025) — Claude Dallas remained at large for 15 months, until he was located on April 18, 1982 by FBI agents in Paradise Valley, Nevada. He was confronted fewer than 50 miles north of where he killed Pogue and Elms. Dallas had been living in a trailer and, when he fled in a pickup truck, was pursued with air support and captured. He was shot in the heel during his escape attempt, according to the Spokane Chronicle, and ultimately charged with first-degree murder. Dallas testified during his trial that he acted in self defense. Ultimately he was convicted of two counts of voluntary manslaughter and a firearms charge, and sentenced to serve 30 years in prison. In March 1986 he escaped the Idaho State Penitentiary and remained on the FBI’s Top 10 Most Wanted List for nearly a year before he was recaptured on March 8, 1987 in Riverside, California. He was outside a 7-11 at the time. After serving a total of 22 years, Dallas was released from custody in 2005. William Pogue‘s remains were finally recovered some 17 miles west of the shootout site, at the foot of the Bloody Run mountain range. His family planned to spread his ashes in the Sawtooth National Forest.

Read the full article here